Abstract

Background

Postmenopausal women with a prior fracture have an increased risk for future fracture. Whether a history of non-vertebral fracture defines a group of women with low bone mass but without osteoporosis for whom alendronate would prevent new non-vertebral fracture is not known.

Subjects and Methods

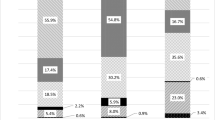

Secondary analysis of data from the Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT). Of 2,785 postmenopausal women with a T-score at the femoral neck between −1 and −2.5 and without prevalent radiographic vertebral deformity, 880 (31.6%) reported experiencing a fracture after 45 years of age. Women were randomized to placebo or alendronate (5 mg/day years for the first 2 years and 10 mg/day thereafter) and were followed for an average of 4.2 ± 0.5 years. Incident non-vertebral fractures were confirmed by x-rays and radiology reports.

Results

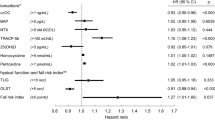

In the placebo arm, a self-report of prior fracture identified women with a 1.5-fold (hazard ratio [RH] 1.46, 95% C.I. 1.04–2.04) increased risk for incident non-vertebral fracture. However, there was no evidence that the effect of alendronate differed across subgroups of women with (RH 1.26 for alendronate vs placebo, 95% C.I. 0.89–1.79) and without prior fracture (RH 1.02 for alendronate vs placebo, 95% C.I. 0.76–1.38; P = 0.37 for interaction).

Conclusion

Assessing a clinical risk factor, prior non-vertebral fracture, did not identify women with low bone mass for whom alendronate reduced future non-vertebral fracture risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Looker AC, Orwoll ES, Johnston CC Jr, et al. Prevalence of low femoral bone density in older U.S. adults from NHANES III. J Bone Miner Res. 1997;12:1761–8.

Wainwright SA, Marshall LM, Ensrud KE, et al. Hip fracture in women without osteoporosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:2787–93.

Sanders KM, Pasco JA, Ugoni AM, et al. The exclusion of high trauma fractures may underestimate the prevalence of bone fragility fractures in the community. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1337–42.

Schuit SCE, van der Klift M, Weel AEAM, et al. Fracture incidence and association with bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Rotterdam Study. Bone. 2004;34:195–202.

Stone KL, Seeley DG, Lui L-Y, et al. BMD at multiple sites and risk of fractures of multiple types: long-term results from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2003;18:1947–54.

Siris ES, Chen YT, Abbott TA, et al. Bone mineral density thresholds for pharmacological intervention to prevent fractures. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1108–12.

Klotzbuecher CM, Ross PD, Landsman PB, Abbott TA III, Berger M. Patients with prior fracture have an increased risk of future fractures: a summary of the literature and statistical synthesis. J Bone Miner Res. 2000;15:721–39.

Cummings SR, Nevitt MC, Browner WS, et al. Risk factors for hip fracture in white women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:767–73.

Nguyen T, Sambrook P, Kelly P, et al. Prediction of osteoporotic fractures by postural instability and bone density. BMJ. 1993;307:1111–5.

Dargent-Molina P, Faviier F, Grandjean H, et al. Fall-related factors and risk of hip fracture: the EPIDOS prospective study. Lancet. 1996;348:145–9.

National Osteoporosis Foundation. Physician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 1998.

American Association of Clinical Endocrinology. Medical guidelines for clinical practice for the prevention and treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: 2001 edition, with selected updates from 2003. Endocrine Pract. 2003;9:544–64.

Siris ES, Genant HK, Laster AJ, et al. Enhanced prediction of fracture risk combining vertebral fracture status and BMD. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:761–70.

Ensrud KE, Black DM, Palermo L, et al. Treatment with alendronate prevents fractures in women at highest risk. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2614–7.

Quandt SA, Thompson DE, Schneider DL, et al. Effect of alendronate on vertebral fracture risk in women with bone mineral density T scores of −1.6 to −2.5 at the femoral neck: the Fracture Intervention Trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80:343–9.

Cummings SR, Black DM, Thompson DE, et al. Effect of alendronate on risk of fracture in women with low bone mineral density but without vertebral fractures. JAMA. 1998;280:2077–82.

Schousboe JT, Nyman JA, Kane RL, Ensrud KE. Cost-effectiveness of alendronate therapy for osteopenic postmenopausal women. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:734–41.

Schousboe JT, Ensrud KE, Nyman JA, et al. Potential cost-effective use of spine radiographs to detect vertebral deformity and select osteopenic post-menopausal women for amino-bisphosphonate therapy. Osteoporosis Int. 2005;16:1883–93.

McClung MR, Geusens P, Miller PD, et al. Effect of risedronate on the risk of hip fracture in elderly women. Hip Intervention Program Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:333–40.

Sornay-Rendu E, Munoz F, Garnero P, et al. Identification of osteopenic women at high risk of fracture: the OFELY study. J Bone Miner Res. 2005;20:1813–9.

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int. 2004;15:175–9.

Miller PD, Barlas S, Brenneman SK, et al. An approach to identifying osteopenic women at increased short-term risk of fracture. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:1113–20.

Black DM, Reiss TF, Nevitt MC, et al. Design of the fracture intervention trial. Osteoporos Int. 1993;3(suppl):3S29–S39.

Genant HK, Jergas M, van Kuijk C, eds. Vertebral Fracture in Osteoporosis. San Francisco, Calif: Radiology Research and Educational Foundation; 1995:131–147.

Harris ST, Watts NB, Genant HK, et al. Effects of risedronate treatment on vertebral and nonvertebral fractures in women with postmenopausal osteoporosis. JAMA. 1999;282:1344–52.

Reginster J, Minne HW, Sorensen OH, et al. Randomized trial of the effects of risedronate on vertebral fractures in women with established postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int. 2000;11:83–91.

Chestnut CH III, Skag A, Christiansen C, et al. Effects of oral ibandronate administered daily or intermittently on fracture risk in postmenopausal osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res. 2004;19:1241–9.

Neer RM, Arnaud CD, Zanchetta JR, et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1–34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1434–41.

Cauley JA, Robbins J, Chen Z, et al. Effects of estrogen plus progestin on risk of fracture and bone mineral density. the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1729–38.

Barrett-Connor E, Mosca L, Collins P, et al. Effects of raloxifene on cardiovascular events and breast cancer in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:125–37.

Lyles KW, Colon-Emeric CS, Magaziner JS, et al. Zoledronic acid and clinical fractures and mortality after hip fracture. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1799–1809.

Gallacher SJ, Gallagher AP, McQuillian C, et al. The prevalence of vertebral fracture amongst patients presenting with non-vertebral fractures. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:185–92.

Bauer DC, Garnero P, Hochberg MC, et al. Pretreatment levels of bone turnover and the antifracture efficacy of alendronate: the Fracture Intervention Trial. J Bone Miner Res. 2006;21:292–9.

Schousboe JT, Bauer DC, Nyman KA, et al. Potential for bone turnover markers to cost-effectively identify and select post-menopausal osteopenic women at high risk of fracture for bisphosphonate therapy. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:201–10.

Nevitt MC, Cummings SR, Browner WS, et al. The accuracy of self-report of fractures in elderly women: evidence from a prospective study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135:490–9.

Hundrup YA, Hoidrop S, Obel EB, Rasmussen NK. The validity of self-reported fractures among Danish female nurses: comparison with fractures registered in the Danish National Hospital Register. Scand J Pub Health. 2004;32:136–43.

Ivers RQ, Cummings RG, Mitchell P, Peduto AJ. The accuracy of self-reported fractures in older people. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:452–7.

Acknowledgments

This research was sponsored by Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, NJ.

Members of the Fracture Intervention Trial Research Group are listed in reference 23.

Authors’ contributions

Conception: KMR, SRC; Design: KMR, SRC, DCB, SS; analysis and interpretation: LP, KMR, SRC, DCB, KE; manuscript preparation: KMR, LP, SS, SRC, DCB, AF, JS, KE, AVS SRC

Sponsor role

Drafts of the manuscript were reviewed, and changes to the manuscript were recommended by all coauthors and staff at Merck. The final version of this manuscript was reviewed by all coauthors and the Fracture Intervention Trial Steering Committee; Merck Investigators constituted a minority of the steering committee. Merck Research Laboratories funded the original FIT study.

Lisa Palermo had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Conflict of Interest statement

KMR: prior research grant support from Eli Lilly; past speaker support from Proctor & Gamble. SRC: none; LP: none; SS: research grant support from Wyeth Pharmaceuticals; DCB: research funding from Merck Research Laboratories, Proctor and Gamble, Amgen, and Smith Kline Beecham; ACF: research grant support from Merck Research Laboratories, Amgen and Sanofi-Aventis; JTS: none; AVS: none; KE: none.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

This work is supported by K23 RR16047 and Merck Research Laboratories, Rahway, NJ.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ryder, K.M., Cummings, S.R., Palermo, L. et al. Does a History of Non-Vertebral Fracture Identify Women Without Osteoporosis for Treatment?. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 1177–1181 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0622-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0622-0