-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Fraser Macfarlane, Sara Shaw, Trisha Greenhalgh, Yvonne H Carter, General practices as emergent research organizations: a qualitative study into organizational development, Family Practice, Volume 22, Issue 3, June 2005, Pages 298–304, https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmi011

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Background. An increasing proportion of research in primary care is locally undertaken in designated research practices. Capacity building to support high quality research at these grass roots is urgently needed and is a government priority. There is little previously published research on the process by which GP practices develop as research organizations or on their specific support needs at organizational level.

Methods. Using in-depth qualitative interviews with 28 key informants in 11 research practices across the UK, we explored their historical accounts of the development of research activity. We analysed the data with reference to contemporary theories of organizational development.

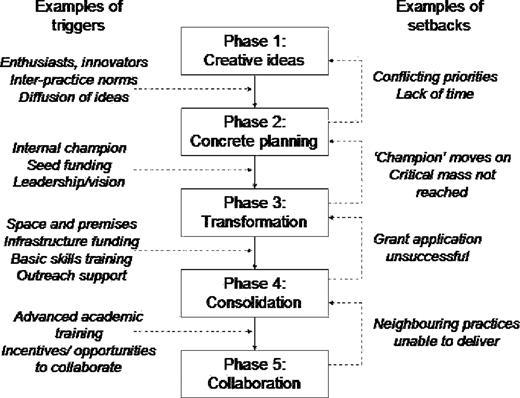

Results. Participants identified a number of key events and processes, which allowed us to produce a five-phase model of practice development in relation to research activity (creative energy, concrete planning, transformation/differentiation, consolidation and collaboration). Movement between these phases was not linear or continuous, but showed emergent and adaptive properties in which specific triggers and set-backs were often critical.

Conclusion. This developmental model challenges previous categorical taxonomies of research practices. It forms a theory-driven framework for providing appropriate support at the grass roots of primary care research, based on the practice's phase of development and the nature of external triggers and potential setbacks. Our findings have important implications for the strategic development of practice-based research in the UK, and could serve as a model for the wider international community.

Macfarlane F, Shaw S, Greenhalgh T and Carter YH. General practices as emergent research organizations: a qualitative study into organizational development. Family Practice 2005; 22: 298–304.

Introduction

Community-based research is a political priority in the UK, but until recently, primary care lacked both the capacity and the culture to support high-quality research.1 A Department of Health document published in 2002 sets out official policy, including the statutory requirement for all primary care trusts (PCTs) to develop a research role; structural arrangements for implementing research management and governance (RM&G); identification of funding streams; and workforce development issues.2 Professional and academic bodies have endorsed and supported these policies through various training and accreditation programmes.3 But there has been relatively little research so far into the impact of these policies on NHS organizations and the process by which research capacity develops (or fails to develop) at the grass roots.

This paper reports a study, undertaken in partnership with the Medical Research Council General Practice Research Framework (MRC–GPRF), which explored the development of GP research practices. Our aim was to identify key structural, developmental and environmental characteristics associated with successful and sustained involvement in research, and thereby inform a national strategy for research capacity-building in primary care. With the need for high quality primary care research increasingly recognised elsewhere in the world,4 we envisage that transferable lessons from our study may also inform international development.

Methods

We sought to produce an in-depth picture of the development of research in a range of GP practices. We selected a maximum variety sample of 18 practices from the MRC–GPRF database using the stratification criteria set out in Box 1.

Geographical location: rural, urban and inner-city.

Practice size: small (1–2 partners), medium (3–4 partners) and large practices (5+ partners).

Educational activity: teaching and non-teaching; vocational and undergraduate.

Deprivation indices: high and low Jarman scores.

Organizational history: ex-fundholding and non-fundholding.

Length of research experience: from involvement in a single research project to five or more.

Another selection criterion was location within eight PCT localities whose involvement in research management and governance (RM&G) we were evaluating for a separate study (this gave a population of 110 practices out of the overall total of approximately 1100 MRC–GPRF practices).8 This allowed us to interpret our data in the light of our wider knowledge of the extent of local support for primary care research and the structures and systems that were emerging for RM&G.

We obtained ethical approval from the Eastern Region MREC. We constructed a preliminary list of interview themes from an extensive review of the literature, and modified these in response to feedback by an expert reference group appointed by the Department of Health (details available from authors). The final list of prompts is shown in Box 2. Interviews took place from March– May 2003. We sought face-to-face interviews with key staff in each practice—generally a lead GP, a research nurse, and a practice manager or administrator. We audiotaped interviews, except for three occasions in which consent to record was not given, when the interviewer took detailed notes and typed them up immediately afterwards.

Individual's motivation and journey to become involved in research.

Research training/support available and impact on researchers.

Practicalities and logistics of research in general practice including engaging partners and colleagues, investment in infrastructure and the impact of research on the practice.

How the practice has developed as a research practice including linking with surrounding research infrastructure, development of strategy or plans for research, major milestones or “casualties”.

The practice's culture and how this may have helped or hindered research activities.

The impact being a research practice has had on the public and patients' perceptions of the practice.

Experience of research accreditation/assessment schemes and benchmarking research activity.

Practice and researcher characteristics.

We transcribed all taped interviews in full, and annotated them with contemporaneous field notes. Two researchers (FM and SS) independently analysed all transcripts using an adaptation of Richie and Spencer's framework method.5 We extracted a list of key themes, developed an initial coding framework, charted the data on a matrix based on this framework, and modified the matrix iteratively as we added more data. FM and SS presented their analysis to the wider research team before finalising the matrix. Discrepancies in interpretation were discussed and led us to identify additional over-arching themes and refine the categories within them. Our detailed analysis of the rich qualitative data allowed us to produce a tentative explanatory model of how GP practices become involved in research, and how this involvement changes over time. We compared this model with prevailing models of (and assumptions about) the organizational aspects of primary care research that we had identified in our literature review.6 We explored key discrepancies through discussion and by further analysis of our primary data, and concluded that a new model was needed to explain our data.7 We also compared the themes identified in this study with data from our earlier qualitative study that looked at RM&G activity at PCT level.8

Results

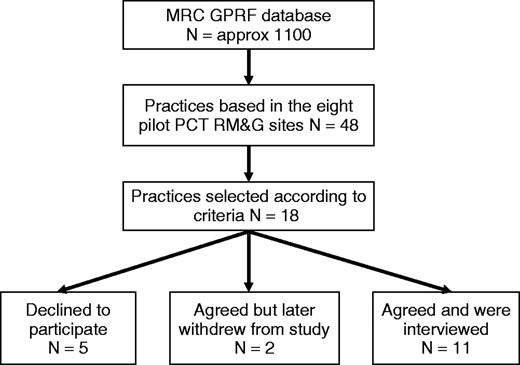

The recruitment of practices is summarized in Figure 1. We interviewed 7 lead GPs, 4 other GPs, 10 nurses, 1 research co-ordinator and 6 managers. Further details of individual participants are available from the authors. The 11 practices that participated in the study did not differ systematically from the 7 that did not in terms of the stratification criteria listed above. The reason for non-participation given by all practices was lack of time.

Overview of findings

The 11 practices represented the full range of selection criteria (large/small, urban/rural and so on); their involvement in research varied from minor activity (e.g. recruiting patients to be entered into trials run elsewhere) to one practice that had secured major grant funding and was co-ordinating multi-practice projects. Some but not all had well-established research infrastructure.

In contrast to the generally accepted taxonomy that there are distinct ‘types’ of research general practice—(occasional) ‘collaborators’ and ‘investigator-led’3—our data suggested that all research practices (and aspiring research practices) can be mapped to a single model of organizational development comprising a number of overlapping phases (Fig. 2). We found evidence that practices move broadly through these phases, but that movement through them is rarely predictable or linear. Rather, they can get ‘stuck’ in one phase and/or slip back and forth between phases, and these movements are often triggered by specific internal and/or external influences. Furthermore, practices' research decisions are often necessarily reactive (responding adaptively to external events such as the introduction of new national policies) rather than strategically proactive. We consider the different phases and influences below.

Phase 1: creative energy

Most participants identified research involvement as beginning when one GP began to undertake small, generally unfunded, ‘ad hoc’ research projects (described by one as “quasi-audits”). In a few cases, the trigger had been an invitation from the MRC–GPRF to participate in one of their trials, which brought a small but tangible income stream for a designated piece of work as well as assigning a temporary research nurse to the practice.

Participants used expressions like “having a go at it” and “jumping in at the deep end” when talking about this phase. Strong motivation and interest was present from the outset, but a planned approach to training and personal development for research generally came later. The enthusiasm of the innovator was sometimes infectious, especially if that individual was seen as a leader or role model. More commonly, research as one partner's side interest was initially perceived by other partners as diverting the practice from its main line of business, and tensions were common (especially in relation to potential loss of practice income).“I think there's some gap in knowledge. If a GP has a systematic approach and finds out what are the factors which are hindering improvement in asthma treatment. Obviously it could be different factors. It could be the drug, it could be the patient, it could be other environmental factors which would influence the treatment and the management. At the time it was the WISDOM Trial. I had another practice nurse. She was probably enthusiastic and she agreed that yes we should do something on asthma because asthma is another problem in the inner city practice.” (Interview 10, lead GP in small practice undertaking occasional collaborative studies)

This early phase had often led to isolation of the enthusiast from practice colleagues. All participants, but especially nurses, talked about the importance of developing interpersonal support networks with like-minded colleagues outside the practice.

Phase 2: concrete planning

Participants in established research practices could look back and identify a phase in which the practice began to move beyond ‘ad hoc’ projects and plan strategically for its future involvement in research. This shift was almost always credited to a particular champion within the practice, whose success in moving the practice to a more established phase was variously attributed to skill, interest, leadership, and political ‘clout’.

As Figure 2 shows, the move from Phase 1 to Phase 2 often resulted from particular triggers, such as a moderate sized research grant, the emergence of an active local research network, or a training course in the principles, practicalities and potential of research. Another critical influence in moving to the concrete planning phase was inter-practice norms and fashions (research being seen as the ‘thing to do’ in forward-looking practices), often transmitted through the informal social networks that linked practices within a locality.“Research started with the previous senior partner. Recognising the importance of research in general practice, he invested heavily in data management facilities and tried to push forward the agenda on research.” (Interview 07, lead GP in a well-established research practice)

Some practices had not moved beyond the ‘creative energy’ phase—or had slipped back into this phase after one successful project. These practices were continuing with a low level of research activity and in some instances were well poised to respond to another trigger if grant funding or other incentives came their way.“I suspect because various other surgeries had done it and they'd obviously discussed amongst themselves, would it be advantageous to do, we wondered what we would get out of it. What inputs would be needed and, from the patients' point of view, would it help?” (Interview 22, research nurse in small practice undertaking occasional collaborative studies)

Phase 3: transformation/differentiation

Participants in established research practices identified a phase during which their practice had followed through their plans and undergone transformation into an organization with a new culture and a dedicated infrastructure for supporting research. This phase was universally perceived as a period of long, hard work, associated with major changes in practice ethos, administrative systems, roles, and the organization's collective knowledge and skills base. The challenges of leading a rapidly expanding research organization were clearly considerable, requiring effort on many fronts—such as recruiting, training and retaining staff; writing grant applications; overseeing alterations in physical space (perhaps even moving premises); and liasing effectively with partners and colleagues to manage the change.

The transformation phase was characterized by two key developments in the organizational knowledge base: theoretical research knowledge (e.g. study design, statistics) and the ‘know-how’ of research administration, data collection and storage, troubleshooting, and quality control. A notable feature of this phase was that research gradually ceased to be attached to a named enthusiast within the practice and became defined more impersonally, through such features as the practice mission statement, budget lines, and the job descriptions of both academic and administrative staff.“I think the other thing that didn't help was the fact that we were very pushed for room in the practice and at one point I used to have to work in the surgery when it was empty at the time. I didn't know where we were based for a while, and all of this added pressure on me, so until everything like that was ironed out and the staff became more aware, it was a difficult transitional period at that point.” (Interview 06, research nurse in a well-established research practice)

Although explicit links between research and clinical activity were seen as important, developing a separate administrative infrastructure for research appeared to be essential as the volume of research activity grew. Participants bemoaned the rise in paperwork, and some described a feeling of loss of control as their research involvement grew beyond the entrepreneurial ‘one person show’ and inevitably acquired a bureaucracy and formality that had not been necessary in the early days.

Because of the introduction of new national and local policies, the transformation phase in many of the practices sampled in this study paralleled a more general expansion of research bureaucracy in healthcare, in particular the introduction of the Research Governance Framework9 and a requirement for all research active organizations to submit annual reports. The impetus for developing research infrastructure was thus partly internal (the need to account separately for research expenditure) and partly external (the requirements of funding bodies, governance structures, and accreditation schemes). A pivotal move in the practice's transformation was often the appointment of a separate research manager, administration team and work space within the practice.“We have a strategic plan, we have objectives—this is how we try and inform the staff when we collate our annual reports.” (Interview 02, research administrator in a developing research practice)

In the early days of development as a research practice, periods of discontinuity in research activity were almost inevitable when a ‘champion’ retired or moved practices, taking with them not only enthusiasm for research but a wealth of skills and knowledge that might take years to regain. But by the time transformation was complete, the practice generally had a critical mass of knowledge and know-how. It also tended to attract staff of high calibre who embraced the research ideal and brought in additional expertise.“I'm doing everything in the research process from beginning to end. Management co-ordination, facilitation, support … My role initially developed when I came in to support the GP researchers … Increasing it has become more management and co-ordination.” (Interview 02, research administrator in a developing research practice)

Phase 4: consolidation

In this phase, the practice consolidated its identity as a research practice and research became an integral part of ‘business as usual’, administratively differentiated and financially self-supporting. In many cases, the consolidation process was marked by a formal milestone such as achieving research practice status (becoming a 'Culyer' practice10) or obtaining the RCGP Primary Care Research Team Award,3 and/or by the award of the practice's first ‘big grant’.

A critical mass of core funding was frequently identified as being a sine qua non for maintaining ongoing research activity. ‘Culyer’ practices acknowledged the importance of ring-fenced funding for infrastructure and staff, which gave them time, space and confidence to bid for additional support on a project by project basis. In contrast, practices that lacked core infrastructure funding felt ‘stuck’:“People recognise the practice's name from our research activity and publications. People say ‘Oh, XXX Practice, I noticed your paper in the journal’.” (Interview 02, research manager in a developing research practice)

Several participants felt that another prerequisite for remaining viable in research was practice size; although it was hard to quantify this exactly. Below a certain size, they felt, it would be impossible to maintain research expertise and know-how or to sustain an efficient division of labour within the practice. They also alluded to the need for sufficient spare financial and administrative capacity to buffer the turbulence of any non-core activities.“We've got publications, we've got grants, our biggest problem is that we've got small grants and haven't moved into that higher layer.” (Interview 01, lead GP in a developing research practice)

In consolidation phase, research was no longer seen as interfering with clinical work but as enhancing it both directly (by feeding into variously clinical decision making, quality improvement and clinical governance) and indirectly (by introducing variety, raising motivation, enhancing professional identify, and reducing burn-out). The consolidation phase was associated with a palpable sense of organizational as well as individual achievement and pride. Participants talked about the practice as having gained status—using expressions like “cutting edge”. Being active in research was seen as a way of ensuring the effective recruitment of high quality professional staff and of providing a wide range of development opportunities for all staff.

Phase 5: collaboration and linkage

The collaboration phase is not synonymous with (though it often involves) multi-practice collaborative research. It is the phase in which a mature research practice, while still undertaking research on its own behalf, actively links in with the wider research economy including other practices, research support units, acute trusts and social service researchers, and, through these, begins to contribute to the strategic development of research locally and nationally.

An early feature of this phase was the development of consolidated links (rather than occasional interaction) with research support and/or academic units. Even when they had had extensive research training themselves, a number of participants mentioned the critical importance of having experts available to help with operationalizing these principles in the design of a study, the completion of a grant application, or the analysis of data. Sometimes (though relatively rarely) such links led to advanced academic training for someone within the practice.“To pick up big high-level grants is very difficult, but to pick up charitable funding is something we're looking at now, and we've had a little bit of charitable funding, and more often now we're going into large grant applications for SDO type bids with the university but with quite a large contingent of our research staff on that.” (Interview 07, lead GP in a developing research practice)

“I thought that on a professional level, talking about how one develops the profession itself, there is, I think, a need to encourage all GPs to believe in the research ethic and to regard research as being a natural accompaniment to the work that we do.” (Interview 18, senior partner (non-researcher) in a well-established research practice)

Participants also saw collaboration with academic units as going hand in hand with further expansion of research activity. The collaborative links forged between Phase 5 practices in relation to research also enabled closer collaboration on local clinical issues and exchange of ideas for best practice. Lead researchers in these practices tended to talk not merely about research development within their own practice, but about research priorities and capacity building more generally.

Many participants in this study felt that current Department of Health policy was forcing them to collaborate on research projects. Some felt strongly that coercing practices to collaborate on particular projects rather than simply promoting informal linkages and networking could be counterproductive, especially amongst practices who were not yet "ready" for a collaborative approach.

We found little evidence in this study that participants were forging closer links with PCTs, which from April 2003 held legal responsibility for local RM&G arrangements. Most participants felt that the individual practices knew more about the local (and national) research agenda than their PCT, perhaps because at the time of the study this research role was very new and PCTs were getting to grips with recent restructuring. Participants were also concerned that there was a mismatch of research priorities, with practices having a primary care research focus while PCTs would naturally take a more public health (“needs assessment”) focus.

Discussion

This study challenges previously published organizational models of practice-based research activity.3 As Figure 2 shows, our empirical findings strongly support a developmental and adaptive (rather than fixed and categorical) classification of GP practices as research organizations. A limitation of this study is that we used retrospective narrative accounts rather than prospective observation to gain insight into the longitudinal dimension of practice development. We hope to return to these practices after a time interval and obtain further data to test the hypothesis presented here.

The MRC–GPRF does not include all research active practices, nor are these practices necessarily representative of the research community, though the MRC framework covers a patient population representative of the UK as a whole. Because membership of the MRC–GPRF depends on meeting an entry standard, it is likely that the research practices sampled for this study are better organized, better funded and more successful than research practices as a whole. We have recently commenced a new study into the development (and non-development) of research in non-GPRF research practices.

The development of research in general practice and the role of primary care research networks and PCTs in developing this has been reviewed elsewhere.11,12 Our findings suggest that if research is to develop in general practice, external linkages with PCTs, other practices, academic departments and primary care research networks will need to be developed. Indeed, these linkages seem to play a crucial role in the movement between different phases of our developmental model.

The organizational development literature includes a number of dynamic models of change and transformation. Greiner introduced the concept of the “organizational life cycle”, comprising birth, early development, maturity, decline and death, each characterized by different organizational processes.6 In focussing particularly on expanding small organizations, he identified five overlapping growth stages—creativity, direction, delegation, co-ordination and collaboration—and suggested that the shift between any of these stages is characterized by distinct periods of crisis.

Van de Ven et al. have criticised life-cycle and other staged models as linear and deterministic.7 They propose an ‘organic’ model of organizational innovation, with an initiation phase characterized by the creative generation of ideas, followed by ‘shocks’ (triggers that propel the organization into action), and resource plans to ensure that the innovation can be developed. There follows a development phase, in which real efforts are made to transform the idea into something concrete, punctuated by pivotal ‘setbacks’ and ‘surprises’, and finally a consolidation phase in which the innovation becomes part of business as usual. A key feature of this model is the movement back and forth between phases as a complex innovation unfolds within an organization. Ideas may go through an initial consideration period before being shelved for months or years. Shocks may make particular innovations redundant—or especially urgent. Restructuring may be needed, and require new resource plans. Micropolitical tensions and forces within the organization can be critical.

Both these models have informed our own five-phase model (Fig. 2), in which the practice moves erratically from ‘creative energy’ driven by individual enthusiasm to a mature research organization embedded in a wider collaborative network of similar and supporting organizations. Our findings also confirm a number of principles of effective innovation in health service organizations,13 including the powerful influence of ‘norm-setting’ organizations on organizational-level adoption decisions; the role of boundary spanners (people with significant interpersonal ties beyond the organisation) in capturing ideas from outside and feeding them into the organization's knowledge-creation cycle; the role of internal champions in driving through innovation within an organization; and the significant influence of structural determinants (size, slack resources, internal differentiation and decentralisation of decision making) on organizational innovativeness.

Our findings highlight the need to focus on the transitions between development phases rather than just the phases themselves.14 One critical transition is from the early creative phase (in which research activity is spontaneous, exploratory, strongly linked to a particular individual and often financially precarious) to a more mature, structured and differentiated phase (in which research activity is a core property of the organization itself). This ‘formalization transition’ is highlighted in the organizational literature as a crisis point for developing organizations, often associated with a fall-off in performance and prolonged internal conflict.15

A key implication from this study is that the needs of research practices differ according to their phase of development, and, therefore, support should take different forms depending on the phase of development. Indeed, an external ‘push’ that is not linked to the practice's phase of development may actually be damaging, as with the requirement to formally collaborate with other practices on research studies—which our findings suggest is helpful for mature research practices but tends to stifle development in practices who are still at Phase 1 or 2. Table 1 offers some preliminary recommendations, which we hope will be considered further when strategic decisions are made both within and outside of the UK on the nature and focus of support for research capacity-building in primary care.

Implications of our model for supporting research practices at the grass roots

| Phase . | Critical features of success (or failure) in this phase . | Recommendations for supporting practices in this phase . |

|---|---|---|

| I: creative energy | Organizational boundary spanners | Informal networking opportunities for motivated individuals e.g. 'open space' events |

| Inter-organizational norm-setting | Protected time for the individual research lead e.g. a paid ‘research session’ | |

| Informal networks between like-minded individuals | ||

| II: concrete planning | All members of the practice decide to go for research and pull together to get an initial strategy | Facilitation, infrastructure support, participation in accreditation schemes such as PCRTA |

| III: transformation | Hard work | Training: Core research skills; project management skills |

| ‘Lots of processes’ | Initiatives to support continuity of core staff | |

| Premises/space | ||

| Staff training | ||

| Staff development skills | ||

| Pump-priming grants | ||

| Premises development grants | ||

| “Beacon” visits for acquisition of tacit (‘how-to’) knowledge | ||

| IV: consolidation | Getting a big grant | Outreach support from academic unit |

| Getting Culyer status | Incentives/support to get accredited | |

| V: collaboration | Informal inter-organizational networking | Inter-organizational networking and linkage activities adopt a Collaborative |

| Inter-practice collaboration on specific research projects | Quality Improvement approach | |

| Close linkage with research support units and/or academic departments | Project management and research input from inter-practice research support unit | |

| Joint academic-service appointments |

| Phase . | Critical features of success (or failure) in this phase . | Recommendations for supporting practices in this phase . |

|---|---|---|

| I: creative energy | Organizational boundary spanners | Informal networking opportunities for motivated individuals e.g. 'open space' events |

| Inter-organizational norm-setting | Protected time for the individual research lead e.g. a paid ‘research session’ | |

| Informal networks between like-minded individuals | ||

| II: concrete planning | All members of the practice decide to go for research and pull together to get an initial strategy | Facilitation, infrastructure support, participation in accreditation schemes such as PCRTA |

| III: transformation | Hard work | Training: Core research skills; project management skills |

| ‘Lots of processes’ | Initiatives to support continuity of core staff | |

| Premises/space | ||

| Staff training | ||

| Staff development skills | ||

| Pump-priming grants | ||

| Premises development grants | ||

| “Beacon” visits for acquisition of tacit (‘how-to’) knowledge | ||

| IV: consolidation | Getting a big grant | Outreach support from academic unit |

| Getting Culyer status | Incentives/support to get accredited | |

| V: collaboration | Informal inter-organizational networking | Inter-organizational networking and linkage activities adopt a Collaborative |

| Inter-practice collaboration on specific research projects | Quality Improvement approach | |

| Close linkage with research support units and/or academic departments | Project management and research input from inter-practice research support unit | |

| Joint academic-service appointments |

Implications of our model for supporting research practices at the grass roots

| Phase . | Critical features of success (or failure) in this phase . | Recommendations for supporting practices in this phase . |

|---|---|---|

| I: creative energy | Organizational boundary spanners | Informal networking opportunities for motivated individuals e.g. 'open space' events |

| Inter-organizational norm-setting | Protected time for the individual research lead e.g. a paid ‘research session’ | |

| Informal networks between like-minded individuals | ||

| II: concrete planning | All members of the practice decide to go for research and pull together to get an initial strategy | Facilitation, infrastructure support, participation in accreditation schemes such as PCRTA |

| III: transformation | Hard work | Training: Core research skills; project management skills |

| ‘Lots of processes’ | Initiatives to support continuity of core staff | |

| Premises/space | ||

| Staff training | ||

| Staff development skills | ||

| Pump-priming grants | ||

| Premises development grants | ||

| “Beacon” visits for acquisition of tacit (‘how-to’) knowledge | ||

| IV: consolidation | Getting a big grant | Outreach support from academic unit |

| Getting Culyer status | Incentives/support to get accredited | |

| V: collaboration | Informal inter-organizational networking | Inter-organizational networking and linkage activities adopt a Collaborative |

| Inter-practice collaboration on specific research projects | Quality Improvement approach | |

| Close linkage with research support units and/or academic departments | Project management and research input from inter-practice research support unit | |

| Joint academic-service appointments |

| Phase . | Critical features of success (or failure) in this phase . | Recommendations for supporting practices in this phase . |

|---|---|---|

| I: creative energy | Organizational boundary spanners | Informal networking opportunities for motivated individuals e.g. 'open space' events |

| Inter-organizational norm-setting | Protected time for the individual research lead e.g. a paid ‘research session’ | |

| Informal networks between like-minded individuals | ||

| II: concrete planning | All members of the practice decide to go for research and pull together to get an initial strategy | Facilitation, infrastructure support, participation in accreditation schemes such as PCRTA |

| III: transformation | Hard work | Training: Core research skills; project management skills |

| ‘Lots of processes’ | Initiatives to support continuity of core staff | |

| Premises/space | ||

| Staff training | ||

| Staff development skills | ||

| Pump-priming grants | ||

| Premises development grants | ||

| “Beacon” visits for acquisition of tacit (‘how-to’) knowledge | ||

| IV: consolidation | Getting a big grant | Outreach support from academic unit |

| Getting Culyer status | Incentives/support to get accredited | |

| V: collaboration | Informal inter-organizational networking | Inter-organizational networking and linkage activities adopt a Collaborative |

| Inter-practice collaboration on specific research projects | Quality Improvement approach | |

| Close linkage with research support units and/or academic departments | Project management and research input from inter-practice research support unit | |

| Joint academic-service appointments |

Declaration

Funding: this research was funded by the Department of Health Research Capacity Development Programme. The views expressed in the paper represent those of the authors and not necessarily those of the funding body.

Ethical approval: ethical approval was obtained from the Eastern Region MREC.

Conflicts of interest: none.

Practices were selected and recruited with the help of the MRC General Practice Research Framework team.

References

Department of Health. Primary and Community Care Organisations—Research Management and Governance: Information for Primary Care Trusts. www.doh.gov.uk/research/rd3/nhsrandd/pctrm&gguidance.htm

Carter YH, Shaw S, Macfarlane F. Primary Care Research Team Assessment (PCRTA): development and evaluation. Occasional Paper Series no 81. London: Royal College of General Practitioners;

van Weel C. International research and the discipline of family medicine.

Ritchie J, Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis in applied policy research. In Bryman A, Burgess R (eds). Analyzing Qualitative Data. London: Routledge;

Greiner L. Evolution and revolution as organisations grow.

Van de Ven AH, Polley DE, Garud R, Venkataraman S. The Innovation Journey. Oxford: Oxford University Press;

Shaw S, Macfarlane F, Greaves C, Carter YH. Developing research management and governance arrangements in primary care organisations: transferable learning from a qualitative evaluation of UK pilot sites.

Department of Health. Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. London: Department of Health;

Carter YH. Funding research in primary care: is Culyer the remedy?

Department of Health. Joint Ministerial Review (JMR) of the role of Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) in relation to learning and research in the new NHS. London: Department of Health;

Evans D, Exworthy, M, Peckham, S, Robinson, R. Primary care research networks—Report to the NHS Executive South and West Research and Development Directorate. Southampton: Institute for Health Policy Studies, University of Southampton;

Greenhalgh T, Robert G, Macfarlane F, Bate P, Kyriakidou O. Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: systematic review and recommendations.

Kimberly J, Miles R. The Organisational Life Cycle: Issues in the Creation, transformation, and Decline of Organisations. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers;

Author notes

aSchool of Management, University of Surrey, bDepartment of Primary Care and Population Sciences, University College London and cWarwick Medical School, The University of Warwick, UK