Abstract

Introduction

Little is known about the characteristics of dying in different care settings, such as the hospital, the nursing home, or the home-care setting.

Materials and methods

We measured the burden of symptoms, medical and nursing interventions, and aspects of communication during the last 3 days of life within each of these settings. We included 239 of 321 patients (74%) who died in one of these settings in the southwest of The Netherlands, between November 2003 and February 2005. After the patient’s death, a nurse filled in a questionnaire.

Results

Pain and shortness of breath were more severe in hospital patients as compared to nursing home and home-care patients, whereas incontinence was less severe in hospital patients. Several medical interventions, such as a syringe driver, vena punctures or lab tests, radiology or ECG, antibiotics, and drainage of body fluids were more often applied during the last 3 days of life to hospital patients than to nursing home and home-care patients. This also holds for the measurement of body temperature and blood pressure. In the hospital setting, the patient and the family were more often informed about the imminence of death of the patient than elsewhere. The general practitioner and other professional caregivers were less often informed about the imminence of death of hospital patients than of other patients.

Discussion

We conclude that pain and shortness of breath were more severe among hospital patients, whereas incontinence was more severe among nursing home and home-care patients. Hospital patients relatively often receive medical interventions and standard controls during the last 3 days of life. In hospital, communication about impending death seems to take place more often shortly before death.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Most people prefer to die at home [1]. In many Western countries, however, a major proportion of the population dies in a hospital [2]. In the USA, England and Wales, Germany, Switzerland, and France, more than half of all deaths occur in a hospital [2]. In The Netherlands, a relatively small percentage of about 35% of all deaths occur in a hospital, about 23% of all deaths occur in nursing homes, and people relatively often (42%) die at home [3]. This holds even stronger for patients who die of cancer: Sixty-five percent of cancer deaths occur at home, whereas only a quarter occurs in a hospital [4]. The place of death has been shown to be related to several factors: people are more likely to die at home when competent informal caregivers are available and when professional health care services can be provided at home [5–7]. An increase in the complexity and intensity of patients’ care needs is associated with admittance to a nursing home or hospital. The chance of dying in a hospital further increases with the availability of nearby hospital beds [8].

WHO Europe propagates optimisation of palliative care within both the institutional setting and at home [9]. Nevertheless, substantial proportions of patients dying in hospitals or nursing homes were shown to have received poor symptom control and insufficient emotional support [10–15]. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments among bereaved relatives in the USA also concluded that many patients dying in hospitals have unmet needs concerning symptom relief and psychosocial care [11, 16]. It is often suggested that enabling people to die at their place of preference, that is, at home, may contribute to their quality of dying. However, relatively little is known about the care for patients dying at home and about differences in care between settings. Therefore, we aimed to investigate care for dying patients in the hospital setting, the nursing home setting, and the home-care setting. In The Netherlands, patients at home receive care from their general practitioner and, if needed, from home-care nurses who may visit patients once or several times a day. Nursing home residents typically have chronic conditions for which access to constant care, 24 h a day, is needed. The nursing home physician and nurses provide nursing home care. In hospitals, patients receive care from medical specialists and hospital nurses. Patients are typically admitted to a hospital for specialized, mostly short-term care that cannot be given elsewhere.

Our study encompasses the characteristics of care and quality of life during the last 3 days of life within these three care settings in The Netherlands. We looked at the symptom burden, the application of medical and nursing interventions, and at some aspects of the communication between patients, family, and professional caregivers.

Materials and methods

Patients

We did an observational study. A number of health care institutions in the southwest region of The Netherlands that were known to be interested in end-of-life care participated. They represented the three types of end-of-life care settings: the hospital setting, the nursing home setting, and the home-care setting. The hospital setting included a medical oncology department in a general hospital, and two medical oncology departments as well as a department for pulmonary diseases and a gynecology department in a university hospital. The typical aim of admitting patients to these departments is to provide specialized care for complex problems and to discharge them back home afterwards. Death is relatively rare at most of these departments (two patients per month or less) except for the department of medial oncology of the general hospital, where, on average, five patients die each month. The nursing home setting included a general department and a palliative care department in one nursing home, a complete nursing home that also has a palliative care department, and a residential care organization providing nursing care to people who live in a residential home. The average number of deaths at each nursing home department is one to two per month. The home-care setting was represented by a home-care organization that provides nursing care at home in a region of eight villages and by the residential care organization that also provides nursing care to people living at home. In both home-care organizations, the average monthly number of dying patients is one.

All patients receiving care from either of the participating departments between November 2003 and February 2005 were informed of the study through an information letter. Patients of 18 years or older who died in this period were eligible for the study. Patients who had expressed objections against the use of their medical or nursing record were not included. Patients who could not be informed of the study, mostly because of their weak health status, were not included. Patients who expressed objections against the use of their medical or nursing record after their death were not included either. The Medical Ethical Research Committee of the Erasmus MC approved the study.

Data collection

General information about the patient, like gender, age, and diagnosis, was obtained from the medical and nursing records, as well as information about whether or not the dying phase had been recognized by the caregivers and about communication with other caregivers. Further, within 1 week after the patient’s death, a nurse who had been closely involved in caring for the patient in the last 3 days of life filled in a questionnaire about the patient’s symptoms and the care that had been provided to the patient and the relatives during the last 3 days of life. The questions about dyspnoea, pain, constipation, nausea or vomiting, and diarrhoea originated from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Core Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30). We considered this questionnaire a valid instrument for measuring the patients’ symptom burden by other than patients themselves because the agreement between patients and observers has been shown to be moderate to good (intra class correlation = 0.42 to 0.79) [17]. Questions about agitation, fear, confusion, incontinence, and troublesome mucus production were added because these symptoms are common in the last phase of life. Before its use in our study, the validity of the questionnaire was evaluated in face-to-face interviews with four nurses.

Analysis

Scores on the EORTC QLQ-C30 items were linearly transformed to a 0–100 scale. A higher score on this 0–100 scale reflects more severe symptoms. We compared the symptom burden, the extent to which medical and nursing interventions were applied, and some aspects of communication between the three types of settings. We distinguished cancer and noncancer patients because of the fact that the hospital setting included mainly oncology departments. The degree to which differences in patient characteristics could explain differences in symptom burden, interventions, and communication between settings was analyzed in multivariate linear regression analysis.

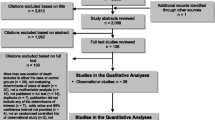

Results

Between November 2003 and February 2005, 321 patients died while receiving care from one of the participating institutions. Thirty-eight patients died at home, 128 patients died in a nursing home, and 155 patients died in the hospital. We included 27 home-care patients (71%), 102 nursing home patients (80%), and 110 hospital patients (71%) in our study. In total, we included 239 patients (74%) in our study (see Fig. 1). Eighty-two deceased patients could not be included. Thirty-two patients (10%) were not able to give informed consent, e.g., because there had been no good moment for the nurse to hand over the information letter to the patient. Twenty patients (6%) had been mentally or physically unable to give informed consent. Seventeen patients (5%) had objected against the use of their medical data in case they died; for 12 patients (4%), information about the reason why no informed consent was obtained is missing. Further, one case was missed because we did not receive a questionnaire back. In total, 153 nurses filled in 239 questionnaires: Most nurses filled in one or two questionnaires, but 11 nurses filled in three or more questionnaires.

Of all included patients, 110 patients (46%) had died in the hospital, 102 patients (43%) in a nursing home, and 27 patients (11%) at home (Table 1). Of all hospital patients, 93% had cancer. This holds for 56% of the home-care patients and 37% of the nursing home patients. Further, patients dying in the hospital setting were relatively young. For the majority of the patients within each setting, caregivers had been aware that the dying phase had started. Further details are presented in Table 1.

Table 2 presents the average EORTC symptom scores as reported by nurses for the last 3 days of life of the patients. Within each setting, fatigue, lack of appetite, shortness of breath, pain, and concentration difficulties had the highest mean scores. In the hospital setting, patients had mean scores higher than 50 for pain and shortness of breath, whereas in the nursing home as well as in the home-care setting, patients had mean scores higher than 40 for incontinence. Of the psychological symptoms, worry had the highest mean score, except in the nursing home setting. Agitation and tenseness had moderate mean scores within each setting.

Table 3 shows the percentages of patients in the different settings who underwent medical or nursing interventions during the last 3 days of life. Medication as required was prescribed for most cancer patients and, although to a lesser extent, also to most noncancer patients within each setting. Medical interventions, like setting up of a syringe driver, vena punctures or lab tests, radiology or ECG, antibiotics, and drainage of body fluids were most often applied to hospital patients. Within each setting, the majority of the patients was showered or washed daily. Standard controls, like body temperature measurement, and blood pressure measurement were mainly applied to hospital patients. Other nursing interventions, like wound care, and a routine turning regime were mainly applied to patients in the nursing home and home-care setting.

Table 4 lists some aspects of communication. In the hospital setting, more patients were explicitly informed about the imminence of death. In the majority of the cases within each setting, the family was informed about the imminence of death of the patient. Compared to the nursing home and the hospital setting, the families of home-care patients were less often informed about the imminent death of the patient. General practitioners and other professional caregivers were less often informed about the imminence of death of hospital patients than of nursing home or home-care patients.

Discussion

In our study, we compared characteristics of dying in the hospital setting, the nursing home setting, and the home-care setting. There were some differences in patient characteristics between the settings in our study. Nursing home and home-care patients were older and more often died from noncancer diseases as compared to hospital patients. These differences are typical for the general populations of patients dying in these settings [4], but they are even more pronounced due to the fact that our study comprised several oncology departments in hospitals.

Pain and shortness of breath were more severe among hospital patients, whereas incontinence was more severe among nursing home and home-care patients. Fatigue, lack of appetite, shortness of breath, pain, concentration difficulties, incontinence, worry, agitation, and tenseness have been found as being typical for the last 3 days of life in our study. These symptoms have been found as being typical for the last weeks of life in other studies too [18, 19]. Six percent of the patients who died during the study period could not be included in the study because they were physically or mentally unable to give informed consent. This may have led to a selection of patients with, on average, fewer symptoms than the total population of deceased patients.

Several medical and nursing interventions were most often applied in the hospital setting. The palliative care approach assumes that treatments that are exclusively aimed at prolonging the patient’s life and interventions aimed at assessing the patient’s health condition, such as blood pressure and body temperature measurements, become minor to efforts that give patients the opportunity to invest their energy in saying goodbye to loved ones and in other issues to complete life. However, caregivers may be reluctant to refrain from routine interventions in dying patients, especially when the dying phase has not been recognized. In the hospital setting, for example, standard controls were continued in a substantial minority of the patients. Caregivers may find it difficult to shift from a curative approach to a palliative approach [20]. Our finding that some hospital patients were informed about the imminence of their death and received antibiotics in the same period suggests that the transition from ‘cure’ to ‘care’ occurs often very shortly before death. The earlier awareness of a patient’s impending death, may, especially in the hospital setting, facilitate a shift from the focus of care from prolonging life to accepting death.

In several studies, both patients and family have been shown to consider clear information about what to expect during the dying phase as very important [21, 22]. We found that, in the hospital setting, patients and family were indeed relatively often informed of the imminent death of the patient in the last 3 days of life. This might be related to several factors. First, in the nursing home and at home, end-of-life care may already have been discussed at an earlier stage. Second, our hospital setting included mostly cancer patients. Most cancer patients keep a high function level until shortly before death [23]. Not only may cancer patients remain able to communicate until shortly before death. Their decline in the terminal stage may also necessitate explicit communication about the imminence of death. Third, hospital care is, in general, aimed at temporary treatment to send patients home as soon as their health condition allows. In the last phase of life, the families of cancer patients have usually not given their farewells to the patient [24]. As a result, dying typically represents an unexpected course of events in hospital that possibly induces relatively clear communication about the imminence of death and its consequences for the decision making about medical and nursing care.

When interpreting the results, we have to be aware of some limitations of this study that are mostly typically associated with end-of-life research. To start with, all data were collected after the death of the patient. Obviously, the exact time of death of the patient could not be foreseen in most cases. Our data, therefore, do not warrant direct conclusions about the quality of care for dying patients in different settings. They are primarily aimed at enabling evaluation of the different practices. Further, the majority of the nurses (81%) filled in the questionnaire within 7 days after the death of the patient. We assume that within such a short timespan, the nurses who had been closely involved with care for the patient during the last 3 days of life were able to recall most care details, but it can not be precluded that the degree of involvement and recall bias is different between the settings.

We conclude that, in the hospital setting, patients have more pain and shortness of breath, whereas, in the nursing home setting and at home, patients have more severe incontinence. Medical and nursing interventions are in general more often continued during the last 3 days of life in the hospital than in the nursing home or home-care setting. Communication about the imminence of death is more explicit during the last 3 days of life in the hospital than in the other settings.

References

Higginson IJ, Sen-Gupta GJ (2000) Place of care in advanced cancer: a qualitative systematic literature review of patient preferences. J Palliat Med 3(3):287–300

WHO Europe (2004) Evidence of underassessment and undertreatment. In: Davies E, Higginson IJ (eds) Better palliative care for older people. World Health Organization, p 21

Statistics Netherlands (2001) Central Death Registry

Francke AL (2003) Palliative care for terminally ill patients in The Netherlands. Dutch government policy. The Hague: Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport

Visser G, Klinkenberg M, Broese van Groenou MI, Willems DL, Knipscheer CP, Deeg DJ (2004) The end of life: informal care for dying older people and its relationship to place of death. Palliat Med 18(5):468–477

Tang ST, McCorkle R (2003) Determinants of congruence between the preferred and actual place of death for terminally ill cancer patients. J Palliat Care 19(4):230–237

Klinkenberg M, Visser G, van Groenou MI, van der Wal G, Deeg DJ, Willems DL (2005) The last 3 months of life: care, transitions and the place of death of older people. Health Soc Care Community 13(5):420–430

Pritchard RS, Fisher ES, Teno JM, Sharp SM, Reding DJ, Knaus WA et al (1998) Influence of patient preferences and local health system characteristics on the place of death. SUPPORT investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for risks and outcomes of treatment. J Am Geriatr Soc 46(10):1242–1250

WHO Europe (2004) Policies for palliative care need to be developed as part of an innovative global public health policy. In: Davies E, Higginson IJ (eds) The solid facts, palliative care. World Health Organization, p 14

Plonk WM Jr, Arnold RM (2005) Terminal care: the last weeks of life. J Palliat Med 8(5):1042–1054

Lynn JTJ, Phillips RS, Wu AW, Desbiens N, Harrold J, Claessens MT, Wenger N, Kreling B, Connors AF Jr (1997) Perceptions by family members of the dying experience of older and seriously ill patients. SUPPORT investigators. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. Ann Intern Med 126:97–106

Toscani F, Di Giulio P, Brunelli C, Miccinesi G, Laquintana D (2005) How people die in hospital general wards: a descriptive study. J Pain Symptom Manage 30(1):33–40

DeSilva DL, Dillon JE, Teno JM (2001) The quality of care in the last month of life among Rhode Island nursing home residents. Med Health R I 84(6):195–198

Hall P, Schroder C, Weaver L (2002) The last 48 hours of life in long-term care: a focused chart audit. J Am Geriatr Soc 50(3):501–506

Reynolds K, Henderson M, Schulman A, Hanson LC (2002) Needs of the dying in nursing homes. J Palliat Med 5(6):895–901

Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R et al (2004) Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA 291(1):88–93

Sneeuw KC, Aaronson NK, Sprangers MA, Detmar SB, Wever LD, Schornagel JH (1998) Comparison of patient and proxy EORTC QLQ-C30 ratings in assessing the quality of life of cancer patients. J Clin Epidemiol 51(7):617–631

Coyle N, Adelhardt J, Foley KM, Portenoy RK (1990) Character of terminal illness in the advanced cancer patient: pain and other symptoms during the last four weeks of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 5(2):83–93

Klinkenberg M, Willems DL, van der Wal G, Deeg DJ (2004) Symptom burden in the last week of life. J Pain Symptom Manage 27(1):5–13

The SUPPORT Principal Investigators (1995) A controlled trial to improve care for seriously ill hospitalized patients. The study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments (SUPPORT). JAMA 274(20):1591–1598

Wenrich MD, Curtis JR, Shannon SE, Carline JD, Ambrozy DM, Ramsey PG (2001) Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med 161(6):868–874

Osse BH, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Schade E, de Vree B, van den Muijsenbergh ME, Grol RP (2002) Problems to discuss with cancer patients in palliative care: a comprehensive approach. Patient Educ Couns 47(3):195–204

Murray SA, Kendall M, Boyd K, Sheikh A (2005) Illness trajectories and palliative care. BMJ 330(7498):1007–1011

Albinsson L, Strang P (2003) Differences in supporting families of dementia patients and cancer patients: a palliative perspective. Palliat Med 17(4):359–367

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Veerbeek, L., van Zuylen, L., Swart, S.J. et al. The last 3 days of life in three different care settings in The Netherlands. Support Care Cancer 15, 1117–1123 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0211-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0211-x