-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Karl Swedberg, John Cleland, Henry Dargie, Helmut Drexler, Ferenc Follath, Michel Komajda, Luigi Tavazzi, Otto A. Smiseth, Antonello Gavazzi, Axel Haverich, Arno Hoes, Tiny Jaarsma, Jerzy Korewicki, Samuel Lévy, Cecilia Linde, José-Luis Lopez-Sendon, Markku S. Nieminen, Luc Piérard, Willem J. Remme, Authors/Task Force Members, Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic heart failure: executive summary (update 2005): The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Heart Failure of the European Society of Cardiology, European Heart Journal, Volume 26, Issue 11, June 2005, Pages 1115–1140, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehi204

Close - Share Icon Share

ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG), Silvia G. Priori (Chairperson) (Italy), Jean-Jacques Blanc (France), Andrzej Budaj (Poland), John Camm (UK), Veronica Dean (France), Jaap Deckers (The Netherlands), Kenneth Dickstein (Norway), John Lekakis (Greece), Keith McGregor (France), Marco Metra (Italy), João Morais (Portugal), Ady Osterspey (Germany), Juan Tamargo (Spain), José Luis Zamorano (Spain) Document Reviewers, Marco Metra (CPG Review Coordinator) (Italy), Michael Böhm (Germany), Alain Cohen-Solal (France), Martin Cowie (UK), Ulf Dahlström (Sweden), Kenneth Dickstein (Norway), Gerasimos S. Filippatos (Greece), Edoardo Gronda (Italy), Richard Hobbs (UK), John K. Kjekshus (Norway), John McMurray (UK), Lars Rydén (Sweden), Gianfranco Sinagra (Italy), Juan Tamargo (Spain), Michal Tendera (Poland), Dirk van Veldhuisen (The Netherlands), Faiez Zannad (France)

Preamble

Guidelines and Expert Consensus Documents aim to present all the relevant evidence on a particular issue in order to help physicians to weigh the benefits and risks of a particular diagnostic or therapeutic procedure. They should be helpful in everyday clinical decision-making.

A great number of Guidelines and Expert Consensus Documents have been issued in recent years by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and by different organizations and other related societies. This profusion can put at stake the authority and validity of guidelines, which can only be guaranteed if they have been developed by an unquestionable decision-making process. This is one of the reasons why the ESC and others have issued recommendations for formulating and issuing Guidelines and Expert Consensus Documents.

In spite of the fact that standards for issuing good quality Guidelines and Expert Consensus Documents are well defined, recent surveys of Guidelines and Expert Consensus Documents published in peer-reviewed journals between 1985 and 1998 have shown that methodological standards were not complied with in the vast majority of cases. It is therefore of great importance that guidelines and recommendations are presented in formats that are easily interpreted. Subsequently, their implementation programmes must also be well conducted. Attempts have been made to determine whether guidelines improve the quality of clinical practice and the utilization of health resources.

The ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG) supervises and coordinates the preparation of new Guidelines and Expert Consensus Documents produced by Task Forces, expert groups, or consensus panels. The chosen experts in these writing panels are asked to provide disclosure statements of all relationships they may have which might be perceived as real or potential conflicts of interest. These disclosure forms are kept on file at the European Heart House, headquarters of the ESC. The Committee is also responsible for the endorsement of these Guidelines and Expert Consensus Documents or statements.

The Task Force has classified and ranked the usefulness or efficacy of the recommended procedure and/or treatments and the Level of Evidence as indicated in the tables on page 3.

Diagnosis of chronic heart failure

Introduction

Methodology

These Guidelines are based on the Diagnostic and Therapeutic Guidelines published in 1995, 1997, and renewed in 2001,1–3 which has now been combined into one manuscript. Where new information is available, an update has been performed while other parts are unchanged or adjusted only to a limited extent.

The aim of this report is to provide updated practical guidelines for the diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of heart failure for use in clinical practice, as well as for epidemiological surveys and clinical trials. Particular attention in this update has been allocated to diastolic function and heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction (PLVEF). The intention has been to merge the previous Task Force report4 with the present update.

The Guidelines are intended as a support for practising physicians and other health care professionals concerned with the management of heart failure patients and to provide advice on how to manage these patients, including recommendations for referral. Documented and published evidence on diagnosis, efficacy, and safety is the main basis for these guidelines. ESC Guidelines are relevant to 49 member-states with diverse economies and therefore recommendations based on cost-effectiveness have been avoided in general. National health policy as well as clinical judgement may dictate the order of priority of implementation. It is recognized that some interventions may not be affordable in some countries for all appropriate patients. The recommendations in these guidelines should therefore always be considered in the light of national policies and local regulatory requirements for the administration of any diagnostic procedure, medicine, or device.

This report was drafted by a Writing Group of the Task Force (see title page) appointed by the CPG of the ESC. Within this Task Force, statements of Conflicts of Interests were collected, which are available at the ESC Office. The draft was sent to the Committee and the document reviewers (see title page) and after their input the document was updated, reviewed and then approved for presentation. The summary is based on a full document, which includes more background statements and includes references. This document is available at the ESC website www.escardio.org. The full report should be used when in doubt or when further information is required. An evidenced based approach to the evaluations has been applied including a grading of the evidence for recommendations. However, for the diagnosis, evidence is incomplete and in general based on consensus of expert opinions. Already in the 2001 version, it was decided not to use evidence grading in this part. The same approach has been used here.

Major conclusions or recommendations have been highlighted by Bullets.

Epidemiology

The ESC represents countries with a population of over 900 million, suggesting that there are at least 10 million patients with heart failure in those countries. There are also patients with myocardial systolic dysfunction without symptoms of heart failure and who constitute approximately a similar prevalence.5–7 The prognosis of heart failure is uniformly poor if the underlying problem cannot be rectified. Half of patients carrying a diagnosis of heart failure will die within 4 years, and in patients with severe heart failure >50% will die within 1 year.8,9 Many patients with heart failure have symptoms and PLVEF.10

Much is now known about the epidemiology of heart failure in Europe but the presentation and aetiology are heterogeneous and less is known about differences among countries.

Classes of recommendations

| Class I | Evidence and/or general agreement that a given diagnostic procedure/treatment is beneficial, useful, and effective |

| Class II | Conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of the treatment |

| Class IIa | Weight of evidence/opinion is in favour of usefulness/efficacy |

| Class IIb | Usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence/opinion |

| Class III* | Evidence or general agreement that the treatment is not useful/effective and in some cases may be harmful |

| Class I | Evidence and/or general agreement that a given diagnostic procedure/treatment is beneficial, useful, and effective |

| Class II | Conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of the treatment |

| Class IIa | Weight of evidence/opinion is in favour of usefulness/efficacy |

| Class IIb | Usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence/opinion |

| Class III* | Evidence or general agreement that the treatment is not useful/effective and in some cases may be harmful |

*Use of Class III is discouraged by the ESC.

Classes of recommendations

| Class I | Evidence and/or general agreement that a given diagnostic procedure/treatment is beneficial, useful, and effective |

| Class II | Conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of the treatment |

| Class IIa | Weight of evidence/opinion is in favour of usefulness/efficacy |

| Class IIb | Usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence/opinion |

| Class III* | Evidence or general agreement that the treatment is not useful/effective and in some cases may be harmful |

| Class I | Evidence and/or general agreement that a given diagnostic procedure/treatment is beneficial, useful, and effective |

| Class II | Conflicting evidence and/or a divergence of opinion about the usefulness/efficacy of the treatment |

| Class IIa | Weight of evidence/opinion is in favour of usefulness/efficacy |

| Class IIb | Usefulness/efficacy is less well established by evidence/opinion |

| Class III* | Evidence or general agreement that the treatment is not useful/effective and in some cases may be harmful |

*Use of Class III is discouraged by the ESC.

Levels of evidence

| Level of Evidence A | Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses |

| Level of Evidence B | Data derived from a single randomized clinical trial or large non-randomized studies |

| Level of Evidence C | Consensus of opinion of the experts and/or small studies, reprospective studies, registries |

| Level of Evidence A | Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses |

| Level of Evidence B | Data derived from a single randomized clinical trial or large non-randomized studies |

| Level of Evidence C | Consensus of opinion of the experts and/or small studies, reprospective studies, registries |

Levels of evidence

| Level of Evidence A | Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses |

| Level of Evidence B | Data derived from a single randomized clinical trial or large non-randomized studies |

| Level of Evidence C | Consensus of opinion of the experts and/or small studies, reprospective studies, registries |

| Level of Evidence A | Data derived from multiple randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses |

| Level of Evidence B | Data derived from a single randomized clinical trial or large non-randomized studies |

| Level of Evidence C | Consensus of opinion of the experts and/or small studies, reprospective studies, registries |

Studies show that the accuracy of diagnosis by clinical means alone is often inadequate,11,12 particularly in women, elderly, and obese. To study properly the epidemiology and prognosis and to optimize the treatment of heart failure, the uncertainty relating to the diagnosis must be minimized or avoided completely.

Descriptive terms in heart failure

Acute vs. chronic heart failure

The term acute heart failure (AHF) is often used exclusively to mean de novo AHF or decompensation of chronic heart failure (CHF) characterized by signs of pulmonary congestion, including pulmonary oedema. Other forms include hypertensive AHF, pulmonary oedema, cardiogenic shock, high output failure, and right heart failure. (See Guidelines on acute heart failure.13)

CHF often punctuated by acute exacerbations, is the most common form of heart failure. A definition of CHF is suceedingly given.

The present document will concentrate on the syndrome of CHF and leave out aspects on AHF.13 Thus, heart failure, if not stated otherwise, is referring to the chronic state.

Systolic vs. diastolic heart failure

Most heart failures are associated with evidence of left ventricular systolic dysfunction, although diastolic impairment at rest is a common if not universal accompaniment. In most cases, diastolic and systolic heart failures should not be considered as separate pathophysiological entities. Diastolic heart failure is often diagnosed when symptoms and signs of heart failure occur in the presence of a PLVEF (normal ejection fraction) at rest. Predominant diastolic dysfunction is relatively uncommon in younger patients but increases in importance in the elderly. PLVEF is more common in women, in whom systolic hypertension and myocardial hypertrophy with fibrosis are contributors to cardiac dysfunction.10,14

Other descriptive terms in heart failure

Right and left heart failure refer to syndromes presenting predominantly with congestion of the systemic or pulmonary veins. The terms do not necessarily indicate which ventricle is most severely damaged. High- and low-output, forward and backward, overt, treated, and congestive are other descriptive terms still in occasional use; the clinical utility of these terms is descriptive without etiological information and therefore of little use in determining modern treatment for heart failure.

Mild, moderate, or severe heart failure is used as a clinical symptomatic description, where mild is used for patients who can move around with no important limitations of dyspnea or fatigue, severe for patients who are markedly symptomatic and need frequent medical attention and moderate for the remaining patient cohort.

Definition of chronic heart failure

Many definitions of CHF exist15–18 but highlight only selective features of this complex syndrome. The diagnosis of heart failure relies on clinical judgement based on a history, physical examination, and appropriate investigations.

Heart failure should never be the only diagnosis.

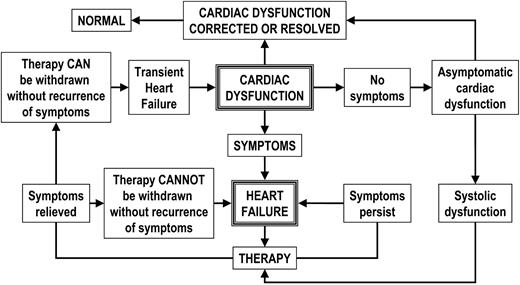

Heart failure is a syndrome in which the patients should have the following features: symptoms of heart failure, typically breathlessness or fatigue, either at rest or during exertion, or ankle swelling and objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction at rest (Table 1). The distinctions between cardiac dysfunction, persistent heart failure, heart failure that has been rendered asymptomatic by therapy, and transient heart failure are outlined in Figure 1. A clinical response to treatment directed at heart failure alone is not sufficient for diagnosis, although the patient should generally demonstrate some improvement in symptoms and/or signs in response to those treatments in which a relatively fast symptomatic improvement could be anticipated (e.g. diuretic or nitrate administration).

Asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction is considered as precursor of symptomatic CHF and is associated with high mortality.19 It is important when diagnosed and treatment is available, and the condition is therefore included in these Guidelines.

Aspects of the pathophysiology of the symptoms of heart failure relevant to diagnosis

The origin of the symptoms of heart failure is not fully understood. Increased pulmonary capillary pressure is undoubtedly responsible for pulmonary oedema in part, but studies conducted during exercise in patients with CHF demonstrate only a weak relationship between capillary pressure and exercise performance.20,21 This suggests either that raised pulmonary capillary pressure is not the only factor responsible for exertional breathlessness (e.g. lungwater and plasma albumin) or that current techniques to measure true pulmonary capillary pressure may not be adequate. Variation in the degree of mitral regurgitation will also influence breathlessness.

Possible methods for the diagnosis of heart failure in clinical practice

Symptoms and signs in the diagnosis of heart failure

Breathlessness, ankle swelling, and fatigue are the characteristic symptoms and signs of heart failure but may be difficult to interpret, particularly in elderly patients, in obese, and in women. It should be interpreted carefully and different modes (e.g. effort and nocturnal) should be assessed.

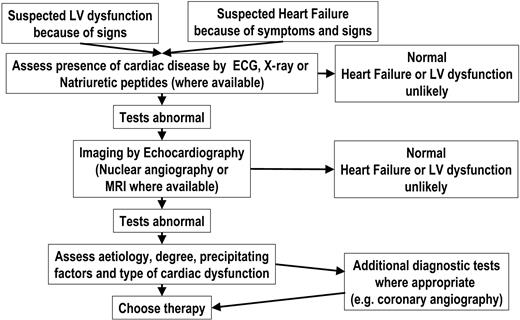

Symptoms and signs are important as they alert the observer to the possibility that heart failure exists. The clinical suspicion of heart failure must be confirmed by more objective tests particularly aimed at assessing cardiac function (Figure 2).

Fatigue is also an essential symptom in heart failure. The origins of fatigue are complex including low cardiac output, peripheral hypoperfusion, skeletal muscle deconditioning, and confounded by difficulties in quantifying this symptom.

Peripheral oedema, raised venous pressure, and hepatomegaly are the characteristic signs of congestion of systemic veins.22,23 Clinical signs of heart failure should be assessed in a careful clinical examination, including observing, palpating, and auscultating the patient.

Symptoms and the severity of heart failure

Once a diagnosis of heart failure has been established, symptoms may be used to classify the severity of heart failure and should be used to monitor the effects of therapy. However, as noted subsequently, symptoms cannot guide the optimal titration of neurohormonal blockers. The New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification is in widespread use (Table 2). In other situations, the classification of symptoms into mild, moderate, or severe is used. Patients in NYHA class I would have to have objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction, have a past history of heart failure symptoms and be receiving treatment for heart failure in order to fulfil the basic definition of heart failure.

There is a poor relationship between symptoms and the severity of cardiac dysfunction.10,24 However, symptoms may be related to prognosis particularly if persisting after therapy.25

In acute myocardial infarction, the classification described by Killip26 has been used to describe symptoms and signs.27 It is important to recognize the common dissociation between symptoms and cardiac dysfunction. Symptoms are also similar in patients across different levels of ejection fraction.28 Mild symptoms should not be equated with minor cardiac dysfunction.

Electrocardiogram

Electrocardiographic changes are common in patients suspected of having heart failure whether or not the diagnosis proves to be correct. An abnormal ECG, therefore, has little predictive value for the presence of heart failure. On the other hand, if the ECG is completely normal, heart failure, especially due LV systolic dysfunction, is unlikely. The presence of pathological Q-waves may suggest myocardial infarction as the cause of cardiac dysfunction. A QRS width >120 ms suggests that cardiac dyssynchrony may be present and a target for treatment.

A normal electrocardiogram (ECG) suggests that the diagnosis of CHF should be carefully reviewed.

The chest X-ray

Chest X-ray should be part of the initial diagnostic work-up in heart failure. It is useful to detect cardiomegaly and pulmonary congestion; however, it has only predictive value in the context of typical signs and symptoms and in abnormal ECG.

Haematology and biochemistry

Routine diagnostic evaluation of patients with CHF includes: complete blood count (Hb, leukocytes, and platelets), S-electrolytes, S-creatinine, S-glucose, S-hepatic enzymes, and urinalysis. Additional tests to evaluate thyroid function should be considered according to clinical findings. In acute exacerbations, acute myocardial infarction is excluded by myocardial specific enzyme analysis.

Natriuretic peptides

As the diagnostic potential of natriuretic peptides is less clear cut when systolic function is normal, there is increasing evidence that their elevation can indicate diastolic dysfunction is present.29,30 Other common cardiac abnormalities that may cause elevated natriuretic peptide levels include left ventricular hypertrophy, valvular heart disease, acute or chronic ischaemia or hypertension,31 and pulmonary embolism.32

Plasma concentrations of certain natriuretic peptides or their precursors, especially BNP and NT-proBNP, are helpful in the diagnosis of heart failure.

A low-normal concentration in an untreated patient makes heart failure unlikely as the cause of symptoms.

BNP and NT-proBNP have considerable prognostic potential, although evaluation of their role in treatment monitoring remains to be determined.

In considering the use of BNP and NT-proBNP as diagnostic aids, it should be emphasized that a ‘normal’ value cannot completely exclude cardiac disease, but a normal or low concentration in an untreated patient makes heart failure unlikely as the cause of symptoms.

In clinical practice today, the place of BNP and NT-proBNP is as ‘rule out’ tests to exclude significant cardiac disease. Particularly in primary care but also in certain aspects of secondary care (e.g. the emergency room and clinics.) The cost-effectiveness of the test suggest that a normal result should obviate the need for further cardiological tests such as in the first instance echocardiography as well as more expensive investigations.33

Echocardiography

The access to and use of echocardiography is encouraged for the diagnosis of heart failure. Transthoracic Doppler echocardiography (TDE) is rapid, safe, and widely available.

Echocardiography is the preferred method for the documentation of cardiac dysfunction at rest.

The most important measurement of ventricular function is the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) for distinguishing patients with cardiac systolic dysfunction from patients with preserved systolic function.

Assessment of LV diastolic function

Assessment of diastolic function may be clinically useful: (1) to detect abnormalities of diastolic function in patients who present with CHF and normal left ventricular ejection fraction, (2) in determining prognosis in heart failure patients, (3) in providing a non-invasive estimate of left ventricular diastolic pressure, and (4) in diagnosing constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy.

Diagnostic criteria of diastolic dysfunction

A diagnosis of primary diastolic heart failure requires three conditions to be simultaneously satisfied: (1) presence of signs or symptoms of CHF, (2) presence of normal or only mildly abnormal left ventricular systolic function (LVEF≥45–50%), and (3) evidence of abnormal left ventricular relaxation, diastolic distensibility, or diastolic stiffness.34 Furthermore, it is essential to exclude pulmonary disease.35

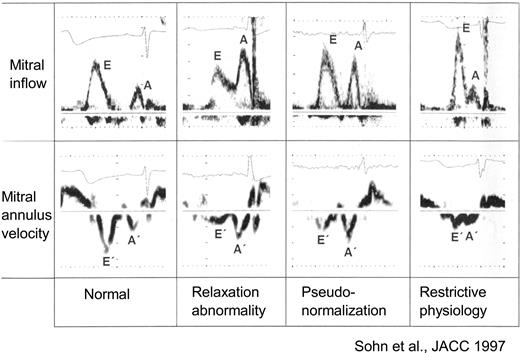

At an early stage of diastolic dysfunction, there is typically a pattern of ‘impaired myocardial relaxation’ with a decrease in peak transmitral E-velocity, a compensatory increase in the atrial-induced (A) velocity and therefore a decrease in the E/A ratio.

In patients with advanced cardiac disease, there may be a pattern of ‘restrictive filling’, with an elevated peak E-velocity, a short E-deceleration time, and a markedly increased E/A ratio. The elevated peak E-velocity is due to elevated left atrial pressure that causes an increase in the early-diastolic transmitral pressure gradient.36

In patients with an intermediate pattern between impaired relaxation and restrictive filling the E/A ratio and the deceleration time may be normal, a so-called ‘pseudonormalized filling pattern’. This pattern may be distinguished from normal filling by the demonstration of reduced peak E′-velocity by TDI.37

The three filling patterns ‘impaired relaxation’, ‘pseudonormalized filling’, and ‘restrictive filling’ represent mild, moderate, and severe diastolic dysfunction, respectively37 (Figure 3). Thus, by using the combined assessment of transmitral blood flow velocities and mitral annular velocities, it becomes possible to perform staging of diastolic dysfunction during a routine echocardiographic examination. We still lack prospective outcome studies that investigate if assessment of diastolic function by these criteria may improve management of heart failure patients.

Transoesophageal echocardiography is not recommended routinely and can only be advocated in patients who have an inadequate echo window, in complicated valvular patients, and in patients with suspected dysfunction of mechanical mitral valve prosthesis or when it is mandatory to identify or exclude a thrombus in the atrial appendage.

Repeated echocardiography can be recommended in the follow-up of patients with heart failure only when there is an important change in the clinical status suggesting significant improvement or deterioration in cardiac function.

Additional non-invasive tests to be considered

In patients in whom echocardiography at rest has not provided enough information and in patients with coronary artery disease (e.g. severe or refractory CHF and coronary artery disease), further non-invasive imaging may include stress echocardiography, radio-nuclide imaging, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR).

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR)

CMR is a versatile, highly accurate, and reproducible imaging technique for the assessment of left and right ventricular volumes, global function, regional wall motion, myocardial thickness, thickening, myocardial mass, and cardiac valves.38,39 The method is well suited for detection of congenital defects, masses and tumours, valvular, and pericardial disease.

Pulmonary function

Measurements of lung function are of little value in diagnosing CHF. However, they are useful in excluding respiratory causes of breathlessness. Spirometry can be useful to evaluate the extent of obstructive airways disease which is a common comorbidity in patients with heart failure.

Exercise testing

In clinical practice, exercise testing is of limited value for the diagnosis of heart failure. However, a normal maximal exercise test in a patient not receiving treatment for heart failure excludes heart failure as a diagnosis. The main applications of exercise testing in CHF are focused more on functional and treatment assessment and on prognostic stratification.

Invasive investigation

Invasive investigation is generally not required to establish the presence of CHF but may be important in elucidating the cause or to obtain prognostic information.

Cardiac catheterization

Coronary angiography should be considered in patients with acute or acutely decompensated CHF and in patients with severe heart failure (shock or acute pulmonary oedema) who are not responding to initial treatment. Coronary angiography should also be considered in patients with angina pectoris or any other evidence of myocardial ischaemia if they are not responding to appropriate anti-ischaemic treatment. Revascularization has not been shown to alter prognosis in heart failure in clinical trials and therefore, in the absence of angina pectoris unresponsive to medical therapy, coronary arteriography is not indicated. Coronary angiography is also indicated in patients with refractory heart failure of unknown aetiology and in patients with evidence of severe mitral regurgitation or aortic valve disease.

Monitoring of haemodynamic variables by means of a pulmonary arterial catheter is indicated in patients who are hospitalized for cardiogenic shock or to direct treatment of patients with CHF not responding promptly to initial and appropriate treatment. Routine right heart catheterization should not be used to tailor chronic therapy.

Tests of neuroendocrine evaluations other than natriuretic peptides

Tests of neuroendocrine activation are not recommended for diagnostic or prognostic purposes in individual patients.

Holter electrocardiography: ambulatory ECG and long-time ECG recording (LTER)

Conventional Holter monitoring is of no value in the diagnosis of CHF, though it may detect and quantify the nature, frequency and duration of atrial and ventricular arrhythmias which could be causing or exacerbating symptoms of heart failure. Recording LTER should be restricted to patients with CHF and symptoms suggestive of an arrhythmia.

Requirements for the diagnosis of heart failure in clinical practice

The echocardiogram is the single most effective tool in widespread clinical use. Other conditions may mimic or exacerbate the symptoms and signs of heart failure and therefore need to be excluded (Table 3). An approach (Figure 2) to the diagnosis of heart failure in symptomatic patients should be performed routinely in patients with suspected heart failure in order to establish the diagnosis. Additional tests (Table 4) should be performed or re-evaluated in cases in which diagnostic doubt persists or clinical features suggest a reversible cause for heart failure.

To satisfy the definition of heart failure, symptoms of heart failure and objective evidence of cardiac dysfunction must be present (Table 1). The assessment of cardiac function by clinical criteria alone is unsatisfactory. Cardiac dysfunction should be assessed objectively.

Figure 2 represents a simplified plan for the evaluation of a patient presenting with symptoms suggestive of heart failure or signs giving suspicion of left ventricular systolic dysfunction. Table 5 provides a management outline connecting the diagnosis component of the guidelines with the treatment section.

Prognostication

The problem of defining prognosis in heart failure is complex for many reasons: several aetiologies, frequent comorbidities, limited ability to explore the paracrine pathophysiological systems, varying individual progression and outcome (sudden vs. progressive heart failure death), and efficacy of treatments. Moreover, several methodological limitations weaken many prognostic studies. The variables more consistently indicated as independent outcome predictors are reported in Table 6.

Treatment of heart failure

Aims of treatment in heart failure

Prevention—a primary objective

Prevention and/or controlling of diseases leading to cardiac dysfunction and heart failure.

Prevention of progression to heart failure once cardiac dysfunction is established.

Maintenance or improvement in quality of life

Improved survival

Prevention of heart failure

When myocardial dysfunction is already present, the first objective is to remove the underlying cause of ventricular dysfunction if possible (e.g. ischaemia, toxic substances, alcohol, drugs, and thyroid disease), providing the benefits of intervention outweigh the risks. When the underlying cause cannot be corrected treatment should be directed at delaying or preventing left ventricular dysfunction that will increase the risk of sudden death and the development of heart failure.

The development of ventricular dysfunction and heart failure may be delayed or prevented by treatment of conditions leading to heart failure, in particular in patients with hypertension and/or coronary artery disease (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).40

The prevention of heart failure should always be a primary objective.

How to modulate progression from asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction to heart failure is described on page 1133, Treatment of Asymptomatic Left Ventricular Dysfunction.

Management of chronic heart failure

The therapeutic approach in patients with CHF that is caused by left ventricular systolic dysfunction includes general advice and other non-pharmacological measures, pharmacological therapy, mechanical devices, and surgery. The currently available types of management are outlined in Tables 5 and 7.

Non-pharmacological management

General advice and measures

(Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C for non-pharmacological management unless stated otherwise)

Educating patients and family

Patients with CHF and their close relatives should receive general advice.

Weight monitoring

Patients are advised to weigh on a regular basis to monitor weight gain (preferably as part of a regular daily routine, for instance after morning toilet) and, in case of a sudden unexpected weight gain of >2 kg in 3 days, to alert a health care provider or adjust their diuretic dose accordingly (e.g. to increase the dose if a sustained increase in weight is noted).

Dietary measures

Sodium

Controlling the amount of salt in the diet is a problem, that is, more important in advanced than in mild heart failure.

Fluids

Instructions on fluid control should be given to patients with advanced heart failure, with or without hyponatraemia. The exact amount of fluid restriction remains unclear, however. In practice, a fluid restriction of 1.5–2 L/day is advised in advanced heart failure.

Alcohol

Moderate alcohol intake (one beer, 1–2 glasses of wine/day) is permitted other than in case of alcoholic cardiomyopathy when it is prohibited.

Obesity

Treatment of CHF should include weight reduction in obese patients.

Abnormal weight loss

Clinical or subclinical malnutrition is present in ∼50% of patients with severe CHF. The wasting of total body fat and lean body mass that accompanies weight loss is called cardiac cachexia. Cardiac cachexia is an important predictor of reduced survival.41

Smoking

Smoking should always be discouraged. The use of smoking cessation aids should be actively encouraged and may include nicotine replacement therapies.

Travelling

High altitudes or very hot or humid places should be discouraged. In general, short air flights are preferable to long journeys by other means of transport.

Sexual activity

It is not possible to dictate guidelines about sexual activity counselling. Recommendations are given to reassure the not severely compromised, but frightened patient, to reassure the partner who is often even more frightened, and perhaps refer the couple for specialist counselling. Little is known about the effects of treatments for heart failure on sexual function.

Advice on immunizations

There is no documented evidence of the effects of immunization in patients with heart failure. Immunization for influenza is widely used.

Drug counselling

Self-management (when practical) of the dose of the diuretic, based on changes in symptoms and weight (fluid balance), should be encouraged. Within pre-specified and individualized limits, patients are able to adjust their diuretics.

Drugs to avoid or beware

The following drugs should be used with caution when co-prescribed with any form of heart failure treatment or avoided:

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) and coxibs

Class I anti-arrhythmic agents (page 1131)

Calcium antagonists (verapamil, diltiazem, and short-acting dihydropyridine derivatives (page 1126)

Tricyclic anti-depressants

Corticosteroids

Lithium

Rest, exercise, and exercise training

Rest

In acute heart failure or destabilization of CHF, physical rest or bed rest is recommended.

Exercise

Exercise improves skeletal muscle function and therefore overall functional capacity. Patients should be encouraged and advised on how to carry out daily physical and leisure time activities that do not induce symptoms. Exercise training programs are encouraged in stable patients in NYHA class II–III. Standardized recommendations for exercise training in heart failure patients by the European Society of Cardiology have been published.42

Pharmacological therapy

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors

Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors are recommended as first-line therapy in patients with a reduced left ventricular systolic function expressed as a subnormal ejection fraction, i.e. <40–45% with or without symptoms (see non-invasive imaging; page 1121 Diagnosis section) (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).

ACE-inhibitors should be uptitrated to the dosages shown to be effective in the large, controlled trials in heart failure (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A), and not titrated based on symptomatic improvement alone (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C).

ACE-inhibitors in asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction

Asymptomatic patients with a documented left ventricular systolic dysfunction should be treated with an ACE-inhibitor to delay or prevent the development of heart failure. ACE-inhibitors also reduce the risk of myocardial infarction and sudden death in this setting (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).43–46

ACE-inhibitors in symptomatic heart failure

Target maintenance dose ranges of ACE-inhibitors shown to be effective in various trials are given in Table 8. Recommended initiating and maintenance dosages of ACE-inhibitors which have been approved for the treatment of heart failure in Europe are presented in Table 9.

All patients with symptomatic heart failure that is caused by systolic left ventricular dysfunction should receive an ACE-inhibitor (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).47

ACE-inhibition improves survival, symptoms, functional capacity, and reduces hospitalization in patients with moderate and severe heart failure and left ventricular systolic dysfunction.

ACE-inhibitors should be given as the initial therapy in the absence of fluid retention. In patients with fluid retention, ACE-inhibitors should be given together with diuretics (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).47,48

ACE inhibition should be initiated in patients with signs or symptoms of heart failure, even if transient, after the acute phase of myocardial infarction, even if the symptoms are transient to improve survival and to reduce reinfarctions and hospitalizations for heart failure (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).44,45,49

Asymptomatic patients with a documented left ventricular systolic dysfunction benefit from long-term ACE-inhibitor therapy (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).43–46

Important adverse effects associated with ACE-inhibitors are cough, hypotension, renal insufficiency, hyperkalaemia, syncope, and angioedema. Angiotensin receptor blockers may be used as an effective alternative in patients who develop cough or angioedema on an ACE-inhibitor (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A). Changes in systolic and diastolic blood pressure and increases in serum creatinine are usually small in normotensive patients.

ACE-inhibitor treatment is contra-indicated in the presence of bilateral renal artery stenosis and angioedema during previous ACE-inhibitor therapy (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence A).

The dose of ACE-inhibitors should always be initiated at the lower dose level and titrated to the target dose. The recommended procedures for starting an ACE-inhibitor are given in Table 10.

Regular monitoring of renal function is recommended: (1) before, 1–2 weeks after each dose increment, and at 3–6 months interval; (2) when the dose of an ACE-inhibitor is increased or other treatments, which may affect renal function, are added (e.g. aldosterone antagonist or angiotensin receptor blocker), (3) in patients with past or present renal dysfunction or electrolyte disturbances more frequent measurements should be made, or (4) during any hospitalization.

Diuretics

Loop diuretics, thiazides, and metolazone

Detailed recommendations and major side effects are outlined in Tables 11 and 12.

Diuretics are essential for symptomatic treatment when fluid overload is present and manifest as pulmonary congestion or peripheral oedema. The use of diuretics results in rapid improvement of dyspnoea and increased exercise tolerance (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).50,51

There are no controlled randomized trials that have assessed the effect on symptoms or survival of these agents. Diuretics should always be administered in combination with ACE-inhibitors and beta-blockers if tolerated (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C).

Potassium-sparing diuretics

Potassium-sparing diuretics should only be prescribed if hypokalaemia persists despite ACE inhibition, or in severe heart failure despite the combination ACE inhibition and low-dose spironolactone (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C). In patients who are unable to tolerate even low doses of aldosterone antagonists due to hyperkalaemia and renal dysfunction, amiloride or triamterene may be used (Class of recommendation IIb, level of evidence C).

Potassium supplements are generally ineffective in this situation (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence C).

The use of all potassium-sparing diuretics should be monitored by repeated measurements of serum creatinine and potassium. A practical approach is to measure serum creatinine and potassium every 5–7 days after initiation of treatment until the values are stable. Thereafter, measurements can be made every 3–6 months.

Beta-adrenoceptor antagonists

Beta-blockers should be considered for the treatment of all patients (in NYHA class II–IV) with stable, mild, moderate, and severe heart failure from ischaemic or non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies and reduced LVEF on standard treatment, including diuretics, and ACE-inhibitors, unless there is a contraindication (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).52–58

Beta-blocking therapy reduces hospitalizations (all, cardiovascular, and heart failure), improves the functional class and leads to less worsening of heart failure. This beneficial effect has been consistently observed in subgroups of different age, gender, functional class, LVEF, and ischaemic or non-ischaemic aetiology (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).

In patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, with or without symptomatic heart failure, following an acute myocardial infarction long-term beta-blockade is recommended in addition to ACE inhibition to reduce mortality (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).59

Differences in clinical effects may be present between different beta-blockers in patients with heart failure.60,61 Accordingly, only bisoprolol, carvedilol, metoprolol succinate and nebivolol can be recommended (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).

Initiation of therapy

The initial dose should be small and increased slowly and progressively to the target dose used in the large clinical trials. Up-titration should be adapted to individual responses.

During titration, beta-blockers may reduce heart rate excessively, temporarily induce myocardial depression, and exacerbate symptoms of heart failure. Table 13 gives the recommended procedure for the use of beta-blockers in clinical practice and contraindications.

Table 14 shows the titration scheme of the drugs used in the most relevant studies.

Aldosterone receptor antagonists

Administration and dosing considerations for aldosterone antagonists are provided in Table 15.

Aldosterone antagonists are recommended in addition to ACE-inhibitors, beta-blockers and diuretics in advanced heart failure (NYHA III–IV) with systolic dysfunction to improve survival and morbidity (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).62

Aldosterone antagonists are recommended in addition to ACE-inhibitors and beta-blockers in heart failure after myocardial infarction with left ventricular systolic dysfunction and signs of heart failure or diabetes to reduce mortality and morbidity (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).63

Angiotensin II receptor blockers

For patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction:In NYHA class III patients remaining symptomatic despite therapy with diuretics, ACE-inhibitors, and beta-blockers, there is no definite evidence for the recommendation of next addition; an ARB or an aldosterone antagonist to reduce further heart failure hospitalizations or mortality.

Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) can be used as an alternative to ACE inhibition in symptomatic patients intolerant to ACE-inhibitors to improve morbidity and mortality (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).64–67

ARBs and ACE-inhibitors seem to have similar efficacy in CHF on mortality and morbidity (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B). In acute myocardial infarction with signs of heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction ARBs and ACE-inhibitors have similar or equivalent effects on mortality (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).68

ARBs can be considered in combination with ACE-inhibitors in patients who remain symptomatic, to reduce mortality (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B) and hospital admissions for heart failure (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).65,69–71,170

Concerns raised by initial studies about a potential negative interaction between ARBs and beta-blockers have not been confirmed by recent studies in post-myocardial infarction or CHF (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).65,68

Dosing

Initiation and monitoring of ARBs, which are outlined in Table 10, are similar to procedures for ACE-inhibitors. Available ARBs and the recommended dose levels are shown in Table 16.

Cardiac glycosides

Cardiac glycosides are indicated in atrial fibrillation and any degree of symptomatic heart failure, whether or not left ventricular dysfunction is the cause. Cardiac glycosides slow the ventricular rate, which improves ventricular function and symptoms (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).72

A combination of digoxin and beta-blockade appears superior to either agent alone in patients with atrial fibrillation (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B).73

Digoxin has no effect on mortality but may reduce hospitalizations and, particularly, worsening heart failure hospitalizations, in the patients with heart failure caused by left ventricular systolic dysfunction and sinus rhythm treated with ACE-inhibitors, beta-blockers, diuretics and in severe heart failure, spironolactone (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence A).

Contraindications to the use of cardiac glycosides include bradycardia, second- and third-degree AV block, sick sinus syndrome, carotid sinus syndrome, Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy, hypokalaemia, and hyperkalaemia.

Digoxin

The usual daily dose of oral digoxin is 0.125–0.25 mg if serum creatinine is in the normal range (in the elderly 0.0625–0.125 mg, occasionally 0.25 mg).

Vasodilator agents in chronic heart failure

There is no specific role for direct-acting vasodilator agents in the treatment of CHF (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence A) though they may be used as adjunctive therapy for angina or concomitant hypertension (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).

Hydralazine-isosorbide dinitrate

In case of intolerance for ACE-inhibitors and ARBs, the combination hydralazine/nitrates can be tried to reduce mortality and morbidity and improved quality of life (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B).74

Nitrates

Nitrates may be used for the treatment of concomitant angina or relief of dyspnoea. (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C). Evidence that oral nitrates improve symptoms of heart failure chronically or during an acute exacerbation is lacking.

Alpha-adrenergic blocking drugs

There is no evidence to support the use of alpha-adrenergic blocking drugs in heart failure (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence B).75

Calcium antagonists

As long-term safety data with felodipine and amlodipine indicate a neutral effect on survival, they may offer a safe alternative for the treatment of concomitant arterial hypertension or angina not controlled by nitrates and beta-blockers.

Calcium antagonists are not recommended for the treatment of heart failure caused by systolic dysfunction. Diltiazem- and verapamil-type calcium antagonists, in particular, are not recommended in heart failure because of systolic dysfunction; they are contraindicated in addition to beta-blockade (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence C).76,77

Addition of newer calcium antagonists (felodipine and amlodipine) to standard treatment for heart failure does not improve symptoms and does not impact on survival (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence A).76,77

Nesiritide

Nesiritide, a recombinant human brain or B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), has been shown to be efficacious in improving subjective dyspnoea score as well as inducing significant vasodilation when administered intravenous to patients with acute heart failure. Clinical experience with nesiritide is still limited. Nesiritide may cause hypotension and some patients are non-responders.

Positive inotropic therapy

Repeated or prolonged treatment with oral inotropic agents increases mortality and is not recommended in CHF (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence A).

Intravenous administration of inotropic agents is commonly used in patients with severe heart failure with signs of both pulmonary congestion and peripheral hypoperfusion. However, treatment-related complications may occur and their effect on prognosis is uncertain. Depending on agent level of evidence and strength of recommendation varies.13

Preliminary data suggests that some calcium sensitizers (e.g. levosimendan) may have beneficial effects on symptoms and end-organ function and are safe.78

Anti-thrombotic agents

Patients with CHF are at high risk of thromboembolic events. Factors predisposing to thromboembolism are low cardiac output with relative stasis of blood in dilated cardiac chambers, poor contractility, regional wall motion abnormalities, and atrial fibrillation. There is little evidence to support the concomitant treatment with an ACE-inhibitor and aspirin in heart failure.81–83

In CHF associated with atrial fibrillation, a previous thromboembolic event or a mobile left ventricular thrombus, anti-coagulation is firmly indicated (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).79

There is little evidence to show that anti-thrombotic therapy modifies the risk of death or vascular events in patients with heart failure.

After a prior myocardial infarction, either aspirin or oral anti-coagulants are recommended as secondary prophylaxis (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C).80

Aspirin should be avoided in patients with recurrent hospitalization with worsening heart failure (Class of recommendation IIb, level of evidence B). Because of the potential for increased bleeding complications, anti-coagulant therapy should be administered under the most controlled conditions, planning monitoring in properly managed anti-coagulation clinics.

In general, the rates of thromboembolic complications in heart failure are sufficiently low to limit the evaluation of any potential beneficial effect of anti-coagulation/anti-thrombotic therapy in these patients.

Anti-arrhythmics

Anti-arrhythmic drugs other than beta-blockers are generally not indicated in patients with CHF. In patients with atrial fibrillation (rarely flutter), non-sustained, or sustained ventricular tachycardia treatment with anti-arrhythmic agents may be indicated.

Class I anti-arrhythmics

Class I anti-arrhythmics should be avoided as they may provoke fatal ventricular arrhythmias, have an adverse haemodynamic effect and reduce survival in heart failure (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence B).84

Class II anti-arrhythmics

Beta-blockers reduce sudden death in heart failure (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A) (see also page 1127).85 Beta-blockers may also be indicated alone or in combination with amiodarone or non-pharmacological therapy in the management of sustained or non-sustained ventricular tachy-arrhythmias (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C).86

Class III anti-arrhythmics

Routine administration of amiodarone in patients with heart failure is not justified (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence A).89,90

Amiodarone is effective against most supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A). It may restore and maintain sinus rhythm in patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation even in the presence of enlarged left atria, or improve the success of electrical cardioversion and amiodarone is the preferred treatment in this condition.87,88 Amiodarone is the only anti-arrhythmic drug without clinically relevant negative inotropic effects.

Oxygen therapy

Oxygen is used for the treatment of AHF, but in general has no application in CHF (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence C).

Surgery and devices

Revascularization procedures, mitral valve surgery, and ventricular restoration

If clinical symptoms of heart failure are present, surgically correctable pathologies must always be considered (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C).

Revascularization

There are no data from multicenter trials to support the use of revascularization procedures for the relief of heart failure symptoms. Single centre, observational studies on heart failure of ischaemic origin, suggest that revascularization might lead to symptomatic improvement (Class of recommendation IIb, level of evidence C).

Until the results of randomized trials are reported, revascularization (surgical or percutaneous) is not recommended as routine management of patients with heart failure and coronary disease (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence C).

Mitral valve surgery

Mitral valve surgery in patients with severe left ventricular systolic dysfunction and severe mitral valve insufficiency due to ventricular insuffiency may lead to symptomatic improvement in selected heart failure patients (Class of recommendation IIb, level of evidence C). This is also true for secondary mitral insufficiency due to left ventricular dilatation.

Left ventricular restoration

LV aneurysmectomy

LV aneurysmectomy is indicated in patients with large, discrete left ventricular aneurysms who develop heart failure (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C).

Cardiomyoplasty

Currently, cardiomyoplasty cannot be recommended for the treatment of heart failure (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence C).

Cardiomyoplasty cannot be considered a viable alternative to heart transplantation (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence C).

Partial left ventriculectomy (Batista operation)

Partial left ventriculectomy cannot be recommended for the treatment of heart failure (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C). Furthermore, the Batista operation should not be considered an alternative to heart transplantation (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence C).

External ventricular restoration

Currently, external ventricular restoration cannot be recommended for the treatment of heart failure. Preliminary data suggest an improvement in LV dimensions and NYHA class with some devices (Class of recommendation IIb, level of evidence C).

Pacemakers

Bi-ventricular pacing improves symptoms, exercise capacity, and reduces hospitalizations.91–94 A beneficial effect on the composite of long-term mortality or all-cause hospitalization has recently been demonstrated, as well as a significant effect on mortality.171

Pacemakers have been used in patients with heart failure to treat bradycardia when conventional indications exist. Pacing only of the right ventricle in patients with systolic dysfunction will induce ventricular dyssynchrony and may increase symptoms (Class of recommendation III, level of evidence A).

Resynchronization therapy using bi-ventricular pacing can be considered in patients with reduced ejection fraction and ventricular dyssynchrony (QRS width ≥120 ms) and who remain symptomatic (NYHA III–IV) despite optimal medical therapy to improve symptoms (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A), hospitalizations (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A) and mortality (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence B).

Implantable cardioverter defibrillators

In patients with documented sustained ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation, the ICD is highly effective in treating recurrences of these arrhythmias, either by anti-tachycardia pacing or cardioversion/defibrillation, thereby reducing morbidity and the need for rehospitalization. The selection criteria, the limited follow-up and increased morbidity associated with ICD-implantation and the low cost-effectiveness make it inappropariate to extend the findings into a general population with CHF. The COMPANION trial included patients with left ventricular systolic dysfunction, wide QRS complex suggesting dyssynchrony and heart failure and showed that implantation of an ICD in combination with resynchronization in patients with severe heart failure reduced mortality and morbidity (See under Resynchronization).93 However, CRT-D was not superior to CRT alone in terms of reducing mortality and therefore the treatment associated with lower morbidity and cost may be preferred for the majority of patients. CRT-D should be reserved for patients considered at very high risk of sudden death despite medical treatment and CRT alone. The cost-effectiveness of this treatment needs to be established.98 In the SCD-HeFT trial, 2521 patients with CHF and LVEF≤35% were randomized to placebo, amiodarone, or single-lead ICD implantation. After a median follow-up of 45.5 months, there was a significant reduction in mortality by ICD therapy; HR 0.77 (97.5% CI: 0.62–0.96; P=0.007).90 There was no difference between placebo and amiodarone on survival.

Implantation of an implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICD) in combination with bi-ventricular pacing can be considered in patients who remain symptomatic with severe heart failure NYHA class III–IV with LVEF≤35% and QRS duration≥120 ms to improve mortality or morbidity (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B).93

ICD therapy is recommended to improve survival in patients who have survived cardiac arrest or who have sustained ventricular tachycardia, which is either poorly tolerated or associated with reduced systolic left ventricular function (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).95

ICD implantation is reasonable in selected patients with LVEF<30–35%, not within 40 days of a myocardial infarction, on optimal background therapy including ACE-inhibitor, ARB, beta-blocker, and an aldosterone antagonist, where appropriate, to reduce sudden death (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).90,96,97

Several recent meta-analyses estimated the effect of ICD implantation on all-cause mortality in symptomatic patients with reduced ejection fraction.83,99,100 As the effectiveness with ICD is time-dependent,101 anticipated duration of treatment is important to establish cost-effectiveness. Accordingly, the age of the patient and non-cardiac comorbidity must also be taken into account. Treatment of patients in NYHA class IV is not well established unless associated with CRT in the context of dyssynchrony. There is no evidence that patients with DCM obtain proportionally less benefit but as the prognosis of this group is generally better, the absolute benefits may be less.83

Heart replacement therapies: heart transplantation, ventricular assist devices, and artificial heart

Heart transplantation

Patients who should be considered for heart transplantation are those with severe symptoms of heart failure with no alternative form of treatment and with a poor prognosis. The introduction of new treatments has probably modified the prognostic significance of the variables traditionally used to identify heart transplant candidates i.e. VO2 max (see prognostication page 1122). The patient must be willing and capable to undergo intensive medical treatment, and be emotionally stable so as to withstand the many uncertainties likely to occur both before and after transplantation. The contraindications for heart transplantation are shown in Table 17.

Heart transplantation is an accepted mode of treatment for end stage heart failure. Although controlled trials have never been conducted, it is considered to significantly increase survival, exercise capacity, return to work and quality of life compared with conventional treatment, provided proper selection criteria are applied (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C).

Besides shortage of donor hearts, the main problem of heart transplantation is rejection of the allograft, which is responsible for a considerable percentage of deaths in the first postoperative year. The long-term outcome is limited predominantly by the consequences of immuno-suppression (infection, hypertension, renal failure, malignancy, and by transplant coronary vascular disease).102

Ventricular assist devices and artificial heart

Current indications for left ventricular assist devices and artificial heart include bridging to transplantation, acute severe myocarditis, and in some patients permanent haemodynamic support (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C).

Left ventricular assist devices are being implanted as a bridge to transplantation. Experience from long-term treatment is accumulating but these devices are not recommended for routine long-term use (Class of recommendation IIb, level of evidence B).103

Ultrafiltration

Ultrafiltration may be used to treat fluid overload (pulmonary or peripheral oedema) refractory to diuretics.104 However, in most patients with severe heart failure, the relief is temporary.105

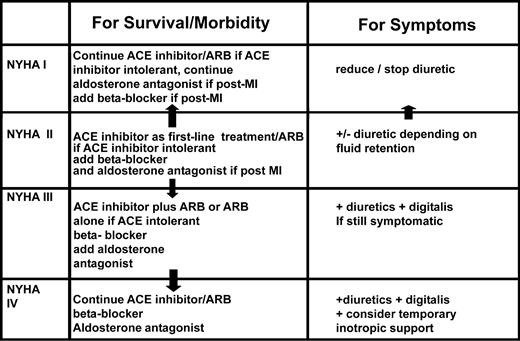

Choice and timing of pharmacological therapy

The choice of pharmacological therapy in the various stages of heart failure that is caused by systolic dysfunction is displayed in Table 18. Before initiating therapy, the correct diagnosis needs to be established and considerations should be given to the Management Outline presented in Table 5.

Asymptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction

In general, the lower the ejection fraction, the higher the risk of developing heart failure or sudden death. Treatment with an ACE-inhibitor is recommended in patients with reduced LVEF if indicated by a substantial reduction in LVEF (see section on echocardiography in the Diagnosis section) (recommendation page 1120).

Beta-blockers should be added to the therapy in patients with asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction, especially if following an acute myocardial infarction (recommendation page 1127).

Symptomatic left ventricular systolic dysfunction: heart failure NYHA class II (Figure 4)

Without signs of fluid retention

ACE-inhibitor (recommendation page 1126). Titrate to the target dose used in large controlled trials (Table 8). Add a beta-blocker (recommendation page 1127) and titrate to target dosages used in large controlled trials (Table 14).

With signs of fluid retention

Diuretics in combination with an ACE-inhibitor followed by a beta-blocker. First, the ACE-inhibitor and diuretic should be co-administered. When symptomatic improvement occurs (i.e. fluid retention disappears), the optimal dose of the ACE-inhibitor should be maintained followed by a beta-blocker. The dose of diuretic can be adjusted based on patient stability. To avoid hyperkalaemia, any potassium-sparing diuretic should be omitted from the diuretic regimen before introducing an ACE-inhibitor. However, an aldosterone antagonist may be added if hypokalaemia persists. Add a beta-blocker and titrate to target dosages used in large controlled trials (Table 13). Patients in sinus rhythm receiving cardiac glycosides and who have improved from severe to mild heart failure should continue cardiac glycoside therapy (recommendation page 1128) In patients who remain symptomatic and in patients who deteriorate, the addition of an ARB should be considered (recommendation page 1128).

Worsening heart failure (Figure 3)

Frequent causes of worsening heart failure are shown in Table 19. Patients in NYHA class III that have improved from NYHA class IV during the preceding 6 months or are currently NYHA class IV should receive low-dose spironolactone (12.5–50 mg daily recommendation page 1128). Cardiac glycosides are often added. Loop diuretics can be increased in dose, and combinations of diuretics (a loop diuretic with a thiazide) are often helpful. Cardiac resynchronization therapy should be considered if there is evidence of left ventricular dyssynchrony. Heart transplantation, coronary revascularization, aneurysmectory, or valve surgery may play a limited role.

End-stage heart failure (patients who persist in NYHA IV despite optimal treatment and proper diagnosis (Figure 4)

Patients should be (re)considered for heart transplantation if appropriate. In addition to the pharmacological treatments outlined in earlier sections, temporary inotropic support (intravenous sympathomimetic agents, dopaminergic agonists and/or phosphodiesterase agents) can be used in end-stage heart failure, but always should be considered as an interim approach to further treatment that will benefit the patient.

For patients on the waiting list for transplantation bridging procedures, circulatory support with intra-aortic balloon pumping or ventricular assist devices, haemofiltration or dialysis may sometimes be necessary. These should be used only in the context of a strategic plan for the long-term management of the patient.

Palliative treatment in terminal patients should always be considered and may include the use of opiates for the relief of symptoms.

Management of heart failure with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction

Although recent epidemiological studies suggest that in the elderly, the percentage of patients hospitalized with heart failure-like symptoms and PLVEF may be as high as 35–45%, there is uncertainty about the prevalence of diastolic dysfunction in patients with heart failure symptoms and a normal systolic function in the community. There is still little evidence from clinical trials or observational studies on how to treat heart failure with PLVEF.

Heart failure with PLVEF and heart failure due to diastolic dysfunction are not synonymous. The former diagnosis implies the evidence of preserved LVEF and not that left ventricular diastolic dysfunction has been demonstrated.

The diagnosis of isolated diastolic heart failure requires evidence of abnormal diastolic function, which may be difficult to assess. Precipitating factors should be identified and corrected, in particular tachy-arrhythmias should be prevented and sinus rhythm restored whenever possible. Rate control is important. Treatment approach is similar to patients without heart failure.106

Pharmacological therapy of heart failure with PLVEF or diastolic dysfunction

The following recommendations are largely speculative because of the limited data available in patients with PLVEF or diastolic dysfunction (in general, Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C).

There is no clear evidence that patients with primary diastolic heart failure benefit from any specific drug regimen.

ACE-inhibitors may improve relaxation and cardiac distensibility directly and may have long-term effects through their anti-hypertensive effects and regression of hypertrophy and fibrosis.

Diuretics may be necessary when episodes with fluid overload are present, but should be used cautiously so as not to lower preload excessively and thereby reduce stroke volume and cardiac output.

Beta-blockade could be instituted to lower heart rate and increase the diastolic filling period.

Verapamil-type calcium antagonists may be used for the same reason.107 Some studies with verapamil have shown a functional improvement in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.108

A high dose of an ARB may reduce hospitalizations.109

Heart failure treatment in the elderly

Heart failure occurs predominantly among elderly patients with a median age of about 75 years in community studies. Ageing is frequently associated with co-morbidity. Frequent concomitant diseases are hypertension, renal failure, obstructive lung disease, diabetes, stroke, arthritis, and anaemia. Such patients also receive multiple drugs, which includes the risk of unwanted interactions and may reduce compliance. In general, these patients in general have been excluded from randomized trials. Relief of symptoms rather than prolongation of life may be the most important goal of treatment for many older patients.

ACE-inhibitors and ARBs

ACE-inhibitors and ARBs are effective and well-tolerated in elderly patients in general.

Diuretic therapy

In the elderly, thiazides are often ineffective because of reduced glomerular filtration rate. In elderly patients, hyperkalaemia is more frequently seen with a combination of aldosterone antagonsist and ACE-inhibitors or NSAIDs and coxibs.

Beta-blockers

Beta-blocking agents are surprisingly well tolerated in the elderly if patients with such contraindications as sick sinus node, AV-block and obstructive lung disease are excluded. Beta-blockade should not be withheld because of increasing age alone.

Cardiac glycosides

Elderly patients may be more susceptible to adverse effects of digoxin. Initially, low dosages are recommended in patients with elevated serum creatinine.

Vasodilator agents

Venodilating drugs, such as nitrates and the arterial dilator hydralazine and the combination of these drugs, should be administered carefully because of the risk of hypotension.

Arrhythmias

It is essential to recognize and correct precipitating factors for arrhythmias, improve cardiac function and reduce neuro-endocrine activation with beta-blockade, ACE inhibition, and possibly, aldosterone receptor antagonists (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C).

Ventricular arrhythmias

In patients with ventricular arrhythmias, the use of anti-arrhythmic agents is only justified in patients with severe, symptomatic, sustained ventricular tachycardias and where amiodarone should be the preferred agent (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B).87,89

ICD implantation is indicated in patients with heart failure and with life threatening ventricular arrhythmias (i.e. ventricular fibrillation or sustained ventricular tachycardia) and in selected patients at high risk of sudden death (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A).95,96,110–112

Atrial fibrillation

For persistent (non-self-terminating) atrial fibrillation, electrical cardioversion could be considered, although its success rate may depend on the duration of atrial fibrillation and left atrial size (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B).

In patients with atrial fibrillation and heart failure and/or depressed left ventricular function, the use of anti-arrhythmic therapy to maintain sinus rhythm should be restricted to amiodarone (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C) and, if available, to dofetilide (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B).113

In asymptomatic patients beta-blockade, digitalis glycosides or the combination may be considered for control of ventricular rate (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence B). In symptomatic patients with systolic dysfunction digitalis glycosides are the first choice (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C). In PLVEF, verapamil can be considered (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence C).

Anti-coagulation in persistent atrial fibrillation with warfarin should always be considered unless contraindicated (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C).

Management of acute atrial fibrillation is not depending on previous heart failure or not. Treatment strategy is depending on symptoms and haemodynamic stability. For options see.106

Symptomatic systolic left ventricular dysfunction and concomitant angina or hypertension

Specific recommendations in addition to general treatment for heart failure because of systolic left ventricular dysfunction. If angina is present

optimize existing therapy, e.g. beta-blockade

add long-acting nitrates

if not successful, add amlodipine or felodipine

consider coronary revascularization.

If hypertension is present

optimize the dose of ACE-inhibitors, beta-blocking agents, and diuretics.40

add spironolactone or ARBs if not present already

if not successful, try second generation dihydropyridine derivatives.

Care and follow-up

See also Table 20.

An organized system of specialist heart failure care improves symptoms and reduces hospitalizations (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence A) and mortality (Class of recommendation IIa, level of evidence B) of patients with heart failure.71,114–118

It is likely that the optimal model will depend on local circumstances and resources and whether the model is designed for specific sub-groups of patients (e.g. severity of heart failure, age, co-morbidity, and left ventricular systolic dysfunction) or the whole heart failure population (Class of recommendation I, level of evidence C).119–122

Figure 1 Relationship between cardiac dysfunction, heart failure, and heart failure rendered asymptomatic.

Figure 2 Algorithm for the diagnosis of heart failure or left ventricular dysfunction.

Figure 3 The three filling patterns ‘impaired relaxation’, ‘pseudonormalised filling’, and ‘restrictive filling’ represent mild, moderate, and severe diastolic dysfunction, respectively.37

Figure 4 Pharmacological therapy of symptomatic CHF that is equally systolic left ventricular dysfunction. The algorithm should primarily be viewed as an example of how decisions on therapy can be made depending on the progression of heart failure severity. A patient in NYHA Class II can be followed with proposals of decision-making steps. Individual adjustments must be taken into consideration.

Definition of heart failure

| I. Symptoms of heart failure (at rest or during exercise) |

| and |

| III. Objective evidence (preferably by echocardiography) of cardiac dysfunction (systolic and/or diastolic) (at rest) and (in cases where the diagnosis is in doubt) |

| and |

| III. Response to treatment directed towards heart failure |

| I. Symptoms of heart failure (at rest or during exercise) |

| and |

| III. Objective evidence (preferably by echocardiography) of cardiac dysfunction (systolic and/or diastolic) (at rest) and (in cases where the diagnosis is in doubt) |

| and |

| III. Response to treatment directed towards heart failure |

Criteria I. and II. should be fulfilled in all cases.

Definition of heart failure

| I. Symptoms of heart failure (at rest or during exercise) |

| and |

| III. Objective evidence (preferably by echocardiography) of cardiac dysfunction (systolic and/or diastolic) (at rest) and (in cases where the diagnosis is in doubt) |

| and |

| III. Response to treatment directed towards heart failure |

| I. Symptoms of heart failure (at rest or during exercise) |

| and |

| III. Objective evidence (preferably by echocardiography) of cardiac dysfunction (systolic and/or diastolic) (at rest) and (in cases where the diagnosis is in doubt) |

| and |

| III. Response to treatment directed towards heart failure |

Criteria I. and II. should be fulfilled in all cases.

New York Heart Association classification of heart failure

| Class I No limitation: ordinary physical exercise does not cause undue fatigue, dyspnoea, or palpitations |

| Class II Slight limitation of physical activity: comfortable at rest but ordinary activity results in fatigue, palpitations, or dyspnoea |

| Class III Marked limitation of physical activity: comfortable at rest but less than ordinary activity results in symptoms |

| Class IV Unable to carry out any physical activity without discomfort: symptoms of heart failure are present even at rest with increased discomfort with any physical activity |

| Class I No limitation: ordinary physical exercise does not cause undue fatigue, dyspnoea, or palpitations |

| Class II Slight limitation of physical activity: comfortable at rest but ordinary activity results in fatigue, palpitations, or dyspnoea |

| Class III Marked limitation of physical activity: comfortable at rest but less than ordinary activity results in symptoms |

| Class IV Unable to carry out any physical activity without discomfort: symptoms of heart failure are present even at rest with increased discomfort with any physical activity |

New York Heart Association classification of heart failure

| Class I No limitation: ordinary physical exercise does not cause undue fatigue, dyspnoea, or palpitations |

| Class II Slight limitation of physical activity: comfortable at rest but ordinary activity results in fatigue, palpitations, or dyspnoea |

| Class III Marked limitation of physical activity: comfortable at rest but less than ordinary activity results in symptoms |

| Class IV Unable to carry out any physical activity without discomfort: symptoms of heart failure are present even at rest with increased discomfort with any physical activity |

| Class I No limitation: ordinary physical exercise does not cause undue fatigue, dyspnoea, or palpitations |

| Class II Slight limitation of physical activity: comfortable at rest but ordinary activity results in fatigue, palpitations, or dyspnoea |

| Class III Marked limitation of physical activity: comfortable at rest but less than ordinary activity results in symptoms |

| Class IV Unable to carry out any physical activity without discomfort: symptoms of heart failure are present even at rest with increased discomfort with any physical activity |

Assessments to be performed routinely to establish the presence and likely cause of heart failure

| Assessments . | Diagnosis of heart failure . | Suggests alternative or additional diagnosis . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | Necessary for . | Supports . | Opposes . | . |