Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We compared the screening performance of different measures of depression: the standard clinical assessment (SCA); the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI); the Center of Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D); and the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire, which assesses diabetes-specific distress. We also studied the ability of these measures to detect diabetes-related distress.

Materials and methods

A total of 376 diabetic patients (37.2% type 1; 23.9% type 2 without insulin treatment, 38.8% type 2 with insulin) completed the BDI and CES-D; patients who screened positive participated in a diagnostic interview, the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Also, all patients completed the PAID questionnaire. Results of the SCA that related to depression diagnosis were reviewed to correct for false negative screening results.

Results

The prevalence of clinical depression was 14.1%, with an additional 18.9% of patients receiving a diagnosis of subclinical depression. Sensitivity for clinical depression in SCA (56%) was moderate, whereas BDI, CES-D and the PAID questionnaire showed satisfactory sensitivity (87, 79 and 81%, respectively). For subclinical depression, the sensitivity of the PAID questionnaire (79%) was sufficient, whereas that of SCA (25%) was poor. All methods showed low sensitivity for the detection of diabetes-specific emotional problems (SCA 19%, CIDI 34%, BDI 60%, CES-D 49%).

Conclusions/interpretation

The screening performance of SCA for clinical and subclinical depression was modest. Additional screening for depression using the PAID or another depression questionnaire seems reasonable. The ability of depression screening measures to identify diabetes-related distress is modest, suggesting that the PAID questionnaire could be useful when screening diabetic patients for both depression and emotional problems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The comorbidity of diabetes and depression is associated with adverse diabetes outcomes. Compared with non-depressed diabetic patients, depressed diabetic patients have poorer glycaemic control [1, 2], a higher risk of multimorbidity and mortality [3, 4], increased functional impairment [5], and poorer adherence to diet, exercise, and diabetes self-management [6, 7]. In addition, coexisting depression has a negative impact on the quality of life of patients with diabetes [8, 9] and is associated with a significant increase in total expenditure on health care [10]. The negative effect of depression in diabetes is not only established for more severe clinical cases of depression, but can also be demonstrated in patients with mild depressive symptoms or subclinical depression [1, 2, 4].

Approximately 30–40% of diabetic patients reported elevated depressive symptoms in self-report measures and 10–15% of diabetic patients suffer from a depressive disorder, according to clinical criteria [11, 12].

The reasons for the high comorbidity of depression and diabetes are not fully understood [13]. Besides general demographic and psychosocial characteristics, certain diabetes-related stressors are associated with elevated depression rates in diabetes; these stressors include the presence of complications, poor glycaemic control, and treatment with insulin [5, 12, 14, 15].

The detrimental consequences of depression in patients with diabetes are not inevitable because effective treatments for depression are available [16–18]. A prerequisite for the effective treatment of depression is the detection of depressed diabetic patients. Indeed, several guidelines for diabetes care [19, 20] recommend screening for depression.

However, experts currently estimate that only 25% of depressed diabetic patients are identified in clinical practice. Thus, timely identification of depressed diabetic patients seems to be a great challenge in routine diabetes care. We therefore investigated the diagnostic performance of different assessment methods of depression in clinical practice: the standard clinical assessment (SCA); depression questionnaires; and the Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire, which is used to assess diabetes-specific stressors.

In addition to the assessment of depression, it seems reasonable to measure diabetes-specific emotional distress in clinical practice. Among patients with diabetes, diabetes-related stressors (e.g. acute and late complications or poor glycaemic control) are known risk factors for depression as well as for reduced quality of life [12, 15, 21, 22]. Furthermore, in previous research diabetes-specific emotional distress was negatively associated with effectiveness of diabetes self-management and glycaemic control while controlling for the effect of diabetes-non-specific emotional distress, such as depression [7]. Thus, in addition to detecting depression proper, it seems reasonable to seek to identify patients with a large number of diabetes-specific stressors [7, 21–24].

Given the relevance of the diagnosis of depression in diabetic patients and the assumed strong desire of clinical practitioners to avoid multiple testing, we also examined the ability of the depression measurement tools mentioned above to identify patients with a high amount of diabetes-related distress, as measured by the PAID questionnaire.

Subjects and methods

Study protocol

All diabetic patients referred to the Diabetes Centre Mergentheim participated in a thorough clinical examination at the time of admission to the hospital. This examination consisted of a thorough interview about the patient’s medical history and current symptoms; laboratory tests; a medical examination; and a review of previous medical reports about comorbidities of diabetes. Based on the results of this standard clinical examination (SCA), diagnoses were given according to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10). The SCA was conducted by a medical doctor and lasted approximately 45 min.

Independently of the results of this SCA, all patients who were admitted for inpatient treatment in June and July 2002 and were aged between 18 and 75 years were invited to participate additionally in depression screening (n=529). Of these patients, 420 (79.4%) gave written, informed consent to participation in the study and completed two depression questionnaires: the German versions of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) [25], and the Center of Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) [26]. They also completed a questionnaire relating to their demographic and medical characteristics. Patients who screened positive in one or both of these screening questionnaires (cut-off score >10 in BDI or >23 in CES-D) were invited to a diagnostic interview. The diagnostic interview chosen was the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The psychometric properties of the CIDI have been studied extensively and are highly accepted [27]. Each CIDI was conducted by a psychology graduate, who was trained before conducting the interviews and supervised during the data collection by a certified clinical psychologist who was not involved in the study. To reduce expectation bias [28], the interviewer was not aware of the test scores in the depression questionnaires or the results of the SCA. According to the ICD-10 criteria, affective disorders were diagnoses F30–F39. Complete depression data were obtained from 388 diabetic patients (74.3%), since 32 of the patients screened positive did not participate in the CIDI. The recruitment and reasons for not participating in the second stage of the study are described elsewhere in more detail [15].

All 388 patients were asked to complete the German version of the PAID questionnaire, which is designed to identify negative emotional responses related to various aspects of diabetes. The questionnaire consists of 20 items (Table 2). Each item can be rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no problem) to 4 (serious problem). According to the recommendation of the measure’s authors, the PAID questionnaire scores are transformed to a scale of 0–100, higher scores indicating more serious emotional problems. The original scale has proved its validity and reliability [7]. The German version of this scale was re-evaluated and showed a highly satisfactory reliability (Cronbach’s α=0.93; Spearman Brown r tt=0.93, retest reliability r tt=0.75); it also has proven construct and concurrent validity [29]. PAID questionnaires could not be obtained from 12 patients; therefore, these subjects had to be excluded from the analysis. Thus, 376 diabetic patients were included in the final analysis (Table 1).

For the diagnosis of diabetes-related stress, a cut-off of ≥40 in the PAID questionnaire was selected to determine whether more severe diabetes-specific emotional problems were present. This cut-off score is based on a series of studies using the PAID questionnaire in European samples of diabetic patients; a cut-off score of 40 is one standard deviation above the mean of the studied population [21, 30].

The two-stage procedure chosen—consisting of a screening procedure using depression questionnaires and the verification of depression using the CIDI only in patients who screened positive—could be affected by so-called verification or work-up bias. Thus, true positive cases with false negative screening results could not be detected [28]. To minimise this bias we checked the records of SCA at the time of each patient’s admission to the hospital; we specifically monitored whether diagnoses F30–F39 were given. Thus, we were able to identify possible false negative results among the negative screened patients and to determine the rate of detection of depression by the SCA procedure.

The study was conducted according to the recommendations of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee.

Statistical analysis

In order to identify the PAID questionnaire items that discriminate best between depressed and non-depressed patients, univariate ANOVAs were performed with several categories of depression status as the independent variables. No depression defined as a low or normal was depression score. Subclinical depression was defined as an elevated depression score, but not sufficiently elevated to meet the criteria for clinical depression. Clinical depression was defined in accordance with the ICD-10.

To determine the screening performance of the PAID questionnaire in identifying patients with clinical or subclinical depression and to identify optimal cut-off scores, receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC) analysis was used. The AUC was calculated to quantify screening ability. The AUC of the screening instrument is evaluated by comparison with the AUC of the diagonal line, which represents classification by chance (AUC=0.50).

The optimal cut-off score of the screening instrument is selected by using the score that is closest to the intersection of the ROC and the diagonal line from the upper left to the lower right side of the graph. This crossing point is usually used to locate the score and provides the optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity [31].

Systat 10.2 (Systat Software, Point Richmond, CA, USA) and SPSS 11.5 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) were used to carry out the statistical analyses.

Results

Depression scores in the BDI or CES-D were elevated in 120 diabetic patients (31.9%). These patients participated in the CIDI, and 49 of them fulfilled the criteria for clinical depression according to ICD-10. Subclinical depression, as defined above, was present in 71 diabetic patients (18.9%). In order to minimise verification bias, the records of the SCA were reviewed for diagnoses F30–F39. A total of 30 patients received a diagnosis of clinical depression based on the results of the SCA. From these, 26 cases were identified through the CIDI. Evidently, four patients with clinical depression received a false negative screening result. Of these four patients, two were treated concurrently with antidepressive medication, and the other two received psychotherapeutic treatment. In these four patients depressive symptoms were concurrently in remission, indicated by negative screening results in the BDI and CES-D. In total, 53 diabetic patients received a diagnosis of clinical depression, indicating a prevalence of clinical depression in this sample of 14.1%. Characteristics of the sample regarding sociodemographic and medical variables are given in Table 1. With the exception of the depression and PAID questionnaires, only sex showed a significant difference among the three subgroups (no or low depression, subclinical depression, and clinical depression).

The results of the assessment of diabetes-related distress are reported in Table 2. In the PAID questionnaire, the items describing worries about future complications and hypoglycaemic reactions and feelings of guilt for suboptimal diabetes self-management scored highest. There were 116/376 (30.8%) diabetic patients who scored 40 or higher on the PAID questionnaire, indicating a great amount of diabetes-related distress in one-third of the sample. There was a significant association (p<0.001) between depression status and diabetes-related distress (proportion of patients with high diabetes-related distress: in patients with low or no depression it was 37/252 [14.7%]; in patients with subclinical depression it was 40/71 [56.3%]; and in patients with clinical depression it was 39/53 [73.6%]).

Before we compared the diagnostic performance of different methods for assessing depression, we examined the screening performance of the PAID questionnaire for depression. To explore the ability of the PAID questionnaire items to discriminate among the different states of depression, univariate ANOVAs with depression status as the independent variable (no or few depressive symptoms vs subclinical depression vs clinical depression) were calculated for each of the PAID questionnaire items. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 2. All PAID questionnaire items were able to discriminate significantly among the different states of depression. Cognitive depressive symptoms that were related to diabetes had the highest F-values.

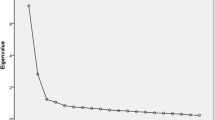

The ability of the PAID questionnaire to screen for clinical depression according to ICD-10 was assessed by using the area under the ROC. The ROC relating to the screening performance of the PAID questionnaire in identifying diabetic patients with clinical depression is displayed in Fig. 1. The AUC for the total score of the PAID questionnaire was 0.83±0.03, which is significantly higher (p<0.001) than the diagonal line, which represents classification by chance (AUC 0.50). A cut-off score for the PAID questionnaire of ≥38 was closest to the intersection of the ROC and the dotted diagonal line. This crossing point provided an optimal balance between sensitivity (81%) and specificity (74%).

A second ROC analysis was performed to determine the ability of the PAID questionnaire to differentiate between diabetic patients with a normal depression score and patients with an elevated depression score according to one of the two depression questionnaires. The latter group comprised not only those patients with clinical depression but also those with subclinical depression. The area under the ROC was 0.84±0.22 (Fig. 2). Thus, the ability of the PAID questionnaire to identify patients with elevated depressive symptoms is equivalent to its ability to identify diabetic patients with clinical depression. For the identification of subclinical and clinical depression, a lower cut-off score of ≥33 seemed to be appropriate (sensitivity=79% and specificity=76%).

We compared the screening performance of the PAID questionnaire regarding the diagnosis of clinical depression with the diagnostic performance of routine assessment in clinical care (SCA) and the two depression questionnaires, BDI and CES-D (Table 3). The SCA had the lowest sensitivity for the detection of clinical depression. Additional screening for depression enhanced the sensitivity of the screening procedure remarkably. Measuring diabetes-specific distress with the PAID questionnaire increased sensitivity to more than 80%, which was equivalent to the sensitivity of the CES-D. The BDI yielded the highest sensitivity for the detection of clinical depression. A sensitivity of >90% resulted from the combination of the two depression questionnaires, but at the expense of a lower specificity (78%). In summary, the screening performance for detection of clinical depression with the PAID questionnaire was markedly higher than that of SCA, slightly lower than with the BDI, but equivalent to using the CES-D. Positive predictive values of the questionnaires (BDI, CES-D, and PAID) were rather low, whereas negative predictive values were satisfactorily high.

The screening performance of the PAID questionnaire, compared with the SCA and clinical depression diagnoses (CIDI and SCA), in detecting subclinical depression is shown in Table 4. The SCA and clinical depression diagnosis had rather low sensitivity in detecting subclinical depression, whereas the PAID questionnaire had an acceptable ability to detect subclinical depression. Negative predictive values for the PAID questionnaire were acceptable, whereas those of SCA and clinical depression diagnosis were markedly lower, indicating a high frequency of false negative results.

Since diabetes-related emotional distress per se has a negative impact on self-management of the disease, we studied the ability of depression measures to detect diabetes-specific emotional distress (Table 5). Clearly, the SCA and clinical depression diagnosis (SCA and CIDI) had very low sensitivity in detecting diabetes-related emotional problems. Using the two depression questionnaires with the cut-off scores suggested for the detection of depression enhanced the sensitivity of the screening for diabetes-specific emotional problems to 49% (CES-D) and 60% (BDI); however, this procedure left 51 and 40%, respectively, of the patients with diabetes-related distress undetected. Using the combination of two depression questionnaires enhanced sensitivity to 67%. As can be derived from the negative predictive value of the different depression measures, 14.8–27.5% of the diabetic patients with a negative depression screening result displayed evidence of diabetes-related emotional distress.

However, analysis of the ROC characteristics of the two depression questionnaires demonstrated a satisfactory screening performance (BDI, AUC=0.85±0.02; CES-D, AUC=0.80±0.02), but suggested markedly lower cut-off scores than those used for depression diagnosis. For the BDI a cut-off of >7 was suggested, for the CES-D a cut-off of >14.

Discussion

Screening for depression is recommended in several guidelines for psychosocial care. This study focused on the question of the most appropriate method to detect depressive disorders in diabetic patients through the use of depression-specific measures as well as the assessment of diabetes-related distress.

In our sample, 14.1% of patients received a diagnosis of clinical depression. In addition, 18.9% of the diabetic patients showed evidence of subclinical depression; thus, 33.0% of the studied sample suffered from depressive symptoms. Although this rate is slightly higher than would be expected from the findings of meta-analyses, the prevalence of depression in our sample was close to that which would be expected from other studies of depression and diabetes [11, 32]. The slightly higher rate in our sample could be explained by the fact that the specialised diabetes centre may have attracted patients who had more problems, including more depression, than the average patient with diabetes.

The study provides an overview of different depression measures for depression screening in diabetic patients. With regard to duration, the rather intensive SCA, lasting approximately 45 min, is a relatively favourable example of current clinical practice, in which the average visit lasts between 2 and 15 min [33, 34]. In spite of these rather generous time resources, the sensitivity of the SCA for the detection of clinical depression was 56%. Although this result was far better than the currently estimated detection rate [35], it means that 44% of diabetes patients who were currently clinically depressed would have remained undiagnosed. Since even under rather favourable circumstances the sensitivity of the SCA for clinical depression is moderate, additional screening for depression in diabetic patients seems to be reasonable. The use of general depression questionnaires can increase the sensitivity to 90%. Since the lower 95% confidence limit of sensitivity of the two depression questionnaires is clearly distinct from the upper 95% confidence limit of sensitivity of the SCA, this increase in screening performance could be regarded as substantial.

Although the benefits of depression questionnaires for depression screening in the general population as well as in diabetic patients have been demonstrated previously [36, 37], general depression questionnaires have not been widely used, given the low detection rate of 25% in diabetic patients [35]. Researchers may speculate about the reasons for this state of affairs. One reason could be that the primary expectation of diabetic patients who seek diabetic care is to be treated for their somatic disease. Questions about symptoms, such as loss of interest, suicide ideation and feelings of guilt, have no apparent reference to diabetes [35]. Healthcare professionals as well as diabetic patients may not be inclined initially to ask or answer questions about general emotional distress or to complete depression questionnaires. The measurement of diabetes-specific emotional distress using the PAID questionnaire may provide an alternative that better fits the expectations of diabetic patients and their health-care providers.

Although the PAID questionnaire was designed originally to measure emotional problems related to diabetes [22–25], our study has demonstrated that it can be used to screen for clinical as well as subclinical depression in patients with diabetes. The AUC of the ROC, indicating the screening performance of the PAID questionnaire in detecting clinical depression, was satisfactorily high. The screening performance of the PAID questionnaire for depression in diabetes seems to be equivalent to or slightly better than that of the CES-D, whereas the BDI seems to have a slightly higher screening performance. A comparison of the screening performance of the PAID questionnaire in diabetic patients with that of the CES-D and BDI in the general population yielded a similar result [38–43]. In summary, the screening performance of the PAID questionnaire, as a measure of diabetes-specific emotional distress, is quite comparable to that of the two specific and commonly used depression questionnaires mentioned above and substantially higher than that of the SCA.

The negative consequences of depression in diabetes are not restricted to patients who suffer from clinical depression; such consequences are also manifested by diabetic patients who have elevated depressive symptoms [3, 5, 10]. Furthermore, some prospective studies have demonstrated that non-diabetic people with elevated depressive symptoms have a six-fold higher risk of developing clinical depression in the future [44–47]. Identifying diabetic patients with subclinical depression therefore seems essential so that steps can be taken to avoid deterioration of the depressive state [48]. By using the lower cut-off score of ≥33, as suggested by the ROC analysis, the PAID questionnaire seems to be as good in detecting subclinical depression as in detecting clinical depression, whereas the SCA or diagnostic procedures that concentrate on clinical depression have rather poor sensitivity.

Diabetes-specific distress, as measured by the PAID questionnaire, was most frequently related to worries concerning future complications and hypoglycaemic reactions. Although all items of the PAID questionnaire were able to discriminate among the three groups with different depression states, typical depressive symptoms, such as feeling depressed or overwhelmed, or burned out by diabetes or its management, yielded the highest F-values in univariate ANOVAs, indicating that several items of the PAID questionnaire are more specifically related to general states of emotional distress, such as depression.

As we demonstrated, depression is not the only common emotional problem in diabetic patients; many diabetic patients are also affected by diabetes-related distress. Use of the PAID questionnaire for the routine assessment of emotional problems in diabetes and in the communication of the outcome to the patients resulted in higher quality of life and reduced mental health problems in those patients [49].

Although there is considerable overlap of patient subgroups with depression and diabetes-related distress, the two subgroups are not identical. Since diabetes-specific distress seems to have an independent negative impact on glycaemic control and self-management [7], the assessment of these problems seems reasonable. In addition to providing an initial, non-threatening screen for depression, knowledge about diabetes-related distress could be taken into account in the formulation of diabetes treatment plans or specific interventions (e.g. providing training in blood glucose awareness for diabetic patients who are worried about hypoglycaemic reactions).

This study also investigated the screening ability of the depression measures to identify patients with a great amount of diabetes-related distress. The SCA and the diagnosis of clinical depression have rather poor sensitivity in detecting these diabetes-specific emotional problems, whereas the depression questionnaires have intermediate sensitivity. Improving the screening abilities of these depression questionnaires would require the selection of lower cut-off scores. But using lower cut-off scores implies that a great proportion of diabetic patients are screened positive, given the right-shifted distribution of depression scores in diabetic samples. Patients who are screened positive would need further diagnostic steps to find out the specific emotional problems related to diabetes. In summary, these results indicate that reliance solely on depression measures carries a high risk of not identifying patients who have a great amount of diabetes-related distress.

Finally, the methodological limitations of this study should be kept in mind when interpreting its results. This study had a two-step approach. The first step was screening for depression and the assessment of diabetes-specific emotional distress. In patients who screened positive for depression, a standardised psychodiagnostic interview was performed as the gold standard test. Such a two-stage procedure, in which only patients who screen positive receive the gold standard test, is prone to so-called verification bias [28], which cannot exclude the possibility that true positive cases have not been identified. To minimise this bias, we enhanced the sensitivity of the depression screening by using two depression questionnaires and inviting patients who screened positive in one of them to participate in the CIDI. Given the high sensitivity of both depression questionnaires [37], the independent probability of a false negative screening result is low (approximately <2%). Furthermore, diagnoses from the entry examination on hospital admission were checked to identify patients who were screened false negative. We were able to identify four additional patients with concurrent antidepressive treatment but remitted depressive symptoms. However, in spite of these measures, we cannot definitively exclude the possibility that there were false negative results in the depression diagnoses.

A further limitation of the study could be that the sample consisted of diabetic patients treated in an inpatient setting. Thus, it cannot be ruled out that these patients suffered from more diabetes-related distress than diabetic patients in an outpatient setting. Therefore, replication in an outpatient setting would be desirable in order to verify the suggested cut-off scores for the PAID questionnaire in the patients in our sample.

In the face of high prevalence rates for depression [11], screening for depression is often recommended [19, 20]. This study indicates that the SCA, performed even under favourable clinical circumstances, has limited sensitivity for the detection of clinical as well as subclinical depression. Screening performance for depression could be enhanced substantially by the use of depression questionnaires or the measurement of diabetes-related emotional distress by the PAID questionnaire.

In modern diabetes care the assessment of diabetes-related emotional problems is of great clinical utility for the improvement of diabetes outcomes as well as for quality of life [22]. Using depression measures to screen for diabetes-related emotional distress resulted in poor to modest screening performance.

If we assume that screening by means of multiple questionnaires is regarded as unfavourable because of time and resource restrictions in clinical practice, the PAID questionnaire could be used for the assessment of emotional distress related to diabetes as well as for screening for depression in diabetes.

Abbreviations

- BDI:

-

Beck Depression Inventory

- CES-D:

-

Center of Epidemiological Studies – Depression Scale

- CIDI:

-

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision

- PAID:

-

Problem Areas in Diabetes

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristic curve

- SCA:

-

standard clinical assessment

References

Lustman PJ, de Groot M, Anderson RJ, Carney RM, Freedland KE, Clouse RE (2000) Depression and poor glycemic control. Diabetes Care 23:934–942

de Groot M, Anderson RJ, Freedland KE, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ (2001) Association of depression and diabetes complications: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med 63:619–630

Egede LE (2004) Diabetes, major depression, and functional disability among US adults. Diabetes Care 27:421–428

Black SA, Markides KS, Ray LA (2003) Depression predicts increased incidence of adverse health outcomes in older Mexican Americans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 26:2822–2828

Pouwer F, Beekman ATF, Nijpels G et al. (2003) Rates and risks for co-morbid depression in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: results of a community based study. Diabetologia 46:892–898

Ciechanowski PS, Wayne MPH, Katon J, Russo JE (2000) Depression and diabetes. Impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function and costs. Arch Intern Med 160:3278–3285

Polonsky WH, Jacobson A, Anderson B et al (1995) Assessment of diabetes-related-distress. Diabetes Care 18:754–760

Rubin RR (2000) Diabetes and quality of life. Preface. Diabetes Spectrum 13:21–23

Rubin RR, Peyrot M (1999) Quality of life and diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 15:205–218

Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K (2002) Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care 25:464–470

Anderson RJ, Freedland KF, Clouse RE, Lustman PJ (2001) The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 24:1069–1078

Peyrot M, Rubin RR (1997) Levels and risks of depression and anxiety symptomatology among diabetic adults. Diabetes Care 20:585–590

Talbot F, Nouwen AA (2000) Review of the relationship between depression and diabetes in adults: is there a link? Diabetes Care 23:1556–1562

Fischer L, Skaff MM, Chelsa CA, Kanter RA, Mullan JT (2001) Contributors to depression in Latino and European-American patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 24:1751–1757

Hermanns N, Kulzer B, Krichbaum M, Kubiak T, Haak T (2005) Affective and anxiety disorders in a German sample of diabetic patients: prevalence, comorbidity and risk factors. Diabet Med 22:293–300

Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Clouse RE et al (1997) Effects of nortripyline on depression and glucose regulation in diabetes: results of a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Psychosom Med 59:241–250

Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Freedland KE, Clouse RE (2000) Fluoxetine for depression in Diabetes. Diabetes Care 23:618–623

Lustman PJ, Griffith LS, Freedland KE, Kissel SS, Clouse RE (1998) Cognitive behavior therapy for depression in type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 129:613–621

American Diabetes Association (2005) Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care 28 (Suppl 1):S4–S36

Petrak F, Herpertz S, Albus C, Hirsch A, Kulzer B, Kruse J (2005) Psychosocial factors and diabetes mellitus: evidence based treatment guidelines. Curr Diab Rev 1 (in press)

Snoek FJ, Pouwer F, Welch GW, Polonsky WH (2000) Diabetes related emotional stress in Dutch and US diabetic patients: cross-cultural validity of the problem areas in diabetes scale. Diabetes Care 23:1305–1309

Welch GW, Jacobson AM, Polonsky WH (1997) The Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale. An evaluation of its clinical utility. Diabetes Care 20:760–766

Weinger K, Jacobson AM (2001) Psychosocial and quality of life correlates of glycemic control during intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. Patient Educ Couns 42:123–131

Welch G, Weinger K, Anderson B, Polonsky WH (2003) Responsiveness of the Problem Areas In Diabetes (PAID) questionnaire. Diabet Med 20:69–72

Hautzinger M, Bailer M, Worral H, Keller F (1994) Beck-Depressions-Inventar (BDI). Hogrefe, Göttingen

Hautzinger M, Bailer J (1993) Allgemeine Depressions-Skala. Hogrefe, Göttingen

Wittchen HU (1994) Reliability and validity studies of the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): a critical review. J Psychiatr Res 28:57–84

Reid MC, Lachs MS, Feinstein AR (1995) Use of methodological standards in diagnostic test research. Getting better but still not good. JAMA 274:645–651

Kulzer B, Hermanns N, Ebert M, Kempe J, Kubiak T, Haak T (2002) Problembereiche bei Diabetes (PAID)—Ein neues Messinstrument zur Erfassung der Emotionalen Anpassung an Diabetes. Diabetes Stoffwechsel 11 (Suppl 1):144

Pouwer F, Skinner TC, Pibernik-Okanovic M et al (2005) Serious diabetes-specific emotional problems and depression in a Croatian-Dutch-English Survey from the European Depression in Diabetes [EDID] Research Consortium. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 70:166–173

Bland M (2000) An introduction to medical statistics. 3rd edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Kruse J, Schmitz N, Thefeld W (2003) On the association between diabetes and mental disorders in a community sample. Diabetes Care 26:1841–1846

Tahepold H, Maaroos HI, Kalda R, Brink-Muinen A (2003) Structure and duration of consultations in Estonian family practice. Scand J Prim Health Care 21:167–170

Bensing JM, Roter DL, Hulsman RL (2003) Communication patterns of primary care physicians in the United States and the Netherlands. J Gen Intern Med 18:335–342

Rubin RR, Ciechanowski P, Egede LE, Lin EH, Lustman PJ (2004) Recognizing and treating depression in patients with diabetes. Curr Diab Rep 4:119–125

Lustman PJ, Clouse RE, Griffith LS, Carney RM, Freedland KE (1997) Screening for depression in diabetes using the Beck Depression Inventory. Psychosom Med 59:24–31

Williams JW Jr, Pignone M, Ramirez G, Perez SC (2002) Identifying depression in primary care: a literature synthesis of case-finding instruments. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 24:225–237

Garrison CZ, Addy CL, Jackson KL, McKeown RE, Waller JL (1991) The CES-D as a screen for depression and other psychiatric disorders in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30:636–641

Roberts RE, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR (1991) Screening for adolescent depression: a comparison of depression scales. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 30:58–66

Furukawa T, Hirai T, Kitamura T, Takahashi K (1997) Application of the Center of Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale among first-visit psychiatric patients: a new approach to improve its performance. J Affect Disord 46:1–13

Andriushchenko AV, Drobizhev MI, Dobrovol’skii AV (2003) [A comparative validation of the scale CES-D, BDI, and HADS(d) in diagnosis of depressive disorders in general practice]. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova 103:11–18

Leentjens AF, Verhey FR, Luijckx GJ, Troost J (2000) The validity of the Beck Depression Inventory as a screening and diagnostic instrument for depression in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 15:1221–1224

Lasa L, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Vazquez-Barquero JL, Diez-Manrique FJ, Dowrick CF (2000) The use of the Beck Depression Inventory to screen for depression in the general population: a preliminary analysis. J Affect Disord 57:261–265

Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS (2002) The prevalence, clinical relevance, and public health significance of subthreshold depression. Psychiatr Clin North Am 25:685–698

Judd LL, Rapaport MH, Paulus MP, Brown JL (1994) Subsyndromal symptomatic depression (SSD): a new mood disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 55:18S–28S

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Paulus MP (1997) The role and clinical significance of subsyndromal depressive symptoms (SSD) in unipolar major depressive disorder. J Affect Dis 45:5–17

Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD et al (1998) Major depressive disorder: a prospective study of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. J Affect Dis 50:97–108

Peyrot M (2003) Depression: a quiet killer by any name. Diabetes Care 26:2952–2953

Pouwer F, Snoek FJ, Van Der Ploeg HM, Ader HJ, Heine RJ (2001) Monitoring of psychological well-being in outpatients with diabetes: effects on mood, HbA(1c), and the patient’s evaluation of the quality of diabetes care: a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 24:1929–1935

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hermanns, N., Kulzer, B., Krichbaum, M. et al. How to screen for depression and emotional problems in patients with diabetes: comparison of screening characteristics of depression questionnaires, measurement of diabetes-specific emotional problems and standard clinical assessment. Diabetologia 49, 469–477 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-0094-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-0094-2