Abstract

OBJECTIVES: To assess the relative prevalence of subsyndromal depression (SubD) and major depression (MDD) in primary care patients and describe their associated functional impairments, and to define the operating characteristics of a short depression screen (SDS).

SETTING: Three primary care clinics: a university-affiliated Veterans Affairs clinic, a county general internal medicine clinic, and a community health center.

SUBJECTS: Randomly selected adult patients (n=221), aged ≥30 years, with no history of psychiatric comorbidity, current substance abuse, major depressive disorder, chronic pain disorder, or dementia.

MEASUREMENTS: The SDS and the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) were interviewer-administered by an experienced bilingual research assistant to all subjects in the language of their choice. A physician administered independently the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III diagnosis (SCID) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) to all patients who exceeded a minimum threshold on the SDS and to a randomly selected sample of patients who had subthreshold scores. MDD was defined by DSM-III criteria and SubD was defined as two to four DSM-III criteria, of which one had to be depressed mood or anhedonia.

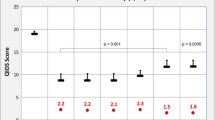

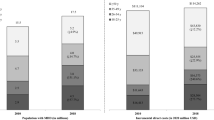

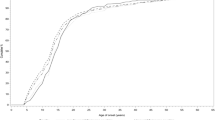

RESULTS: Demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients were: Mexican American 53%, non-Hispanic white 38%, and African American 9%; men 68%; mean age 60±12.7 years; mean level of education 9.5±4.4 years; and hypertension 57%, diabetes mellitus 51%, and arthritis 45%. The prevalences of MDD and SubD (adjusted for sampling strategy) were 4% and 16%, respectively. For the patients who had MDD, the median HDRS score was 17 (interquartile range, 10–18), and for those who had SubD, the median HDRS score was 9 (interquartile range, 8–14). Compared with the patients who did not have depressive symptoms, those who had either MDD or SubD were significantly impaired in multiple domains of self-reported function. The sensitivity and specificity of the SDS for MDD were 100% (95% CI 57–100) and 72% (95% CI 63–81), respectively. For depressive disorders (MDD or SubD), the sensitivity was 66% (95% CI 49–83) and the specificity was 79% (95% CI 69–89).

CONCLUSIONS: SubD was more prevalent than MDD in these primary care settings. Both MDD and SubD were associated with significant functional impairment. The sensitivity of the SDS was lower for identifying depressive disorders (MDD or SubD) than it was for identifying MD.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hoeper EW, Nycz GR, Cleary PD, Regier DA, Goldberg ID. Estimated prevalence of RDC mental disorder in primary medical care. Int J Ment Health. 1979;8:6–15.

Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in Primary Care: Volume 1. Detection and Diagnosis. Clinical Practice Guideline. Number 5 Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, AHCPR Publication No. 93-0550. 1993.

Wells KB, Stewart AL, Hays RD, et al. The functioning and well-being of depressed patients: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:914–9.

Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK. Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA. 1990;264:2524–8.

Zung WWK, Magill M, Moore JT, George DT. Recognition and treatment of depression in a family medicine practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983;44:3–6.

Nielsen A, Williams T. Depression in ambulatory medical patients: prevalence by self-report questionnaire and recognition by non-psychiatric physicians. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1980;37:999–1004.

Pérez-Stable E, Miranda J, Munoz R, Ying Y. Depression in medical outpatients: underrecognition and misdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1083–8.

Andersen S, Harthorn B. The recognition, diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders by primary care physicians. Med Care. 1989;27:869–86.

Zung W. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70.

Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:53–63.

Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, Lum O, Adey FM, Leirer VO. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17:37–49.

Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401.

Koenig HG, Cohen HJ, Blazer DG, Meador KG, Westlund R. A brief depression scale for use in the medically ill. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1992;22:183–95.

Jamison C, Scogin F. Development of an interview-based geriatric depression rating scale. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1992;35:193–204.

Burke WJ, Roccaforte WH, Wengel SP. The short form of the Geriatric Depression Scale: a comparison with the 30-item form. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 1991;4:173–8.

Coulehan JL, Schulberg HC, Block MR. The efficiency of depression questionnaires for case finding in primary medical care. J Gen Intern Med. 1989;4:541–7.

Murphy J. Depression screening instruments: history and issues. In: Attkisson C, Zich J (eds). Depression in Primary Care: Screening and Detection. New York: Routledge. 1990;65–83.

Burnam A, Wells KB, Leake B, Landsverk J. Development of a brief screening instrument for detecting depressive disorders. Med Care. 1988;26:775–89.

Robins L, Helzer J, Coughan J, Ratcliff K. National Institute of Mental Health and Diagnostic Interview Schedule: its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38:381–9.

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:907–13.

Ware JE Jr, Snow K, Kowinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey: Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center, 1993.

Spitzer RL. Williams JBW. Instruction Manual for the Structural Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R Upjohn Version (SCID-UP) “SCID-UP-R3/1/86 Revision”. New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute. 1989.

Williams J. A structured interview guide for the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1988;45:742–7.

Hamilton M. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–96.

Anonymous. The NPAR1WAY Procedure. In: Anonymous (ed). SAS/STAT User’s Guide. Release 6.04. Cary, NC. SAS Institute. 1990:713–26.

Kraemer H. Evaluating Medical Tests: Objective and Quantitative Guidelines. Newbury Park. CA: Sage Publications, 1992:53–7.

Paykel ES, Hollyman JA, Freeling P, Sedgwick P. Predictors of therapeutic benefit from amitriptyline in mild depression: a general practice placebo-controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 1988;14:83–95.

Conte H, Karasu T. A review of treatment studies of minor depression: 1980–1991. Am J Psychother. 1992;16:58–74.

Bohm C, Robinson D, Gammans R, et al. Buspirone therapy in anxious elderly patients: a controlled clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1990;10(suppl):47S-51S.

Guy W, Ban T, Schaffer JD. Differential treatment responsiveness among mildly depressed patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;4:1–2.

Horwath E, Johnson J, Klerman GL, Weissman MM. Depressive symptoms as relative and attributable risk factors for first-onset major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:817–23.

Wells KB, Burnam MA, Rogers W, Hays R, Camp P. The course of depression in adult outpatients: results from the medical outcomes study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:788–94.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Received from the Division of General Internal Medicine, Audie L. Murphy Memorial Veterans Affairs Hospital and the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, Texas.

Supported In part by a Robert Wood Johnson Generalist Physician Faculty Award and the Mexican American Medical Treatment Effectiveness Research Center at UTHSC—San Antonio, Texas. The Center is funded by the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Grant #1-U01-HS07397-02. Dr. Mulrow is a Veterans Affairs Senior Research Career Scientist.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Williams, J.W., Kerber, C.A., Mulrow, C.D. et al. Depressive disorders in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 10, 7–12 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02599568

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02599568