Abstract

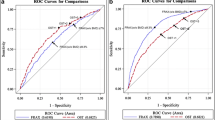

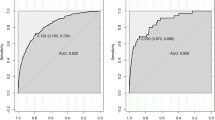

Osteoporosis and its consequent increase in fracture risk is a major health concern for postmenopausal women and older men and has the potential to reach epidemic proportions. The “gold standard” for osteoporosis diagnosis is bone densitometry. However, economic issues or availability of the technology may prevent the possibility of mass screening. The goal of this study was to develop and validate a clinical scoring index designed as a prescreening tool to help clinicians identify which women are at increased risk of osteoporosis [bone mineral density (BMD) T-score −2.5 or less] and should therefore undergo further testing with bone densitometry. Records were analyzed for 1522 postmenopausal females over 50 years of age who had undergone testing with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Osteoporosis risk index scores were compared to bone density T-scores. Hologic QDR 4500 technology was used to measure BMD at the femoral neck and lumbar spine (L1–L4). Participants who had a previous diagnosis of osteoporosis or were taking bone-active medication were excluded. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to identify the specific cutpoint value that would identify women at increased risk of low BMD. A simple algorithm based on age, weight, history of previous low impact fracture, early menopause, and corticosteroid therapy was developed. Validation of this five-item osteoporosis prescreening risk assessment (OPERA) index showed that the tool, at the recommended threshold (or cutoff value) of two, had a sensitivity that ranged from 88.1 [95% confidence interval (CI) for the mean: 86.2–91.9%] at the femoral neck to 90% (95% CI for the mean: 86.1–93.1%) at the lumbar spine area. Corresponding specificity values were 60.6 (95% CI for the mean: 57.9–63.3%) and 64.2% (95% CI for the mean: 61.4–66.9%), respectively. The positive predictive value (PPV) ranged from 29 at the femoral neck to 39.2% at the lumbar spine, while the corresponding negative predictive values (NPVs) reached 96.5 and 96.2%, respectively. Based on this cutoff value, the area under the ROC curve was 0.866 (95% CI for the mean: 0.847–0.882) for the lumbar spine and 0.814 (95% CI for the mean: 0.793–0.833) for the femoral neck. We conclude that the OPERA is a free and effective method for identifying Italian postmenopausal women at increased risk of osteoporosis. Its use could facilitate the appropriate and more cost-effective use of bone densitometry in developing countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Riggs BL, Melton LJ III (1995) The worldwide problem of osteoporosis: insights afforded by epidemiology. Bone 17:S505–S511

O’Neill TW, Felsenberg D, Varlow J et al (1996) The prevalence of vertebral deformity in European men and women: the European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Miner Res 11:1010–1018

Reginster JY, Gillet P, Ben Sedrine W, Brands G, Ethgen O, de Froidmont C et al (1999) Direct costs of hip fractures in patients over 60 years old, in Belgium. Pharmacoeconomics 15:507–514

Autier P, Haentjens P, Bentin J, Baillon JM, Grivegne’ AR, Closon MC et al (2000) Costs induced by hip fractures: a prospective controlled study in Belgium. Osteoporos Int 11:373–380

Wolinsky FD, Fitzgerald JF, Stump TE (1997) The effect of hip fracture on mortality, hospitalization, and functional status: a prospective study. Am J Public Health 87:398–403

Randell AG, Nguyen TV, Bhalerao N, Silverman SL, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA (2000) Deterioration in quality of life following hip fracture: a prospective study. Osteoporos Int 11:460–466

Adachi JD, Ioannidis G, Berger C, Joseph C, Papaioannou A, Pickard L et al (2001) The influence of osteoporotic fractures on health-related quality of life in community-dwelling men and women across Canada. Osteoporos Int 12:903–908

Adachi JD, Ioannidis G, Olszynki P, Brown JP, Hanley DA, Sebaldt RJ et al (2002) The impact of incident vertebral and non-vertebral fractures on health related quality of life in postmenopausal women. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 3:11

Martin AR, Sornay-Rendu E, Chandler JM, Duboeuf F, Girman CJ, Delmas PD (2002) The impact of osteoporosis on quality of life: the OFELY cohort. Bone 31:32–36

Kado DM, Browner WS, Palermo L et al (1999) Vertebral fractures and mortality in older women. A prospective study. Arch Intern Med 159:1215–1220

White BL, Fisher WD, Laurin CA (1987) Rate of mortality for elderly patients after fracture of the hip in the 1980s. J Bone Joint Surg Am 69:1335–1340

Gold DT (2001) The nonskeletal consequences of osteoporotic fractures. Psychologic and social outcomes. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 27:255–262

Randell AG, Sambrook PN, Nguyen TV, Lapsley H, Jones G, Kelly PJ, Eisman JA (1995) Direct clinical and welfare costs of osteoporotic fractures in elderly men and women. Osteoporos Int 5:427–432

Oleksik A, Lips P, Dawson A et al (2000) Health-related quality of life in postmenopausal women with low BMD with or without prevalent vertebral fractures. J Bone Miner Res 15:1384–1392

Johannesson M, Jönsson B (1993) Economic evaluation of osteoporosis prevention. Health Policy 24:103–124

Max W, Sinnot P, Kao C, Sung H-Y, Rice DP (2002) The burden of osteoporosis in California, 1998. Osteoporos Int 13:493–500

Marshall D, Johnell O, Wedel H (1996) Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 312:1254–1259

Marshall DA, Sheldon TA, Jonsson E (1997) Recommendations for the application of bone density measurement. What can you believe? Int J Technol Assess Health Care 13:411–419

World Health Organization (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 843:1–129

Genant HK, Engelke K, Fuerst T et al (1996) Noninvasive assessment of bone mineral and structure: state of the art. J Bone Miner Res 11:707–730

Brown JP, Josse RG for the Scientific Advisory Council of the Osteoporosis Society of Canada (2002) 2002 clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis in Canada. CMAJ 167 [Suppl 10]:S1–S34

Ben Sedrine W, Broers P, Devogelaer JP et al (2002) Interest of a prescreening questionnaire to reduce the cost of bone densitometry. Osteoporos Int 13:434–442

Black DM (1996) Screening and treatment in the elderly to reduce osteoporotic fracture risk. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 103:2–8

Brenneman SK, Lacroix AZ, Buist DS, Chen YT, Abbott TA (2003) Evaluation of decision rules to identify postmenopausal women for intervention related to osteoporosis. Dis Manag 6:159–168

Kanis JA, Delmas P, Burckhardt P, Cooper C, Torgerson D (1997) Guidelines for diagnosis and management of osteoporosis. The European Foundation for Osteoporosis and Bone Disease. Osteoporos Int 7:390–406

National Osteoporosis Foundation (1998) Physician’s guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Excerpta Medica, Belle Mead

NIH Consensus Development Panel on Osteoporosis Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy (2001) Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. JAMA 285:785–795

Società Italiana dell’Osteoporosi del Metabolismo Minerale e delle Malattie dello Scheletro (SIOMMMS) (2002) Osteoporosi: linee guida diagnostiche. http://www.siommms.it/guida.htm

Ben Sedrine W, Devogelaer JP, Kaufman JM, Goemaere S, Depresseux G, Zegels B et al (2001) Evaluation of the simple calculated osteoporosis risk estimation in a sample of Caucasian women from Belgium. Bone 29:374–380

Caderette SM, Jaglal SB, Murray TM (1999) Validation of the simple calculated osteoporosis risk estimation (SCORE) for patient selection for bone densitometry. Osteoporos Int 10:85–90

Cadarette SM, Jaglal SB, Kreiger N, McIsaac WJ, Darlington GA, Tu JV (2000) Development and validation of the osteoporosis risk assessment instrument to facilitate selection of women for bone densitometry. CMAJ 162:1289–1294

Koh LK, Sedrine WB, Torralba TP et al (2001) Osteoporosis self-assessment tool for Asians (OSTA) research group. A simple tool to identify Asian women at increased risk of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 12:699–705

Weinstein L, Ullery B (2000) Identification of at-risk women for osteoporosis screening. Am J Obstet Gynecol 183:547–549

Wynd CA, Schaefer MA (2002) The osteoporosis risk assessment tool: establishing content validity through a panel of experts. Appl Nursing Res 16:184–188

Adami S, Giannini S, Giorgino R, Isaia GC, Maggi S, Sinigaglia L, Filipponi P, Crepaldi G, Di Munno O (2003) The effect of age, weight, and lifestyle factors on calcaneal quantitative ultrasound: the ESOPO study. Osteoporos Int 14:198–207

Nguyen TV, Kelly PJ, Sambrook PN, Gilbert C, Pocock NA, Eisman JA (1994) Lifestyle factors and bone density in the elderly: implications for osteoporosis prevention. J Bone Miner Res 9:1339–1345

Hannan MT, Felson DT, Dawson-Hughes B et al (2000) Risk factors for longitudinal bone loss in elderly men and women: the Framingham osteoporosis study. J Bone Miner Res 15:710–720

Lunt M, Masaryk P, Scheidt-Nave C et al (2001) The effects of lifestyle, dietary dairy intake and diabetes on bone density and vertebral deformity prevalence: the EVOS study. Osteoporos Int 12:688–698

Kanders B, Dempster DW, Lindsay R (1988) Interaction of calcium nutrition and physical activity on bone mass in young women. J Bone Miner Res 3:145–149

Kelly PJ, Pocock NA, Sambrook PN, Eisman JA (1990) Dietary calcium, sex hormones and bone mineral density in normal men. BMJ 300:1361–1364

Bauer DC, Browner WS, Cauley JA et al (1993) Factors associated with appendicular bone mass in older women. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Ann Intern Med 118:657–665

Kiel DP, Zhang Y, Hannan MT, Anderson JJ, Felson DT (1996) The effect of smoking at different life stages on bone mineral density in elderly men and women. Osteoporos Int 6:240–248

Burger H, de Laet C, van Daele P et al (1998) Risk factors of increased bone loss in an elderly population: the Rotterdam Study. Am J Epidemiol 147:871–879

Hollenbach KA, Barrett-Connor E, Edelstein SL, Holbrook T (1993) Cigarette smoking and bone mineral density in older men and women. Am J Public Health 83:1265–1270

Hopper JL, Seeman E (1994) The bone density of female twins discordant for tobacco use. N Engl J Med 330:387–392

Law M, Hackshaw A (1997) A meta-analysis of cigarette smoking, bone mineral density and risk of hip fracture: recognition of a major effect. BMJ 15:841–846

Ward KD, Klesges RC (2001) A meta-analysis of the effects of cigarette smoking on bone mineral density. Calcif Tissue Int 68:259–270

Lau E, Donnan S, Barker D, Cooper C (1988) Physical activity and calcium intake in fracture of the proximal femur in Britain. BMJ 297:1141–1143

Holbrook TL, Barrett-Connor EA (1993) Prospective study of alcohol consumption and bone mineral density. BMJ 306:1506–1509

Hansen M, Overgaard K, Riis BJ, Christiansen C (1991) Role of peak bone mass and bone loss in postmenopausal osteoporosis: 12-year study. BMJ 303:961–964

Albrand G, Munoz F, Sornay-Rendu E, DuBoeuf F, Delmas PD (2003) Independent predictors of all osteoporosis-related fractures in healthy postmenopausal women: the OFELY study. Bone 32:78–85

Haugeberg G, Ørstavik RE, Uhlig T, Falch JA, Halse JI, Kvien TK (2002) Clinical decision rules in rheumatoid arthritis: do they identify patients at high risk for osteoporosis? Testing clinical criteria in a population based cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis recruited from the Oslo Rheumatoid Arthritis Register. Ann Rheum Dis 61:1085–1089

Adinoff AD, Hollister JR (1983) Steroid-induced fractures and bone loss in patients with asthma. N Engl J Med 309:265–268

Michel BA, Bloch DA, Wolfe F, Fries JF (1993) Fractures in rheumatoid arthritis: an evaluation of associated risk factors. J Rheumatol 20:1666–1669

Davis JW, Grove JS, Wasnich RD, Ross PD (1999) Spatial relationships between prevalent and incident spine fractures. Bone 24:261–264

Cumming SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, Stone K, Fox KM, Ensrud KE et al (1995) Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of osteoporotic fractures research group. N Engl J Med 332:767–773

Cadarette SM, Jaglal SB, Murray TM, McIsaac WJ, Joseph L, Brown JP (2001) Evaluation of decision rules for referring women for bone densitometry by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. JAMA 286:57–63

van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Abenhaim L, Zhang B, Cooper C (2000) Use of oral corticosteroids and risk of fractures. J Bone Miner Res 15:993–1000

Adachi JD, Olszynski WP, Hanley DA, Hodsman AB, Kendler DL, Siminoski KG (2000) Management of corticosteroid-induced osteoporosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 29:228–251

Dargent-Molina P, Poitiers F, Bréart G for the EPIDOS group (2000) In elderly women weight is the best predictor of a very low bone mineral density: evidence from the EPIDOS study. Osteoporos Int 11:881–888

Sinigaglia L, Nervetti A, Mela Q, Bianchi G, Del Puente A, Di Munno O for the Italian Study Group on Bone Mass in Rheumatoid Arthritis (2000) A multicenter cross sectional study on bone mineral density in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 27:2582–2589

Reginster J-Y, Kung A, Koh L et al (2002) A simple chart for evaluating risk of osteoporosis in Asian women based on the osteoporosis self-assessment tool for Asians (OSTA). Osteoporos Int 13 [Suppl 3]:S30

Lynn MR (1986) Determination and quantification of content validity. Nursing Res 35:382–385

Weinstein L, Ullery B, Bourguignon C (1999) A simple system to determine who needs osteoporosis screening. Obstet Gynecol 93:757–760

Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Jonsson B, De Laet C, Dawson A (2000) Risk of hip fracture according to the World Health Organization criteria for osteopenia and osteoporosis. Bone 27:585–590

Deyo RA, Centor RM (1986) Assessing the responsiveness of functional scales to clinical change: an analogy to diagnostic test performance. J Chron Dis 39:897–906

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ (1982) The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143:29–36

Hanley JA, McNeil BJ (1983) A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology 148:839–843

Pedrazzoni M, Girasole G, Bertoldo F, Bianchi G, Cepollaro C, Del Puente A et al (2003) Definition of a population-specific DXA reference standard in Italian women: the Densitometric Italian Normative Study (DINS). Osteoporos Int 14:978–982

Tellier V, De Maeseneer J, De Prins L, Ben Sedrine W, Gosset C, Reginster JY (2001) Intensive and prolonged health promotion strategy may increase self-reported osteoporosis prevalence among postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int 12:131–135

Johnel O (1996) Advances in osteoporosis: better identification of risk factors can reduce morbidity and mortality. J Intern Med 239:299–304

Sedrine WB, Reginster JY (2002) Risk indices and osteoporosis screening: scope and limits (editorial). Mayo Clin Proc 77:622–623

Scientific Advisory Board, Osteoporosis Society of Canada (1996) Clinical practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of osteoporosis. CMAJ 155:1113–1133

Ben Sedrine WB, Chevallier T, Zegels B, Kvasz A, Micheletti MC, Gelas B, Reginster JY (2002) Development and assessment of the osteoporosis index of risk (OSIRIS) to facilitate selection of women for bone densitometry. Gynecol Endocrinol 16:245–250

Ungar WJ, Josse R, Lee S, Ryan N, Adachi R, Hanley D, Brown J, Breton MC (2000) The Canadian SCORE questionnaire: optimizing the use of technology for low bone density assessment. Simple calculated osteoporosis risk estimate. J Clin Densitom 3:269–280

Lydick E, Cook K, Turpin J, Melton M, Stine R, Byrnes C (1998) Development and validation of a simple questionnaire to facilitate identification of women likely to have low bone density. Am J Manag Care 4:37–48

Adler RA, Tran MT, Petkov VI (2003) Performance of the osteoporosis self-assessment screening tool for osteoporosis in American men. Mayo Clin Proc 78:723–727

Kung AWC, Ho AYY, Sedrine WB, Reginster JY, Ross PD (2003) Comparison of a simple clinical risk index and quantitative bone ultrasound for identifying women at increased risk of osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 14:716–721

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nursing and technical staff of the Osteoporosis Centers, and Dr. Stefania Muti for the data entry.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Members of the GOMA (Gruppo Osteoporosi Medio-Adriatico), who actively took part in this study

C. Morbidelli (Centro Osteoporosi, INRCA, Ancona), M. Sfrappini (Divisione di Geriatria, Ospedale di S. Benedetto del Tronto), M. Pozone (Divisione di Geriatria, Ospedale L’Aquila), R. Ciaschini (Divisione di Geriatria, Ospedale di Fano), A. Tarone (Divisione di Medicina, Ospedale di Rimini), C. Francucci (Clinica di Endocrinologia, Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Salaffi, F., Silveri, F., Stancati, A. et al. Development and validation of the osteoporosis prescreening risk assessment (OPERA) tool to facilitate identification of women likely to have low bone density. Clin Rheumatol 24, 203–211 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-004-1014-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10067-004-1014-4