Abstract

Background

Quality of antidepressant treatment remains disturbingly poor. Rates of medication adherence and follow-up contact are especially low in primary care, where most depression treatment begins. Telephone care management programs can address these gaps, but reliance on live contact makes such programs less available, less timely, and more expensive.

Objective

Evaluate the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of a depression care management program delivered by online messaging through an electronic medical record.

Design

Randomized controlled trial comparing usual primary care treatment to primary care supported by online care management

Setting

Nine primary care clinics of an integrated health system in Washington state

Participants

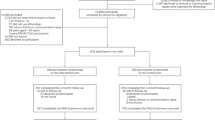

Two hundred and eight patients starting antidepressant treatment for depression.

Intervention

Three online care management contacts with a trained psychiatric nurse. Each contact included a structured assessment (severity of depression, medication adherence, side effects), algorithm-based feedback to the patient and treating physician, and as-needed facilitation of follow-up care. All communication occurred through secure, asynchronous messages within an electronic medical record.

Main Measures

An online survey approximately five months after randomization assessed the primary outcome (depression severity according to the Symptom Checklist scale) and satisfaction with care, a secondary outcome. Additional secondary outcomes (antidepressant adherence and use of health services) were assessed using computerized medical records.

Key Results

Patients offered the program had higher rates of antidepressant adherence (81% continued treatment more than 3 months vs. 61%, p = 0.001), lower Symptom Checklist depression scores after 5 months (0.95 vs. 1.17, p = 0.043), and greater satisfaction with depression treatment (53% “very satisfied” vs. 33%, p = 0.004).

Limitations

The trial was conducted in one integrated health care system with a single care management nurse. Results apply only to patients using online messaging.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that organized follow-up care for depression can be delivered effectively and efficiently through online messaging.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2635–45.

National Committee for Quality Assurance. The state of health care quality 2009. Washington: National Committee for Quality Assurance; 2009.

Olfson M, Marcus SC. National patterns in antidepressant medication treatment. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(8):848–56.

Morrato EH, Libby AM, Orton HD, et al. Frequency of provider contact after FDA advisory on risk of pediatric suicidality with SSRIs. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(1):42–50.

Simon GE, Von Korff M, Rutter CM, Peterson DA. Treatment process and outcomes for managed care patients receiving new antidepressant prescriptions from psychiatrists and primary care physicians. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(4):395–401.

Bower P, Gilbody S, Richards D, Fletcher J, Sutton A. Collaborative care for depression in primary care. Making sense of a complex intervention: systematic review and meta-regression. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:484–93.

Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, Richards D, Sutton AJ. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(21):2314–21.

Williams JW Jr, Gerrity M, Holsinger T, Dobscha S, Gaynes B, Dietrich A. Systematic review of multifaceted interventions to improve depression care. Gen Hosp Psych. 2007;29(2):91–116.

VonKorff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry S, Wagner E. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:1097–102.

Wagner E, Austin B, VonKorff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–44.

Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Tutty S, Operskalski B, Von Korff M. Telephone psychotherapy and telephone care management for primary care patients starting antidepressant treatment: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(8):935–42.

Simon GE, VonKorff M, Rutter C, Wagner E. Randomised trial of monitoring, feedback, and management of care by telephone to improve treatment of depression in primary care. BMJ. 2000;320(7234):550–4.

Wang P, Simon G, Avorn J, et al. Telephone screening, outreach, and care management for depressed workers and impact on clinical and work productivity outcomes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298:1401–11.

Unutzer J, Katon W, Callahan C, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2836–45.

Dietrich A, Oxman T, Williams J, et al. Re-engineering systems for the treatment of depression in primary care: a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2004;329:602–610.

Hunkeler E, Meresman J, Hargreaves W, et al. Efficacy of nurse telehealth care and peer support in augmenting treatment of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:700–8.

Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(20):2099–110.

Richards DA, Lovell K, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression in UK primary care: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 2008;38(2):279–87.

Fortney JC, Pyne JM, Edlund MJ, et al. A randomized trial of telemedicine-based collaborative care for depression. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(8):1086–93.

Liu CF, Fortney J, Vivell S, et al. Time allocation and caseload capacity in telephone depression care management. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13(12):652–60.

Green BB, Cook AJ, Ralston JD, et al. Effectiveness of home blood pressure monitoring, Web communication, and pharmacist care on hypertension control: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299(24):2857–67.

Ralston JD, Hirsch IB, Hoath J, Mullen M, Cheadle A, Goldberg HI. Web-based collaborative care for type 2 diabetes: a pilot randomized trial. Diab Care. 2009;32(2):234–9.

Ralston JD, Rutter CM, Carrell D, Hecht J, Rubanowice D, Simon GE. Patient use of secure electronic messaging within a shared medical record: a cross-sectional study. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(3):349–55.

Derogatis L, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth E, Covi L. The Hopkins symptom checklist: a measure of primary symptom dimensions. In: Pichot P, ed. Psychological measurements in psychopharmacology: problems in psychopharmacology. Basel: Kargerman; 1974:79–110.

Kroenke K, Spitzer R, Williams J. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13.

Spitzer R, Kroenke K, Williams J. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–44.

Krieger N. Overcoming the absence of socioeconomic data in medical records: validation and application of a census-based methodology. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(5):703–10.

Starfield B, Weiner JP, Mumford L, Steinwaches DM. Ambulatory care groups: a categorization of diagnosis for research and management. Health Serv Res. 1991;26:54–74.

Smith A. Home broadband 2010. Washington: Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project; 2010.

Cummings J. The benefits of electronic medical records sound good, but privacy could become a difficult issue. Rochester: Harris Interactive; 2007.

Ralston JD, Coleman K, Reid RJ, Handley MR, Larson EB. Patient experience should be part of meaningful-use criteria. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(4):607–13.

Ralston JD, Martin DP, Anderson ML, et al. Group health cooperative's transformation toward patient-centered access. Med Care Res Rev. 2009;66(6):703–24.

Reid RJ, Coleman K, Johnson EA, et al. The group health medical home at year two: cost savings, higher patient satisfaction, and less burnout for providers. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):835–43.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authorship contributions:

• Study concept and design: Simon, Ralston, Operskalski, Pabiniak, Savarino, Wentzel

• Acquisition of data: Wentzel, Pabiniak, Savarino

• Analysis and interpretation of data: Simon, Ralston, Wentzel

• Drafting of manuscript: Simon

• Critical revision of manuscript for important intellectual content: Ralston, Savarino, Pabiniak, Wentzel, Operskalski

• Statistical analysis: Simon

• Obtained funding: Simon

• Administrative, technical, or material support: Operskalski, Savarino, Pabiniak

• Study supervision: Simon, Operskalski

Financial Interests: Drs. Simon and Ralston are both employees of the Group Health Permanente Medical Group; the remaining authors are all employees of Group Health Cooperative. The authors have no other relevant financial interests to disclose.

Funded by NIMH grant R21 MH082924. The funder had no role in design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Dr. Simon had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Trial Registration

Clinicaltrials.gov ID NCT00755235

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Simon, G.E., Ralston, J.D., Savarino, J. et al. Randomized Trial of Depression Follow-Up Care by Online Messaging. J GEN INTERN MED 26, 698–704 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1679-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1679-8