Abstract

BACKGROUND

Physician communication style affects patients’ perceptions and behaviors. Two aspects of physician communication style, caring and dominance, are often related in that a high caring physician is usually not dominant and vice versa.

OBJECTIVE

This research was aimed at testing the sole or joint impact of physician caring and physician dominance on participant perceptions and behavior during the medical visit.

PARTICIPANTS AND DESIGN

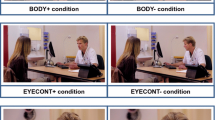

In an experimental design, analog patients (APs) (167 university students) interacted with a computer-generated virtual physician on a computer screen. Participants were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 experimental conditions (physician communication style: high dominance and low caring, high dominance and high caring, low dominance and low caring, or low dominance and high caring). The APs’ verbal and nonverbal behavior during the visit as well as their perception of the virtual physician were assessed.

RESULTS

Analog patients were able to distinguish dominance and caring dimensions of the virtual physician’s communication. Moreover, APs provided less medical information, spoke less, and agreed more when interacting with a high-dominant compared to a low-dominant physician. They also talked more about emotions and were quicker in taking their turn to speak when interacting with a high-caring compared to a low-caring physician.

CONCLUSIONS

Dominant and caring physicians elicit different emotional and behavioral responses from APs. Physician dominance reduces patient engagement in the medical dialog and produces submissiveness, whereas physician caring increases patient emotionality.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Griffin SJ, Kinmonth AL, Veltman MW, Gillard S, Grant J, Stewart M. Effect on health-related outcomes of interventions to alter the interaction between patients and practitioners: a systematic review of trials. Annals of Family Medicine. 2004;2:595–608.

Hall JA, Roter DL, Katz NR. Meta-analysis of correlates of provider behavior in medical encounters. Med Care. 1988;26:657–75.

Roter DL, Hall JA. Doctors Talking with Patients/Patients Talking with Doctors: Improving Communication in Medical Visits. Westport: Auburn House; 2006.

Stewart MA. Effective physician–patient communication and health outcomes: a review. Can Med Assoc J. 1995;152:1423–33.

Krupat E, Yeager CM, Putnam S. Patient role orientations, doctor–patient fit, and visit satisfaction. Psychol Health. 2000;15:707–19.

Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196:129–36.

Buller MK, Buller DB. Physicians' communication style and patient satisfaction. J Health Soc Behav. 1987;28:375–88.

Emanuel EJ, Emanuel LL. Four models of the physician–patient relationship. J Am Med Assoc. 1992;267:2221–6.

Roter DL, Stewart M, Putnam SM, Lipkin M, Stiles W, Inui TS. Communication patterns of primary care physicians. J Am Med Assoc. 1997;277:350–6.

Schmid Mast M. Dominance and gender in the physician–patient interaction. Men’s Health & Gender. 2004;1:354–8.

Ben-Sira Z. Affective and instrumental components in the physician–patient relationship: an additional dimension of interaction theory. J Health Soc Behav. 1980;21:170–80.

Pascoe GC. Patient satisfaction in primary health care: a literature review and analysis. Eval Program Plann. 1983;6:185–210.

Roter DL, Frankel R, Hall JA, Sluyter D. The expression of emotion through nonverbal behavior in medical visits—mechanisms and outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:28–34.

Williams S, Weinman J, Dale J. Doctor–patient communication and patient satisfaction: a review. Fam Practice. 1998;15:480–92.

Cohen-Cole SA. The Medical Interview: The Three-Function Approach. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1991.

Burgoon JK, Pfau M, Parrott R, Birk T, Coker R, Burgoon M. Relational communication, satisfaction, compliance-gaining strategies, and compliance in communication between physicians and patients. Commun Monogr. 1987;54:307–23.

Speedling EJ, Rose DN. Building an effective doctor–patient relationship: from patient satisfaction to patient participation. Soc Sci Med. 1985;21:115–20.

Bertakis KD, Roter D, Putnam SM. The relationship of physician medical interview style to patient satisfaction. J Fam Pract. 1991;32:175–81.

Hall JA. Some observations on provider–patient communication research. Patient Educ Couns. 2003;50:9–12.

Blascovich J, Loomis J, Beall AC, Swinth KR, Hoyt CL, Bailenson JN. Immersive virtual environment technology: just another methodological tool for social psychology? Psychol Inq. 2002;13:146–49.

Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:371–83.

Schmid Mast M, Kindlimann A, Langewitz W. Patients' perception of bad news: how you put it really makes a difference. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;58:244–51.

Shapiro DE, Boggs SR, Melamed BG, Graham-Pole J. The effect of varied physician affect on recall, anxiety, and perceptions in women at risk for breast cancer: a simulated study. Health Psychol. 1992;11:61–6.

Schmid Mast M. Dominance as expressed and inferred through speaking time: a meta-analysis. Hum Commun Res. 2002;28:420–50.

Thimm C, Rademacher U, Kruse L. "Power-related talk". Control in verbal interaction. J Lang Soc Psychol. 1995;14:382–407.

Kimble CE, Olszewski DA. Gaze and emotional expression: the effects of message positivity-negativity and emotional intensity. J Res Pers. 1980;14:60–9.

Robinson JD. Getting down to business: talk, gaze, and body orientation during openings of doctor–patient consultations. Hum Commun Res. 1998;25:97–123.

Mehrabian A. Nonverbal communication. Chicago: Aldine; 1972.

Roter DL, Larson S. The Roter Interaction Analysis System (RIAS): utility and flexibility for analysis of medical interactions. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;46:243–51.

Schmid Mast M, Hall JA, Roter DL. Disentangling physician gender and physician communication style: their effects on patient satisfaction in a virtual medical visit. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68:16–22.

Tiedens LZ, Jimenez MC. Assimilation for affiliation and contrast for control: complementary self-construals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;85:1049–61.

Ambady N, LaPlante D, Nguyen T, Rosenthal R, Chaumeton N, Levinson W. Surgeons' tone of voice: a clue to malpractice history. Surgery. 2002;132:5–9.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the University of Zurich and by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (PP001-106528/1) to the first author. Parts of the data were presented at the International Conference on Communication in Healthcare 2006 in Basel, Switzerland. We thank Claudia Dietz, Nadine Steurer, Anja Barizzi, Andrea Luomajoki-Stierli, Nadja Abt, Evelyn Mosimann, and Florinda Zagaria for their help in data collection and coding. The virtual consultation room and the virtual physician were created through an Swiss National Science Foundation fellowship awarded to the first author.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

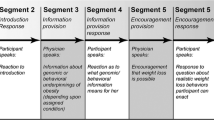

The following table displays the physician communication scripts varying in emotionality (high versus low) and in dominance (low versus high). The left side of the table shows the scripts for high emotionality and the right side of the table shows the scripts for the low emotionality. High and low emotionality each branch off on the right to low dominance and on the left to high dominance. The column in the middle indicates identical text for both low and high dominance conditions. The statements of the different conditions are on the same line.

ESM Table

(Doc 135 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schmid Mast, M., Hall, J.A. & Roter, D.L. Caring and Dominance Affect Participants’ Perceptions and Behaviors During a Virtual Medical Visit. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 523–527 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0512-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0512-5