Abstract

Background

Primary care providers (PCPs) can play a critical role in helping patients receive the preventive health benefits of cancer genetic risk information. Thus, the objective of this systematic review was to identify studies of US PCPs’ knowledge, attitudes, and communication-related behaviors regarding genetic tests that could inform risk-stratification approaches for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screening in order to describe current findings and research gaps.

Methods

We conducted a systematic search of six electronic databases to identify peer-reviewed empirical articles relating to US PCPs and genetic testing for breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer published in English from 2008 to 2016. We reviewed these data and used narrative synthesis methods to integrate findings into a descriptive summary and identify research needs.

Results

We identified 27 relevant articles. Most focused on genetic testing for breast cancer (23/27) and colorectal cancer risk (12/27); only one study examined testing for prostate cancer risk. Most articles addressed descriptive research questions (24/27). Many studies (24/27) documented PCPs’ knowledge, often concluding that providers’ knowledge was incomplete. Studies commonly (11/27) examined PCPs’ attitudes. Across studies, PCPs expressed some concerns about ethical, legal, and social implications of testing. Attitudes about the utility of clinical genetic testing, including for targeted cancer screening, were generally favorable; PCPs were more skeptical of direct-to-consumer testing. Relatively fewer studies (9/27) examined PCPs’ communication practices regarding cancer genetic testing.

Discussion

This review indicates a need for investigators to move beyond descriptive research questions related to PCPs’ knowledge and attitudes about cancer genetic testing. Research is needed to address important gaps regarding the development, testing, and implementation of innovative interventions and educational programs that can improve PCPs’ genetic testing knowledge, assuage concerns about the appropriateness of cancer genetic testing, and promote open and effective patient-provider communication about genetic risk and genetic testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Genetic testing for individuals at hereditary risk for mutations in known cancer susceptibility genes is an important component of preventive medicine.1 , 2 Recommendations exist for the use of genetic testing to identify pathogenic variants in high-penetrance genes including BRCA1/2, associated with hereditary breast and ovarian cancer,3 – 5 and mismatch repair genes associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (i.e., Lynch syndrome).6 – 8 Such genetic testing can inform personalized cancer risk management strategies, including the use of cancer screening tests.

Although screening tests including mammography, colonoscopy, and sigmoidoscopy have established population-level health benefits,9 – 12 these tests also carry risks; as such, there is a desire to identify individuals who will derive the greatest benefit and least harm. Genetic testing for cancer susceptibility may have utility for risk stratification, thereby allowing for a more focused application of screening tests to those at greatest disease risk.13 – 16 For example, estimating an individual’s cancer risk based on genetic markers and traditional risk factors may lead to a more refined use of currently recommended screening tests (e.g., mammography).17 , 18 Information derived from genetic testing could also shift the balance of harms and benefits for some individuals such that screening tests like the PSA test, which is not recommended for the general population, may have utility in those with greatest genetic risk for prostate cancer.19 – 21 Those at higher genetic risk may also be candidates for more sensitive screening approaches (e.g., breast MRI).

For the promise of risk-stratified cancer screening to be realized, at-risk individuals will need to be identified and obtain genetic testing. Although nearly half of Americans are aware of genetic testing for cancer susceptibility,22 test use is low in the general population23 and among individuals with increased family history.24 Primary care providers (PCPs) play a critical role in addressing patients’ preventive healthcare needs and are in a position to assist patients with making informed decisions about the appropriate use of genetic testing. Prompted by patient inquiries or the collection and interpretation of family history data, PCPs can refer patients to genetic professionals for risk assessment and testing. Alternatively, PCPs can directly order genetic tests for patients, which may be particularly important when access to genetic professionals is limited. PCPs may also be tasked with interpreting the results of direct-to-consumer genetic tests purchased without physician involvement. Furthermore, PCPs can use patients’ genetic test results to inform recommendations for primary (e.g., prophylactic surgery, chemoprevention) and secondary (e.g., use and timing of screening tests) cancer prevention efforts.5 , 6

However, research suggests that PCPs may be unprepared for the task of helping patients gain access to benefits of cancer genetic risk information. According to a systematic review of studies regarding genetic services for common diseases including cancer published from 2000–2008,25 PCPs noted limitations in their knowledge about basic genetics and confidence in collecting and interpreting family history data, and generally felt underprepared for integrating genomic medicine into patient care. Similarly, a systematic review of research published from 2001–2012 concluded that a lack of knowledge and skills, along with attitudes and concerns about patient distress, were common barriers to PCPs integrating genetic services into patient management.26 This past work confirms that PCPs’ knowledge and attitudes are critical to their genetic testing utilization.

With the present study, we sought to describe US PCPs’ knowledge, attitudes, and communication-related behaviors regarding genetic tests that could inform risk-stratification approaches for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer screening. To inform a future research agenda in this area, we aimed to both describe the scope of research questions addressed in past studies and summarize their findings. For this review, we defined knowledge as PCPs’ level of subjective or objective understanding about genetic services; basic genetic concepts; treatment and management options for patients with genetic mutations; and their self-efficacy, confidence, and comfort in discussing genetic testing with patients. Attitudes included PCPs’ personal opinions or views about topics including the validity or utility of clinical and direct-to-consumer genetic tests for hereditary cancer risk; incorporation of genetic testing into practice; and ethical, legal, or social implications of testing for patients. Communication-related behaviors reflected the extent, frequency, and outcomes of PCPs’ discussions of genetic testing for cancer risk with patients. We limited the review to genetic testing related to breast, colorectal, and prostate cancer because these represent cancers of high incidence and mortality,27 and for which genetic information may be particularly useful in risk-stratification decisions for the frequency and/or modality of screening tests.13 – 15 , 28

Methods

Literature search

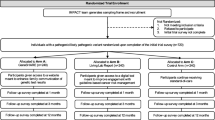

A health science librarian (MLF) comprehensively searched six databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CINAHL, Cochrane Library) to identify peer-reviewed articles relating to PCPs and genetic testing for breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer. The search strategy was developed to retrieve articles assessing PCP knowledge; attitudes; provider- or patient-initiated discussions of genetic testing; referral behaviors; and interventions to improve these domains (for details see Figure 1 and Online Appendix 1). Additional articles were identified through searching reference lists of selected papers.

PRISMA flow diagram describing the literature search and record review process for the present study. *PubMed was searched on September 5, 2016, using MeSH terms and title/abstract search; †EMBASE was searched on August 3, 2016, using a combination of EMTREE and title/abstract search; ‡Web of Science and Cochrane Library were searched on August 3, 2016, using keyword search; §PsycINFO was searched on August 13, 2016, using keyword search; ǁCINAHL was searched on August 18, 2016, using a combination of CINAHL headings and keyword search

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they addressed genetic testing related to breast, colorectal, or prostate cancer and involved PCPs (operationalized as internists, family practitioners, obstetrician/gynecologists, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, consistent with IOM29 and CMS30 definitions). Studies involving other provider types were included if relevant outcomes for PCPs were reported separately and/or if PCPs represented a majority of the sample. Studies were limited to English-language articles set in the US and published from January 2008 (the last year of data included in a related systematic review25)–August 2016 in peer-reviewed journals, excluding commentaries, editorials, proceedings, dissertations, book reviews, and meeting abstracts. Gray literature was not searched.

Record review

The combined searches produced 2377 results (Fig. 1). After removing duplicates, one team member reviewed the remaining 1822 records and excluded 1725 based on irrelevant article titles and abstracts (e.g., bench science studies, international data). Another team member verified these decisions. Two team members screened the full texts of the remaining 97 articles, eliminating an additional 55 that did not address genetic testing or a cancer of interest.

Article audit

Five team members double-coded the full text of the remaining 42 articles using an audit form and data dictionary developed for this review (Online Appendix 2), and they determined that 15 articles did not meet the study criteria. Team members coded the final 27 articles for provider type; cancer type; data source (e.g., survey); and PCPs’ knowledge, attitudes, and communication-related behaviors. Relevant research questions, measurement approaches, and results were documented. Coding differences were discussed and reconciled by coding pairs; when disagreement arose, final decisions were reached by group consensus. The team reviewed these data and used narrative synthesis methods to integrate findings into a descriptive summary.

Results

Table 1 shows characteristics of the reviewed studies; Table 2 summarizes the research questions, methods, and relevant outcomes of each study. Most commonly, studies included family practitioners (n = 17), internists (n = 14), and obstetricians/gynecologists (n = 12), with sample sizes ranging from 7–1500 participants. Studies focused on genetic testing for breast (n = 23) and colorectal cancer risk (n = 12); only one study examined testing for prostate cancer risk. Surveys were the most commonly used data collection method (n = 21), and a minority of studies (n = 3) evaluated an intervention.

Knowledge of genetic tests for cancer risk

We identified 24 (of 27) articles addressing research questions relevant to PCPs’ knowledge.33 – 53 , 55 , 56 , 58 Of these, 13 studies evaluated PCPs’ objective knowledge.34 , 35 , 38 , 39 , 41 , 42 , 44 , 47 – 50 , 55 , 58 In seven studies, objective knowledge was assessed with a survey utilizing a scale or test to measure accurate understanding of basic genetic principles, clinical practice guidelines, and/or features of hereditary cancer syndromes.35 , 38 , 39 , 42 , 47 , 48 , 50 In the other six studies, case scenarios or standardized patients were used to measure PCPs’ abilities to identify high-risk patients and appropriate genetic testing situations.32 , 34 , 41 , 44 , 49 , 55 Aside from articles reporting on the same sample,38 , 48 there was no overlap in measures. Across these studies, PCPs were reported to have incomplete or inaccurate knowledge about the inheritance and characteristics of hereditary cancer syndromes and interpretation of genetic test results. For instance, in a cross-sectional survey of 176 family practitioners, the modal score on a 10-point scale of factual hereditary breast and colorectal cancer knowledge was 6, with none of the sample accurately answering all items.42 In addition, three studies examined objective knowledge pertaining to legal genetic discrimination protections.39 , 44 , 53 Knowledge in this domain was concluded to be suboptimal; for instance, in a cross-sectional survey of 1120 family practitioners and internists, 9% had accurate knowledge about legal insurance protections related to genetic test results.53

Ten studies examined PCPs’ self-reported subjective or perceived knowledge.33 , 37 , 42 – 45 , 47 , 50 , 51 , 55 Although there was no overlap in measures, studies consistently reported a lack of PCPs’ confidence in their genetic testing-related knowledge. For example, in a cross-sectional survey of 1311 family practitioners, 54% were not confident in their knowledge of genetic testing in primary care including testing for breast cancer risk.45 In another cross-sectional survey of 1209 Oregon clinicians, 83% of primary care providers and 76% of obstetricians/gynecologists reported that they were “not at all” or “somewhat” (vs. “moderately” or “very”) confident in their knowledge of colorectal cancer genetics.37 Seven studies also evaluated PCPs’ knowledge in terms of their comfort level with discussing aspects of cancer genetic testing with patients,33 , 40 , 43 , 44 , 46 , 53 , 56 with results suggesting that PCPs rarely felt prepared for the task of counseling patients about genetic testing. For example, a survey of 50 obstetricians/gynecologists found that 74% did not feel comfortable counseling patients about available genetic testing for Lynch syndrome, and 76% did not feel comfortable counseling patients about such testing criteria.40

One study evaluated an intervention designed to influence PCPs’ genetic testing knowledge and clinical behaviors.52 Scheuner and colleagues used a mixed-method study design and medical record abstraction to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a multicomponent cancer genetics toolkit in the context of women’s primary care clinics at a Veterans Administration medical center. Among seven primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants, toolkit use improved knowledge about cancer genetics [mean total correct responses increased from 59% (range: 26%–77%) pre-implementation to 73% (range: 52%–90%) post-implementation].

Attitudes regarding genetic tests for cancer risk

We identified 11 (of 27) articles including research questions regarding PCPs’ attitudes.33 , 34 , 41 – 45 , 51 , 52 , 55 , 56 Of these, five studies examined PCPs’ views about ethical, legal, or social implications of testing.33 , 41 , 43 , 44 , 55 These studies noted varying beliefs about the effect of genetic testing on patients’ anxiety. Specifically, whereas a cross-sectional survey of 351 family practitioners, internists, and obstetrician/gynecologists found that only 14% of respondents believed that information about breast cancer risk creates unnecessary anxiety for many women,41 a mixed-method assessment of 24 family practitioners, urologists, and urology residents found that 74% of participants were concerned that increased-risk results could unnecessarily increase patient anxiety.33 Concerns about privacy issues and discrimination were also documented; for instance, a cross-sectional survey of 220 family practitioners and internists found that 27% were “very concerned” about genetic privacy,43 and qualitative data collected from 24 family practitioners, urologists, and urology residents highlighted concerns that test results could put patients at risk for discrimination by insurance companies and employers.33 Furthermore, a cross-sectional survey featuring a vignette of a hypothetical low-risk patient found that among 284 family physicians, 65% believed that refusing to refer the patient to genetic services would harm the provider-patient relationship.55

Three studies evaluated PCPs’ perceptions regarding the validity or utility of clinical genetic tests, all in the context of breast cancer risk.34 , 41 , 45 One reported on coded interactions between 86 family practitioners and internists with standardized patients and noted that many providers expressed skepticism about the value of genetic testing.34 Through the analysis of survey items, the other studies reported predominantly positive provider opinions about the accuracy and health benefits of genetic testing.41 , 45 Two studies examined PCPs’ perceptions regarding the validity and utility of direct-to-consumer tests for cancer risk, documenting generally unfavorable attitudes.33 , 45 For example, a cross-sectional survey of 1311 family practitioners found that 58% of participants believed this testing would do more harm than good for patients.45

Five studies investigated PCPs’ attitudes about the implications of genetic tests for cancer screening and other risk management behaviors.33 , 41 , 44 , 51 , 56 For instance, consistent with the goals of risk-stratified cancer screening, 65% of 1181 surveyed non-genetics providers agreed that genetic testing may reduce unnecessary cancer screening.44 Similarly, a mixed-method assessment of 24 family practitioners, urologists, and urology residents found that 86% believed direct-to-consumer genomic testing could inform the age at which to start prostate cancer screening and 76% believed such testing could inform screening frequency.33 A cross-sectional survey of 156 PCPs also found that 78% of participants perceived that it is very important to know about genetic counseling and testing for cancer survivors in order to identify high-risk individuals who could benefit from more comprehensive surveillance.51

Communication-related behaviors regarding genetic tests for cancer risk

We identified 9 (of 27) articles examining aspects of provider-patient communication.31 , 33 , 34 , 39 , 41 , 45 , 52 , 54 , 57 Of these, four studies provided descriptive information about PCPs’ experiences discussing genetic risk and testing (2 relying on surveys in the breast cancer context41 , 45 and 1 using mixed-methods in the prostate cancer context33). The other used a novel study design featuring standardized patients to evaluate communication behaviors among 86 providers and found that in only 21% and 3% of encounters did providers express opinions suggesting that patients at high maternal or paternal breast cancer risk, respectively, were candidates for genetic testing.34 Two additional studies used cross-sectional surveys to assess the extent to which PCPs adhered to clinical guidelines in discussions about consenting to hereditary breast and ovarian cancer testing39 , 54 and observed that many were non-adherent (e.g., among 81 providers, 39% did not always discuss implications for family, and 64% did not always discuss the possibility of another hereditary cancer syndrome54). Furthermore, two studies reported limited instances of discussions between PCPs and patients regarding direct-to-consumer testing (e.g., with 71%45 to 92%33 of providers not having had a patient ask questions about direct-to-consumer testing).

Three studies involved the use of interventions designed to influence PCPs’ communication behaviors.31 , 52 , 57 For instance, as noted, Scheuner and colleagues evaluated a multicomponent cancer genetics toolkit targeted at providers that improved their discussion and documentation of cancer family history and appropriate patient referrals for genetic consultation.52 Another study evaluated an educational intervention among 121 primary care physicians and found that some communication behaviors improved (e.g., 78% of intervention physicians explored genetic counseling benefits with a standardized patient versus 61% of controls); however, the intervention did not lead to significant differences in the offering of a genetic counseling referral or recommending of genetic testing.31

Discussion

PCPs represent the front line of screening for inherited disease risks and are increasingly involved in delivering genetic services.59 – 61 As gatekeepers, PCPs need to know how to interpret genetic test results, understand when to refer and ask for second opinions of genetic professionals,59 , 62 , 63 and address complex personal, cultural, ethical, legal, and social issues associated with genetic testing.59

This review confirmed relatively low levels of objective and subjective genetic testing-related knowledge among PCPs. Such trends have serious implications for the integration of genetic testing technologies into routine patient care; feeling unqualified to manage tasks surrounding test ordering and counseling46 and uncertain about guidelines43 inhibits PCPs’ genetic test adoption. Although basic genetic knowledge appears to be stronger among younger, more recent medical graduates, specialists, and providers in academic medical centers,25 , 64 there is a clear need for educational interventions that can improve genetics-related knowledge among all PCPs. Evidence suggests that PCPs are generally open to additional genetics education, such as brief training programs that contain continuing web-based education modules accessible outside of a classroom.38 , 43 Opportunities to develop skills to interpret genetic tests and understand how to maintain genetic privacy and confidentiality appear to be of interest to these providers.43 Furthermore, access to clearinghouses that provide a comprehensive listing of available tests, information on test sensitivity and specificity, the pros and cons of testing for specific conditions, and professional society guidelines would enhance PCPs’ ability to keep up with developments in genetic testing65 and address the challenge of understanding which tests are worth doing on which patients. Such knowledge will be vital for PCPs as genetic testing approaches and decisions become more complex (for instance, as reflected in the complexity of ordering and interpreting multi-gene panel tests, which are cost-effective, efficient tests that allow for the simultaneous analysis of numerous moderate- and high-penetrance cancer susceptibility genes66).

Across studies, there was substantial variation in the measures used to assess objective genetic testing-related knowledge. This suggests a need for future research to develop validated, standardized measures that assess critical factual knowledge necessary for PCPs to integrate genetic testing into patient management. Such measures may reflect knowledge related to core competencies (e.g., principles of Mendelian inheritance, characteristics of high-risk family histories) and professional society guidelines regarding testing. Data from these measures could be coupled with patient-level data (derived from electronic health records and learning health systems67) to assess the efficacy of provider-directed educational interventions in improving knowledge and testing-related behaviors.

PCPs’ attitudes, driven by beliefs about test validity or clinical utility, are complex and evolving. Although genetic testing may have value for risk stratification, some skepticism exists among PCPs;34 such skepticism may be ameliorated through future research aimed at improving provider knowledge and developing clinical decision support tools to guide providers to order the correct tests and use genetic data for patient management. Two of the reviewed studies also found generally unfavorable attitudes regarding the utility of direct-to-consumer genetic tests.33 , 45 As public awareness and use of direct-to-consumer testing grows,68 , 69 PCPs are likely to be confronted with patients seeking clarity, interpretation, or reassurance about these results.70 , 71 Research is needed to develop and evaluate educational and communication interventions that prepare PCPs to navigate these situations and to help their patients recognize the limitations of these tests.71 – 73

We identified fewer studies examining aspects of communication. Yet, because of their influential role, PCPs will need to address the complexities of risk communication in the genomics era. Ideally genetic professionals will offer genetic counseling; however, the need to provide referrals, supplement limited access to genetic professionals, and integrate genetic risk information into the holistic care of a patient will nonetheless require PCPs to collect a detailed family history and discuss nuanced aspects of individual risk with patients (e.g., the incremental risk for chronic disease attributable to genetic versus behavioral factors).74

Research to develop and test innovative communication-focused interventions is warranted. Consistent with suggestions from IOM,75 PCPs may benefit from training that includes opportunities to directly learn about communication preferences from patients with an inherited predisposition to disease. To evaluate these programs, researchers should assess the perspectives of PCPs and their patients along with patient-level care delivery (e.g., satisfaction) and health outcomes (e.g., knowledge, adherence to appropriate screening tests). PCPs could benefit from genetics-related electronic health record tools, and those in community settings could particularly benefit from a team-based approach that includes assistance of a genetic professional trained in risk assessment and communication. Future research to evaluate technology-based approaches that extend the reach of a limited genetics workforce, such as telegenetics,76 , 77 telephone counseling,78 , 79 and web-based case conferencing,80 may address this need.

Limitations

Although we used a comprehensive search strategy, all relevant literature may not have been captured in this review. We aimed to focus on genetic testing for breast, colorectal, and prostate cancers; however, the vast majority of identified studies addressed BRCA1/2 testing, and we did not examine potential differences in outcomes across cancer types. Future studies will need to assess PCPs’ experiences with more diverse forms of genetic testing. Furthermore, this review focused predominantly on broad research trends and gaps from the perspective of PCPs, thereby not addressing patient perspectives, social factors (e.g., racism), or healthcare system factors (e.g., clinical decision support) that can influence care delivery.81 This review did not focus on how provider characteristics (e.g., training, age) may contribute to differences in the outcomes of interest; future research could explore such differences. Finally, this review does not offer insight into PCPs’ experiences with novel applications of genomic testing currently being introduced into cancer care (e.g., multi-gene panel testing, although a reviewed article noted that 42% of providers have ordered such testing39).

Conclusions

We have found a need to move beyond research questions related to describing PCPs’ cancer genetic knowledge and attitudes about the utility of testing. Important knowledge gaps exist in the development, evaluation, and implementation of interventions and educational programs designed to improve PCPs’ understanding of fundamental genetic principles, genetic test characteristics, and professional guidelines regarding testing; assuage PCPs’ concerns about clinical, ethical, legal, and social implications of testing; and promote open and effective communication about genetic risk and testing. Interventions and programs that capitalize on innovative methods for reaching and engaging PCPs and that allow them to gain access to and develop partnerships with genetic professionals are needed. Such efforts could ultimately help PCPs to embrace genomics into their practices and effectively address their patients’ preventive health needs.

References

Garber JE, Offit K. Hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(2):276–92.

Weitzel JN, Blazer KR, Macdonald DJ, Culver JO, Offit K. Genetics, genomics, and cancer risk assessment: state of the art and future directions in the era of personalized medicine. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:327–59.

Nelson HD, Pappas M, Zakher B, Mitchell JP, Okinaka-Hu L, Fu R. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: a systematic review to update the US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):255–66.

Moyer VA. Risk assessment, genetic counseling, and genetic testing for BRCA-related cancer in women: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):271–81.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): genetic/familial high-risk assessment: breast and ovarian, version 1.2017. Fort Washington: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; 2016. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_screening.pdf. Accessed 17 Nov 2016.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology (NCCN guidelines): genetic/familial high-risk assessment: colorectal, version 2.2016. Fort Washington: National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; 2016. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/genetics_colon.pdf. Accessed 17 Nov 2016.

Evaluation of Genomic Applications in Practice and Prevention (EGAPP) Working Group. Recommendations from the EGAPP Working Group: genetic testing strategies in newly diagnosed individuals with colorectal cancer aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome in relatives. Genet Med. 2009;11(1):35–41.

Palomaki GE, McClain MR, Melillo S, Hampel HL, Thibodeau SN. EGAPP supplementary evidence review: DNA testing strategies aimed at reducing morbidity and mortality from Lynch syndrome. Genet Med. 2009;11(1):42–65.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–26. w-236.

Nelson HD, Tyne K, Naik A, Bougatsos C, Chan BK, Humphrey L. Screening for breast cancer: an update for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):727–37. w237-742.

Whitlock EP, Lin JS, Liles E, Beil TL, Fu R. Screening for colorectal cancer: a targeted, updated systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):638–58.

US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for colorectal cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(9):627–37.

Pashayan N, Duffy SW, Chowdhury S, et al. Polygenic susceptibility to prostate and breast cancer: implications for personalised screening. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(10):1656–63.

Chowdhury S, Dent T, Pashayan N, et al. Incorporating genomics into breast and prostate cancer screening: assessing the implications. Genet Med. 2013;15(6):423–32.

Khoury MJ, Janssens AC, Ransohoff DF. How can polygenic inheritance be used in population screening for common diseases? Genet Med. 2013;15(6):437–43.

Burton H, Chowdhury S, Dent T, Hall A, Pashayan N, Pharoah P. Public health implications from COGS and potential for risk stratification and screening. Nat Genet. 2013;45(4):349–51.

Mavaddat N, Pharoah PD, Michailidou K, et al. Prediction of breast cancer risk based on profiling with common genetic variants. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107(5):djv036.

Sieh W, Rothstein JH, McGuire V, Whittemore AS. The role of genome sequencing in personalized breast cancer prevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2014;23(11):2322–7.

Moyer VA. Screening for prostate cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(2):120–34.

Chou R, Croswell JM, Dana T, et al. Screening for prostate cancer: a review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(11):762–71.

Pashayan N, Duffy SW, Neal DE, et al. Implications of polygenic risk-stratified screening for prostate cancer on overdiagnosis. Genet Med. 2015;17(10):789–95.

Mai PL, Vadaparampil ST, Breen N, McNeel TS, Wideroff L, Graubard BI. Awareness of cancer susceptibility genetic testing: the 2000, 2005, and 2010 National Health Interview Surveys. Am J Prev Med. 2014;46(5):440–8.

Taber JM, Chang CQ, Lam TK, Gillanders EM, Hamilton JG, Schully SD. Prevalence and correlates of receiving and sharing high-penetrance cancer genetic test results: findings from the Health Information National Trends Survey. Public Health Genomics. 2015;18(2):67–77.

Baer HJ, Brawarsky P, Murray MF, Haas JS. Familial risk of cancer and knowledge and use of genetic testing. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(7):717–24.

Scheuner MT, Sieverding P, Shekelle PG. Delivery of genomic medicine for common chronic adult diseases a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;299(11):1320–34.

Mikat-Stevens NA, Larson IA, Tarini BA. Primary-care providers’ perceived barriers to integration of genetics services: a systematic review of the literature. Genet Med. 2015;17(3):169–76.

Smith RA, Manassaram-Baptiste D, Brooks D, et al. Cancer screening in the United States, 2015: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and current issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65(1):30–54.

Avital I, Langan RC, Summers TA, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for precision risk stratification-based screening (PRSBS) for colorectal cancer: lessons learned from the US Armed Forces: Consensus and future directions. J Cancer. 2013;4(3):172–92.

Institute of Medicine. Defining primary care. In: Primary care: America’s health in a new era Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1996.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Glossary. Baltimore, MD. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/apps/glossary/search.asp?Term=primary+care&Language=English&SubmitTermSrch=Search. Accessed 17 Nov 2016.

Bell RA, McDermott H, Fancher TL, Green MJ, Day FC, Wilkes MS. Impact of a randomized controlled educational trial to improve physician practice behaviors around screening for inherited breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):334–41.

Bellcross CA, Leadbetter S, Alford SH, Peipins LA. Prevalence and healthcare actions of women in a large health system with a family history meeting the 2005 USPSTF recommendation for BRCA genetic counseling referral. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013;22(4):728–35.

Birmingham WC, Agarwal N, Kohlmann W, et al. Patient and provider attitudes toward genomic testing for prostate cancer susceptibility: a mixed method study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:279.

Burke W, Culver J, Pinsky L, et al. Genetic assessment of breast cancer risk in primary care practice. Am J Med Genet A. 2009;149a(3):349–56.

Chan V, Blazey W, Tegay D, et al. Impact of academic affiliation and training on knowledge of hereditary colorectal cancer. Public Health Genomics. 2014;17(2):76–83.

Cohn J, Blazey W, Tegay D, et al. Physician risk assessment knowledge regarding BRCA genetics testing. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(3):573–9.

Cox SL, Zlot AI, Silvey K, et al. Patterns of cancer genetic testing: a randomized survey of Oregon clinicians. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;2012:294730.

Cragun D, Besharat AD, Lewis C, Vadaparampil ST, Pal T. Educational needs and preferred methods of learning among Florida practitioners who order genetic testing for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(4):690–7.

Cragun D, Scherr C, Camperlengo L, Vadaparampil ST, Pal T. Evolution of hereditary breast cancer genetic services: are changes reflected in the knowledge and clinical practices of Florida providers? Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2016;20(10):569–78.

Frey MK, Taylor JS, Pauk SJ, et al. Knowledge of Lynch syndrome among obstetrician/gynecologists and general surgeons. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014;126(2):161–4.

Guerra CE, Sherman M, Armstrong K. Diffusion of breast cancer risk assessment in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(3):272–9.

Kelly KM, Love MM, Pearce KA, Porter K, Barron MA, Andrykowski M. Cancer risk assessment by rural and Appalachian family medicine physicians. J Rural Health. 2009;25(4):372–7.

Klitzman R, Chung W, Marder K, et al. Attitudes and practices among internists concerning genetic testing. J Genet Couns. 2013;22(1):90–100.

Lowstuter KJ, Sand S, Blazer KR, et al. Influence of genetic discrimination perceptions and knowledge on cancer genetics referral practice among clinicians. Genet Med. 2008;10(9):691–8.

Mainous AG 3rd, Johnson SP, Chirina S, Baker R. Academic family physicians’ perception of genetic testing and integration into practice: a CERA study. Fam Med. 2013;45(4):257–62.

Menzin AW, Anderson BL, Williams SB, Schulkin J. Education and experience with breast health maintenance and breast cancer care: a study of obstetricians and gynecologists. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(1):87–91.

Nair N, Bellcross C, Haddad L, et al. Georgia primary care providers’ knowledge of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer syndrome. J Cancer Educ. 2015. doi:10.1007/s13187-015-0950-9.

Pal T, Cragun D, Lewis C, et al. A statewide survey of practitioners to assess knowledge and clinical practices regarding hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers. 2013;17(5):367–75.

Plon SE, Cooper HP, Parks B, et al. Genetic testing and cancer risk management recommendations by physicians for at-risk relatives. Genet Med. 2011;13(2):148–54.

Ready KJ, Daniels MS, Sun CC, Peterson SK, Northrup H, Lu KH. Obstetrics/gynecology residents’ knowledge of hereditary breast and ovarian cancer and Lynch syndrome. J Cancer Educ. 2010;25(3):401–4.

Salz T, Oeffinger KC, Lewis PR, Williams RL, Rhyne RL, Yeazel MW. Primary care providers’ needs and preferences for information about colorectal cancer survivorship care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(5):635–51.

Scheuner MT, Hamilton AB, Peredo J, et al. A cancer genetics toolkit improves access to genetic services through documentation and use of the family history by primary-care clinicians. Genet Med. 2014;16(1):60–9.

Shields AE, Burke W, Levy DE. Differential use of available genetic tests among primary care physicians in the United States: results of a national survey. Genet Med. 2008;10(6):404–14.

Vadaparampil ST, Scherr CL, Cragun D, Malo TL, Pal T. Pre-test genetic counseling services for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer delivered by non-genetics professionals in the state of Florida. Clin Genet. 2015;87(5):473–7.

White DB, Bonham VL, Jenkins J, Stevens N, McBride CM. Too many referrals of low-risk women for BRCA1/2 genetic services by family physicians. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17(11):2980–6.

Wood ME, Flynn BS, Stockdale A. Primary care physician management, referral, and relations with specialists concerning patients at risk for cancer due to family history. Public Health Genomics. 2013;16(3):75–82.

Zazove P, Plegue MA, Uhlmann WR, Ruffin MT. Prompting primary care providers about increased patient risk as a result of family history: does it work? J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(3):334–42.

Bellcross CA, Kolor K, Goddard KA, Coates RJ, Reyes M, Khoury MJ. Awareness and utilization of BRCA1/2 testing among US primary care physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(1):61–6.

American College of Preventive Medicine. Genetic testing clinical reference for clinicians. Available at: http://www.acpm.org/?GeneticTestgClinRef. Accessed 17 Nov 2016

Blaine SM, Carroll JC, Rideout AL, et al. Interactive genetic counseling role-play: a novel educational strategy for family physicians. J Genet Couns. 2008;17(2):189–95.

Gramling R, Clarke J, Simmons E. Racial distribution of patient population and family physician endorsed importance of screening patients for inherited predisposition to cancer. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(1):50–4.

Engstrom JL, Sefton MG, Matheson JK, Healy KM. Genetic competencies essential for health care professionals in primary care. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2005;50(3):177–83.

Shirts BH, Parker LS. Changing interpretations, stable genes: Responsibilities of patients, professionals, and policy makers in the clinical interpretation of complex genetic information. Genet Med. 2008;10(11):778–83.

Hall MJ, Forman AD, Montgomery SV, Rainey KL, Daly MB. Understanding patient and provider perceptions and expectations of genomic medicine. J Surg Oncol. 2015;111(1):9–17.

Trinidad SB, Fryer-Edwards K, Crest A, Kyler P, Lloyd-Puryear MA, Burke W. Educational needs in genetic medicine: primary care perspectives. Community Genet. 2008;11(3):160–5.

Domchek SM, Bradbury A, Garber JE, Offit K, Robson ME. Multiplex genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: out on the high wire without a net? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(10):1267–70.

Friedman CP, Wong AK, Blumenthal D. Achieving a nationwide learning health system. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(57):57cm29.

Finney Rutten LJ, Gollust SE, Naveed S, Moser RP. Increasing public awareness of direct-to-consumer genetic tests: health care access, Internet use, and population density correlates. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2012;2012:309109.

Agurs-Collins T, Ferrer R, Ottenbacher A, Waters EA, O’Connell ME, Hamilton JG. Public awareness of direct-to-consumer genetic tests: findings from the 2013 US Health Information National Trends Survey. J Cancer Educ. 2015;30(4):799–807.

McGuire AL, Burke W. An unwelcome side effect of direct-to-consumer personal genome testing: raiding the medical commons. JAMA. 2008;300(22):2669–71.

Bloss CS, Darst BF, Topol EJ, Schork NJ. Direct-to-consumer personalized genomic testing. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20(R2):R132–41.

Eng C, Sharp RR. Bioethical and clinical dilemmas of direct-to-consumer personal genomic testing: the problem of misattributed equivalence. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2(17):17cm15.

Ng PC, Murray SS, Levy S, Venter JC. An agenda for personalized medicine. Nature. 2009;461(7265):724–6.

Amara N, Blouin-Bougie J, Jbilou J, Halilem N, Simard J, Landry R. The knowledge value-chain of genetic counseling for breast cancer: an empirical assessment of prediction and communication processes. Familial Cancer. 2016;15(1):1–17.

Institute of Medicine. Improving genetics education in graduate and continuing health professional education: workshop summary. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2015.

Hilgart JS, Hayward JA, Coles B, Iredale R. Telegenetics: a systematic review of telemedicine in genetics services. Genet Med. 2012;14(9):765–76.

Bradbury A, Patrick-Miller L, Harris D, et al. Utilizing remote real-time videoconferencing to expand access to cancer genetic services in community practices: a multicenter feasibility study. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(2):e23.

Kinney AY, Butler KM, Schwartz MD, et al. Expanding access to BRCA1/2 genetic counseling with telephone delivery: a cluster randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106(12):dju328.

Schwartz MD, Valdimarsdottir HB, Peshkin BN, et al. Randomized noninferiority trial of telephone versus in-person genetic counseling for hereditary breast and ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(7):618–26.

Blazer KR, Christie C, Uman G, Weitzel JN. Impact of web-based case conferencing on cancer genetics training outcomes for community-based clinicians. J Cancer Educ. 2012;27(2):217–25.

Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Introduction: understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(44):2–10.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Hamilton was supported by HHSN261201400046M, HHSN261201600149M and NCI P30 CA008748. Dr. Edwards was employed by Leidos Biomedical Research Inc. as a contractor supporting the National Cancer Institute. Dr. Edwards is currently employed by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Ms. Abdiwahab was a Cancer Research Training Award Fellow at the National Cancer Institute and is currently a doctoral student at the University of California San Francisco. Mr. Jdayani was an Introduction to Cancer Research Careers Fellow at the National Cancer Institute and is currently employed by Torrance Memorial Health System. The funders had no direct role in study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 48 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hamilton, J.G., Abdiwahab, E., Edwards, H.M. et al. Primary care providers’ cancer genetic testing-related knowledge, attitudes, and communication behaviors: A systematic review and research agenda. J GEN INTERN MED 32, 315–324 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3943-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3943-4