-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Anne Kennedy, Linda Gask, Anne Rogers, Training professionals to engage with and promote self-management, Health Education Research, Volume 20, Issue 5, October 2005, Pages 567–578, https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyh018

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

We have set out to investigate an approach to improve patients' ability to self-manage chronic illness. For effective health care in chronic disease, we believe patients need to work in partnership with their doctor; patient-centred consultations are one way to achieve this. This report describes our experience of training specialists in gastroenterology to consult in a patient-centred style as part of a complex self-management intervention in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) involving 700 patients with established inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) attending outpatient clinics. The training session aimed to provide specialists from nine randomly selected intervention sites with the basic skills to carry out the intervention. The training lasted 2 hours, and included background on the research and intervention, a demonstration video, role-play, and video-feedback training. The main findings of the RCT are presented (service use, enablement and satisfaction), and discussed in the light of the views of consultants and patients on the experience of putting the training into practice. The findings of our study confirm and highlight the value of training in patient-centred communication and its potential for promoting self-management effects; the training proved effective in enabling consultants in gastroenterology to establish guided self-management in patients with IBD.

Introduction

Self-management is increasingly recognized as part of secondary prevention and a way of reducing the burden of chronic illness. Recognition of the importance of self-management as a public health intervention is evident in health policy. The Expert Patients Programme (Department of Health, 2001), which includes the delivery of self-management training, is the UK government response to recognizing the role of patients in managing chronic illness in a way which promotes a sense of well-being and optimizes a person's ability to live as well as possible with a particular chronic condition. The training needs of health professionals who come into contact with self-managing ‘expert patients’ also need to be considered.

Patients' encounters with health care professionals are both sporadic and ongoing, vary in intensity, and increasingly involve an array of specialist and generalist practitioners. Whilst the vast majority of chronic disease management is usually conducted by the patient as part of their every day lives, consultations between patients and health care professionals provide a critical juncture for the exchange of information and decision making. The extent to which professionals are able to instigate and participate in effective communication is likely to make a difference to encouraging and supporting decisions and self-care actions which may enable patients to optimally manage their condition outside of health service settings. Whilst there is a considerable body of theories and evidence regarding medical education to teach techniques to elicit behavioural change in patients (e.g. smoking and alcohol-related problems) (Bandura, 1977; Janz and Becker, 1984; Rollnick et al., 1993; Prochaska and Velicer, 1997), there is as yet very little knowledge in how to educate health professionals in ways to enable their patients to self-manage. Doherty et al. (Doherty et al., 2000) developed a training programme to help staff working in diabetes care facilitate behaviour change and self-management. They defined the essential competencies staff needed, and found the most valued training methods were individual supervision and video examples. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) investigating the effect of education of clinicians on the health status of patients with asthma found that education which focused on changing specific aspects of physician behaviour led to more efficient and effective consultations; however, although health care utilization was reduced in the intervention group, the change was not significant (Clark et al., 1998).

For guided self-management to be successful, a positive patient/physician relationship has been shown to be a key factor (Coulter, 1997; Clark and Gong, 2000; Holman and Lorig, 2000). Building on the existing established relationships between patients and professionals working within the NHS may be one way of doing this – not least because this is where health care is most accessible to people from all social backgrounds. The paternalistic approach to long-term care where a health professional makes all the decisions about treatment and closely monitors the patient's progress is considered inappropriate for modern healthcare. A model which incorporates the development of increasing partnership working between patients and clinicians is viewed as more conducive to shared clinical decision making and disease management because patients with chronic conditions have been shown to find such a relationship more supportive (Thorne and Paterson, 2001) and patients do want to be directly involved in decision making (Coulter, 1997).

There are a number of reasons why the professional consultation is an appropriate context for developing self-management skills. In recent years there has been a key shift in the medical consultation from being ‘doctor-centred’ to ‘patient-centred’ (Stewart et al., 1995) Although the exact definition of patient-centredness varies, it includes consideration of psychological issues, understanding the patient as an individual, sharing control over decision making, and developing a long-term therapeutic relationship between patient and professional (Mead and Bower, 2000). Some of the skills required to increase patient involvement and patient-centredness have already been identified, and include broad professional attitudes (e.g. self-awareness) and specific consultation behaviours (e.g. use of open questions, expressions of empathy).

There is evidence that health care professionals can enable and support patients with chronic diseases to monitor their disease, adjust their treatment in response to changes and identify situations where medical intervention is advisable (Clark et al., 1998; Day, 2000; Robinson et al., 2001). Guided self-management involves the provision of a shared set of guidelines containing action plans designed to prevent disease activity and/or to alleviate symptoms. By providing the patient with a clear set of goals, guided self-management plans also give patients a basis for discussion and negotiation with the health provider, and a framework within which to understand their disease (Osman, 1996). The successful implementation of guided self-management requires: a mutual acceptance by patient and health professionals of the value of the advocated approach to care (Benbassat et al., 1998; Clark et al., 1998), time to explain the practical aspects involved (Woodcock et al., 1999; Kennedy and Rogers, 2002), a willingness to share information freely (Guadagnoli and Ward, 1998), and an understanding of the social, psychological and behavioural factors which influence patient concordance (Dixon-Woods, 2001; Thorne and Paterson, 2001).

We report here the nature and response of consultants to the training element of a guided self-management intervention for patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). The training took place within the broader context of a RCT of a complex intervention; one of the strategies was to train gastroenterology consultants in methods to promote self-management. This paper will give details of the training and present some of the study findings which relate to the training; main findings are reported elsewhere (Kennedy et al., 2004).

Methods

Study details

The intervention was based on a whole-systems approach (Kennedy and Rogers, 2001) to the introduction of self-management and included the following components:

Training consultants to provide a patient-centred approach to care.

Provision to patients of an information guidebook. Guidebooks on ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease were developed with patients prior to the study. Evaluation showed that most users place high value on their relationship with professionals and regard them as the most important source of information (Kennedy and Rogers, 2002). Thus, the utility and impact of patient information was thought to be enhanced if professionals were involved in the dissemination of, and use of, the guidebook jointly with patients.

Negotiation of a written self-management plan.

Patients offered direct access to making outpatient clinic appointments with no more fixed appointments once a self-management plan had been negotiated.

Description of main trial

The economic evaluation looked at health service resource use and assessed cost-effectiveness. Data was obtained at baseline through face-to-face interviews, and at 12 months from patient diaries, postal questionnaires and hospital medical records. Qualitative interviews undertaken at the end of the trial with 11 consultants and 28 patients focused on the processes underlying the outcomes and the themes relating to the training are outlined in Tables II and III (see below).

Trial design. A multi-centre trial with randomization by treatment centre. Nineteen hospitals were randomized to 10 control sites and nine intervention sites. Consultants from intervention sites received training before recruitment and introduced the intervention to eligible patients. Patients at the control sites were recruited and went on to have an ordinary consultation. Qualitative interviews were undertaken to obtain an in-depth understanding of patients' and consultants' experience of the intervention.

Setting. Follow-up outpatient clinics at 19 hospitals in the northwest of England.

Participants. Seven hundred (297 at intervention sites and 403 at control sites) patients were recruited who had established ulcerative colitis or Crohn's disease, were aged 16 and over, and were able to write English.

Main outcomes. The rates of hospital outpatient consultation, quality of life and acceptability to patients. Other clinical outcomes included anxiety and depression, patient enablement, patient satisfaction, flare-up duration, and the interval between relapse and treatment.

The project was approved by the North West region multi-centre research ethics committee (MREC 98/8/23).

The training

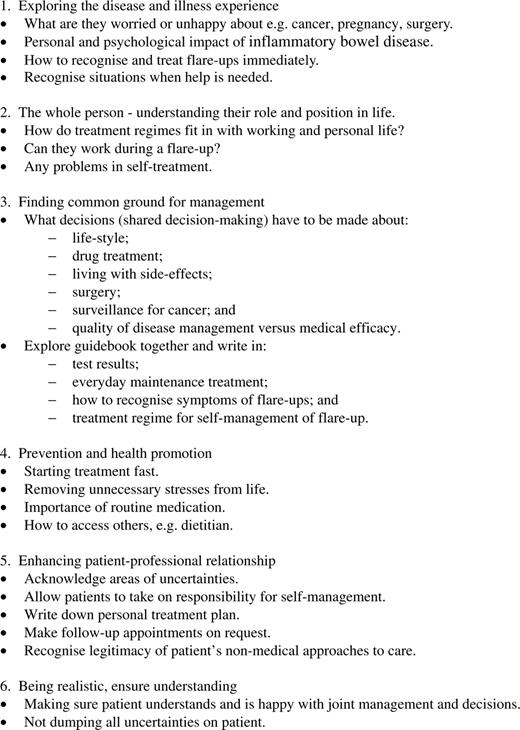

The training of consultants in gastroenterology to consult in a patient-centred style formed the initial stage of the trial. The aims of the training session were 2-fold—to fully recruit the specialists to the trial and to provide them with the basic skills that they would need to carry out the intervention. The learning techniques of role-play and video-feedback are established methods of developing consultation skills (Gask, 1998). Training encompassed the components of patient-centred medicine advocated by Stewart et al. (Stewart et al., 1995) and related them to self-management of IBD (see Figure 1). This framework was selected because it has been commonly referred to and used in medical education in terms of a biopsychosocial approach (Margalit et al., 2004).

For the purposes of participation in the trial, all 24 hospitals in the northwest of England with gastroenterology departments were approached, two sites did not want to take part in the study because of prior research commitments, two sites did not reply despite several approaches and one site did not commit to the study in time for inclusion. The 19 sites were randomized to nine intervention sites and 10 control sites. All members of the consultants' team for each of the nine intervention sites were invited to one of four training sessions led by an experienced expert in medical education (L. G.). A total of 24 team members attended, comprising 12 consultants, six specialist nurses, five specialist registrars and one secretary. It was ensured that all the consultants from each of the sites attended, as these were the individuals who would be delivering the intervention. They were asked to bring other members of their teams they felt would benefit from knowledge of the trial.

The training sessions lasted for 2 hours and included:

Use of a product champion (Stocking, 1985) (a respected Professor of Gastroenterology) to introduce the research and training team, and ‘sell’ the importance and relevance of the project.

Description of the background to the research, including the results of the successful pilot project (Robinson et al., 2001).

Description of the research and interventions.

A description of the skills necessary for working in a patient-centred style.

Demonstration video (Kennedy et al., 1999).

Role-play and video-feedback training.

Discussion.

Skills necessary to work in a patient-centred style

The two major components of a patient-centred consultation for IBD were taken to be:The fine details are outlined in Figure 1.

Addressing the impact of the disease on the patient.

Establishing with the patient what treatment works.

The skills consultants were instructed to use included:These skills were demonstrated to the participants using a previously recorded video of a model consultation. The video gives an example of an entire consultation between a patient with ulcerative colitis and a gastroenterologist. The consultation is patient-centred, and it demonstrates how self-management can be introduced and treatment options explored by using the guidebook.

Open-ended questions.

Picking up cues from patients.

Clarification.

Summarizing.

Checking out.

Collaborative approach to treatment.

The participants were then asked to pair-off and take part in a role-play, using a patient-centred consultation to introduce changes in management including: introduction of the guidebook, making a written management plan and enabling self-referral to the clinic. One pair's role-play was recorded on a video and used to aid discussion.

Participants were able to discuss their concerns about the trial and where possible, or necessary, adjustments were made to the protocol. Table I summarizes the views of the participants as recorded at the end of each training session. The sessions were viewed positively and showed slightly less enthusiasm for the role-play than for the other aspects of the training session. Participants felt the most important things they gained from the session were:

Opportunity to discuss practicalities of the trial.

Greater understanding of patient-centredness.

Discussion with peers about current consultation practice.

Potential impact of study on clinics.

Many participants thought the training session needed to be longer.

Opinions of participants at the patient-centred training sessions

. | Not at all . | . | . | . | Very Much . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 0 . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | |||

| Did you enjoy the training? | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 9 | |||

| Did you like the structure? | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the research background interesting? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 10 | |||

| Did you find the research instructions useful? | 0 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 9 | |||

| Did you find the video useful? | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the role play helpful? | 0 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the video review interesting? | 0 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 5 | |||

| Was the discussion at the end of benefit? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 12 | |||

| How actively involved were you during the evening? | 1 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 5 | |||

| Total | 1 | 10 | 34 | 98 | 71 | |||

| Percentage of total replies | 0.5 | 5 | 16 | 46 | 33 | |||

. | Not at all . | . | . | . | Very Much . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 0 . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | |||

| Did you enjoy the training? | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 9 | |||

| Did you like the structure? | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the research background interesting? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 10 | |||

| Did you find the research instructions useful? | 0 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 9 | |||

| Did you find the video useful? | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the role play helpful? | 0 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the video review interesting? | 0 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 5 | |||

| Was the discussion at the end of benefit? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 12 | |||

| How actively involved were you during the evening? | 1 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 5 | |||

| Total | 1 | 10 | 34 | 98 | 71 | |||

| Percentage of total replies | 0.5 | 5 | 16 | 46 | 33 | |||

Opinions of participants at the patient-centred training sessions

. | Not at all . | . | . | . | Very Much . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 0 . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | |||

| Did you enjoy the training? | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 9 | |||

| Did you like the structure? | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the research background interesting? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 10 | |||

| Did you find the research instructions useful? | 0 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 9 | |||

| Did you find the video useful? | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the role play helpful? | 0 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the video review interesting? | 0 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 5 | |||

| Was the discussion at the end of benefit? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 12 | |||

| How actively involved were you during the evening? | 1 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 5 | |||

| Total | 1 | 10 | 34 | 98 | 71 | |||

| Percentage of total replies | 0.5 | 5 | 16 | 46 | 33 | |||

. | Not at all . | . | . | . | Very Much . | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

. | 0 . | 1 . | 2 . | 3 . | 4 . | |||

| Did you enjoy the training? | 0 | 0 | 4 | 11 | 9 | |||

| Did you like the structure? | 0 | 0 | 4 | 13 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the research background interesting? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 10 | |||

| Did you find the research instructions useful? | 0 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 9 | |||

| Did you find the video useful? | 0 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the role play helpful? | 0 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 7 | |||

| Did you find the video review interesting? | 0 | 1 | 6 | 12 | 5 | |||

| Was the discussion at the end of benefit? | 0 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 12 | |||

| How actively involved were you during the evening? | 1 | 0 | 7 | 11 | 5 | |||

| Total | 1 | 10 | 34 | 98 | 71 | |||

| Percentage of total replies | 0.5 | 5 | 16 | 46 | 33 | |||

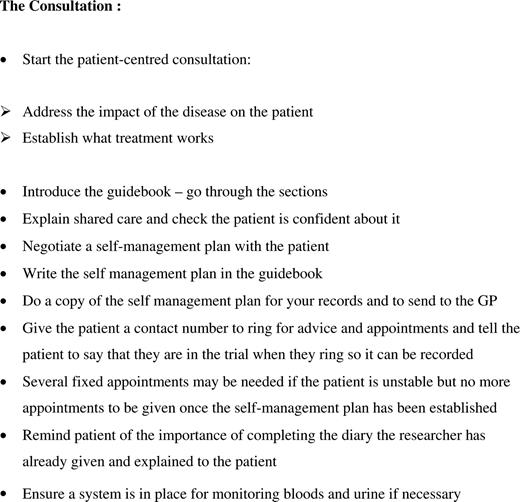

Timing of training

The training sessions for consultants and their teams took place after site randomization and before recruitment of patients. Consultants were given a one-page outline containing bullet points on how to conduct the patient-centred consultation which followed patient recruitment to the trial during outpatient clinics (see Figure 2). The guidebook was given to patients at the intervention sites during this recruitment consultation and the self-management plan was written into the record book.

Notes for consultants on how to conduct the intervention consultation.

Results

Details of trial methodology, outcome measures and results are published elsewhere (Kennedy et al., 2004). The main findings were that 1 year following the intervention, self-managing patients had made fewer hospital visits [difference −1.04, 95% confidence interval (CI) −1.43 to −0.65, P < 0.001] without any increase in the number of primary care visits and quality of life was maintained without evidence of anxiety about the programme. The two groups were similar with respect to satisfaction with consultations [measured using the Consultation Satisfaction Questionnaire (Baker, 1990)]. Immediately after the initial consultation, those who had undergone self-management training reported greater confidence in being able to cope with their condition [using the Patient Enablement Instrument (Howie et al., 1999), difference 0.90, 95% CI 0.12 to 1.68, P < 0.03]. More detailed qualitative analyses of the interviews have been undertaken looking at the themes of access and patient-centredness (Rogers et al., 2004, 2005). The qualitative results reported here are the themes related to the consultant training.

Transferring the principles of training into practice

One indicator of the success of translating the training into practice is indicated by the measure of enablement experienced by patients immediately after the intervention consultation. Patients in the intervention group were significantly more likely to report feeling enabled to cope with their condition than those in the control group (where consultants had not received the training). However, these effects appear not to have been sustained over a longer period and rates of overall satisfaction with the consultation did not improve significantly.

The qualitative results indicated some of the barriers to implementation, but organizational limitations constrained patient-centred aspects of the intervention for some. Table II summarizes the views of consultants. The patient-centred approach was felt to reflect their normal or ideal practice. Some respondents held the view that they were already committed to practise in a patient-centred way, so the training was not necessary for them, although some felt it might have been appropriate for less-experienced colleagues. This suggests that the principles of training might not, in the longer term, have bought about radical change in the way in which consultants communicated with patients. Although the intervention as outlined in the training sessions was seen as being operational in everyday health settings, there were important caveats; in particular, that the pressures of time of normal clinics were not considered. The main change in behaviour that the training required was to make time to allow a discursive and open consultation. The restricted time allocated for outpatient appointments prevented the full operationalization of the principles of training in this regard.

Summary of consultants' views on training

Theme . | Quote . |

|---|---|

| Adequacy of training for purposes of study | Training adequate |

| The training was fine, except that I realized that when I got down to a clinic you know, there are all sorts of pressures on you that tend to make you a little bit more pragmatic. [ID 5] | |

| Patient-centred aspect of training | Already patient-centred |

| I found it odd and a little offensive that the trainers assumed we needed reminding about patient-centred care and patient choice. Otherwise it was perfectly adequate. [ID 7] | |

| Resulting changes in consultation behaviour | Improved communication |

| So I was happy with the book—I was happy with the dialogue but I had very few comments from those that did come back, because the plan that we had agreed which was clearly written in the book. [ID 12] | |

| Clarifying patient's responsibilities | |

| I think the advantages are the ones that we‘ve alluded to, you know, the sense that the patients feel as if they’ve got a part of their treatment they feel their appointments are not wasted because they can come when there is something specific to achieve in the appointment and they also feel as if they have the information and the knowledge and the permission as it were to do things on their own and its all OK to do that, you know, some of them have done it anyway, but to make it all official if you like, it does give them proper power, whereas sometimes they come and sort of say ‘well I did take some Prednisolone last week’ and you say ‘that's fine, that's fine’ you know, whereas this is actually saying you do take this rather than saying you know you're quite naughty if they have done. [ID 5] | |

| Perceived outcomes for patients | Increased confidence to self-manage |

| It seemed to have fulfilled what they were expecting or what they would have liked to have happened and now it's been formalized, they're very pleased. It's helped them to ask more questions because they're more informed, and they've also got a contact number which reassures them, even though they used to have one in our old clinic anyway but I think now it's written down, you know this is who you contact and this is the number you ring gives them a lot of confidence. [ID 2] |

Theme . | Quote . |

|---|---|

| Adequacy of training for purposes of study | Training adequate |

| The training was fine, except that I realized that when I got down to a clinic you know, there are all sorts of pressures on you that tend to make you a little bit more pragmatic. [ID 5] | |

| Patient-centred aspect of training | Already patient-centred |

| I found it odd and a little offensive that the trainers assumed we needed reminding about patient-centred care and patient choice. Otherwise it was perfectly adequate. [ID 7] | |

| Resulting changes in consultation behaviour | Improved communication |

| So I was happy with the book—I was happy with the dialogue but I had very few comments from those that did come back, because the plan that we had agreed which was clearly written in the book. [ID 12] | |

| Clarifying patient's responsibilities | |

| I think the advantages are the ones that we‘ve alluded to, you know, the sense that the patients feel as if they’ve got a part of their treatment they feel their appointments are not wasted because they can come when there is something specific to achieve in the appointment and they also feel as if they have the information and the knowledge and the permission as it were to do things on their own and its all OK to do that, you know, some of them have done it anyway, but to make it all official if you like, it does give them proper power, whereas sometimes they come and sort of say ‘well I did take some Prednisolone last week’ and you say ‘that's fine, that's fine’ you know, whereas this is actually saying you do take this rather than saying you know you're quite naughty if they have done. [ID 5] | |

| Perceived outcomes for patients | Increased confidence to self-manage |

| It seemed to have fulfilled what they were expecting or what they would have liked to have happened and now it's been formalized, they're very pleased. It's helped them to ask more questions because they're more informed, and they've also got a contact number which reassures them, even though they used to have one in our old clinic anyway but I think now it's written down, you know this is who you contact and this is the number you ring gives them a lot of confidence. [ID 2] |

Summary of consultants' views on training

Theme . | Quote . |

|---|---|

| Adequacy of training for purposes of study | Training adequate |

| The training was fine, except that I realized that when I got down to a clinic you know, there are all sorts of pressures on you that tend to make you a little bit more pragmatic. [ID 5] | |

| Patient-centred aspect of training | Already patient-centred |

| I found it odd and a little offensive that the trainers assumed we needed reminding about patient-centred care and patient choice. Otherwise it was perfectly adequate. [ID 7] | |

| Resulting changes in consultation behaviour | Improved communication |

| So I was happy with the book—I was happy with the dialogue but I had very few comments from those that did come back, because the plan that we had agreed which was clearly written in the book. [ID 12] | |

| Clarifying patient's responsibilities | |

| I think the advantages are the ones that we‘ve alluded to, you know, the sense that the patients feel as if they’ve got a part of their treatment they feel their appointments are not wasted because they can come when there is something specific to achieve in the appointment and they also feel as if they have the information and the knowledge and the permission as it were to do things on their own and its all OK to do that, you know, some of them have done it anyway, but to make it all official if you like, it does give them proper power, whereas sometimes they come and sort of say ‘well I did take some Prednisolone last week’ and you say ‘that's fine, that's fine’ you know, whereas this is actually saying you do take this rather than saying you know you're quite naughty if they have done. [ID 5] | |

| Perceived outcomes for patients | Increased confidence to self-manage |

| It seemed to have fulfilled what they were expecting or what they would have liked to have happened and now it's been formalized, they're very pleased. It's helped them to ask more questions because they're more informed, and they've also got a contact number which reassures them, even though they used to have one in our old clinic anyway but I think now it's written down, you know this is who you contact and this is the number you ring gives them a lot of confidence. [ID 2] |

Theme . | Quote . |

|---|---|

| Adequacy of training for purposes of study | Training adequate |

| The training was fine, except that I realized that when I got down to a clinic you know, there are all sorts of pressures on you that tend to make you a little bit more pragmatic. [ID 5] | |

| Patient-centred aspect of training | Already patient-centred |

| I found it odd and a little offensive that the trainers assumed we needed reminding about patient-centred care and patient choice. Otherwise it was perfectly adequate. [ID 7] | |

| Resulting changes in consultation behaviour | Improved communication |

| So I was happy with the book—I was happy with the dialogue but I had very few comments from those that did come back, because the plan that we had agreed which was clearly written in the book. [ID 12] | |

| Clarifying patient's responsibilities | |

| I think the advantages are the ones that we‘ve alluded to, you know, the sense that the patients feel as if they’ve got a part of their treatment they feel their appointments are not wasted because they can come when there is something specific to achieve in the appointment and they also feel as if they have the information and the knowledge and the permission as it were to do things on their own and its all OK to do that, you know, some of them have done it anyway, but to make it all official if you like, it does give them proper power, whereas sometimes they come and sort of say ‘well I did take some Prednisolone last week’ and you say ‘that's fine, that's fine’ you know, whereas this is actually saying you do take this rather than saying you know you're quite naughty if they have done. [ID 5] | |

| Perceived outcomes for patients | Increased confidence to self-manage |

| It seemed to have fulfilled what they were expecting or what they would have liked to have happened and now it's been formalized, they're very pleased. It's helped them to ask more questions because they're more informed, and they've also got a contact number which reassures them, even though they used to have one in our old clinic anyway but I think now it's written down, you know this is who you contact and this is the number you ring gives them a lot of confidence. [ID 2] |

In most cases, it was felt that the nature of the consultation had not changed dramatically; however, the process was nonetheless viewed as reassuring to patients. The consultants' expectations were that patients would be enabled to take on the responsibility of managing their condition and that the approach would suit the majority of patients.

All consultants believed that patients needed guidance on medical treatment. They did not find that patients disputed their judgements about which drugs were most appropriate. A few consultants felt the assumption that establishing a management plan would form part of a mutual discussion in all cases was false as some patients lacked experience or knowledge and others wanted directive advice from the doctor.

Whilst some consultants reported attempts to incorporate patients' ideas into the management plans there were, however, degrees of acceptance of patients' opinions. It was easy for consultants to accept patients' attempts to change and control aspects of their diet, for example. Most consultants felt that for most patients it was relatively easy to establish a management plan. Writing a mutually acceptable plan was straightforward for stereotypical patients who had a history of successful treatment of relapses with standard drugs—there was a formula to be followed which was easy to explain and which the patient was able to take on board, especially as it was written down. There were problems establishing a plan where the disease was complicated—more likely in Crohn's disease patients. The plan then had to develop into a strategy which was harder to write down.

Actually writing a plan was a change in practice and most consultants agreed this was beneficial to patients. Participating in the training made some consultants realize or confront the problem that patients often had their own interpretation of what constituted a relapse which differed from the medical view. There had been lack of clarity in the past and there were comments that in some cases a certain amount of discussion was needed to change patients' views on what type of relapse warranted treatment. Consultants felt that patients needed clear direction on when they should seek advice because a relapse was not responding to treatment.

Patients were also interviewed to establish the effects of the intervention and Table III summarizes the findings. Patients did not notice any major changes in the attitudes of their consultants; the majority reported having had a good relationship prior to the study. However, being in the study increased expectations that they would be able to discuss several issues about lifestyle self-management with their consultant and in many cases these expectations were not met, as there was no evidence from the interviews that guided self-management plans negotiated with their consultants focused on anything other than medication regimes for relapses, indicating the consultations were not fully patient-centred. Patients were able and willing to take on the responsibility of self-management and appreciated the increased clarity the negotiation of a written plan brought. The consultation seemed in some instances to make patients feel ‘special’ and reinforced their confidence to self-manage.

Summary of patients' views on patient-centred aspects of the intervention

Theme . | Quote . |

|---|---|

| Patient-centredness of consultant | Satisfied with support and attitude of consultant |

| With my consultant you can talk to him—I feel I can talk to him and he listens and explains things and if he doesn't agree with you he'll tell you so you know. You can talk to him and feel confident with him and comfortable. [1107, female, ulcerative colitis] | |

| Time constraints limit effectiveness | |

| I was only about 5 minutes and I wasn't particularly sure what I was doing when I left. It's always so swift when you see him, no matter what time—they seem to be permanently over-booked. [1432: female, Crohn's disease] | |

| Change in provision of care | Increased patient responsibility |

| It's much better for me because I didn't like it when somebody else was controlling it and mostly it was just a waste of time—but when he said I could control my visits myself I said ‘if I’m really bad you'll see me'. I mean I'm reasonable and I won't pester them because they've got other people that's worse than me. [1404: male, ulcerative colitis] | |

| Personal change in behaviour/self-management | Increased self-management |

| Oh yes, he talked about self-management, wrote down in the book, what to do if I have a flare-up, a dosage to take of Prednisolone, so many milligrams a day and reduce gradually and so on and a phone number if I need. I know exactly what a flare-up is, I know when I'm feeling bad and I know physically and emotionally and I take steps as soon as possible. [218: male, ulcerative colitis] |

Theme . | Quote . |

|---|---|

| Patient-centredness of consultant | Satisfied with support and attitude of consultant |

| With my consultant you can talk to him—I feel I can talk to him and he listens and explains things and if he doesn't agree with you he'll tell you so you know. You can talk to him and feel confident with him and comfortable. [1107, female, ulcerative colitis] | |

| Time constraints limit effectiveness | |

| I was only about 5 minutes and I wasn't particularly sure what I was doing when I left. It's always so swift when you see him, no matter what time—they seem to be permanently over-booked. [1432: female, Crohn's disease] | |

| Change in provision of care | Increased patient responsibility |

| It's much better for me because I didn't like it when somebody else was controlling it and mostly it was just a waste of time—but when he said I could control my visits myself I said ‘if I’m really bad you'll see me'. I mean I'm reasonable and I won't pester them because they've got other people that's worse than me. [1404: male, ulcerative colitis] | |

| Personal change in behaviour/self-management | Increased self-management |

| Oh yes, he talked about self-management, wrote down in the book, what to do if I have a flare-up, a dosage to take of Prednisolone, so many milligrams a day and reduce gradually and so on and a phone number if I need. I know exactly what a flare-up is, I know when I'm feeling bad and I know physically and emotionally and I take steps as soon as possible. [218: male, ulcerative colitis] |

Summary of patients' views on patient-centred aspects of the intervention

Theme . | Quote . |

|---|---|

| Patient-centredness of consultant | Satisfied with support and attitude of consultant |

| With my consultant you can talk to him—I feel I can talk to him and he listens and explains things and if he doesn't agree with you he'll tell you so you know. You can talk to him and feel confident with him and comfortable. [1107, female, ulcerative colitis] | |

| Time constraints limit effectiveness | |

| I was only about 5 minutes and I wasn't particularly sure what I was doing when I left. It's always so swift when you see him, no matter what time—they seem to be permanently over-booked. [1432: female, Crohn's disease] | |

| Change in provision of care | Increased patient responsibility |

| It's much better for me because I didn't like it when somebody else was controlling it and mostly it was just a waste of time—but when he said I could control my visits myself I said ‘if I’m really bad you'll see me'. I mean I'm reasonable and I won't pester them because they've got other people that's worse than me. [1404: male, ulcerative colitis] | |

| Personal change in behaviour/self-management | Increased self-management |

| Oh yes, he talked about self-management, wrote down in the book, what to do if I have a flare-up, a dosage to take of Prednisolone, so many milligrams a day and reduce gradually and so on and a phone number if I need. I know exactly what a flare-up is, I know when I'm feeling bad and I know physically and emotionally and I take steps as soon as possible. [218: male, ulcerative colitis] |

Theme . | Quote . |

|---|---|

| Patient-centredness of consultant | Satisfied with support and attitude of consultant |

| With my consultant you can talk to him—I feel I can talk to him and he listens and explains things and if he doesn't agree with you he'll tell you so you know. You can talk to him and feel confident with him and comfortable. [1107, female, ulcerative colitis] | |

| Time constraints limit effectiveness | |

| I was only about 5 minutes and I wasn't particularly sure what I was doing when I left. It's always so swift when you see him, no matter what time—they seem to be permanently over-booked. [1432: female, Crohn's disease] | |

| Change in provision of care | Increased patient responsibility |

| It's much better for me because I didn't like it when somebody else was controlling it and mostly it was just a waste of time—but when he said I could control my visits myself I said ‘if I’m really bad you'll see me'. I mean I'm reasonable and I won't pester them because they've got other people that's worse than me. [1404: male, ulcerative colitis] | |

| Personal change in behaviour/self-management | Increased self-management |

| Oh yes, he talked about self-management, wrote down in the book, what to do if I have a flare-up, a dosage to take of Prednisolone, so many milligrams a day and reduce gradually and so on and a phone number if I need. I know exactly what a flare-up is, I know when I'm feeling bad and I know physically and emotionally and I take steps as soon as possible. [218: male, ulcerative colitis] |

Patients who were the most vulnerable to poor communication and lack of patient-centredness were newly diagnosed patients, those who described themselves as shy or unassertive patients who needed the doctor to instigate or encourage dialogue. Dissatisfaction arose for those who felt intimidated or let down emotionally when their disease became active and difficult to control.

Discussion

The results of this study are limited. Although nurses were involved in the training sessions, they were not directly involved in introducing the intervention to patients and so were not interviewed. It is possible that specialist nurses may be the best placed health professionals to promote self-management; however, for the purposes of this trial, it was felt important to avoid too many additional factors and limit the type of health professional giving the intervention to the consultant. Unlike other studies evaluating the effectiveness of communication in the consultation, there was no systematic observation of the way in which consultants undertook the consultation (van den Brink-Muinen et al., 1991). The process of training and implementation of effective communication for health professionals as part of promoting self-management was judged according to reported satisfaction with training, levels of enablement reported by patients immediately after the consultation introducing guided self-management, and comments made about the consultations derived from qualitative interviews with consultants and patients.

The patient-centred training was used as a method to change professional response to enable them to find ways to integrate the patients' perspectives into the consultation (Stewart et al., 2000). As well as a way of viewing health and illness that impacts on a person's general well-being, patient-centeredness has also been conceptualized as an attempt to empower the patient by expanding the patient's contribution to the consultation (May and Mead, 1999). Research on training professionals in patient-centred care has had mixed results. A RCT of patient-centred care in diabetes (Kinmonth et al., 1998) found patients reported better communication with doctors and nurses, and increased satisfaction, but there was evidence that these patients had poorer disease control, implying that focus on disease management had been lost. Nurses became less keen on a patient-centred approach during the trial and had reduced confidence in their ability to deliver it—there were no such effects for GPs (Woodcock et al., 1999). There were considerable perceived time constraints for both nurses and GPs. An education intervention to change the behaviour of physicians had more positive outcomes (Clark et al., 1998)—asthmatic children had fewer symptoms and reduced health care utilization. A qualitative study of health professionals' views on guided self-management plans for asthma concluded that a more patient-centred, patient-negotiated approach is required (Jones et al., 2000).

The findings of our study confirm and highlight the value of training in patient-centred communication and its potential for promoting self-management effects (van-Dulmen and Bensing, 2002) for a specific chronic condition (IBD). The training proved effective in enabling consultants in gastroenterology to establish guided self-management in patients with IBD. The changes for patients were demonstrated by their increased confidence to self-manage (indicated by the patient enablement score and confirmed by the qualitative interviews) without the need to contact services (indicated by the significant reduction in outpatient visits). The additional resources provided by the intervention (a user-friendly guidebook, a jointly written management plan and a contact telephone number) were delivered in an individualized patient-centred way which clarified the responsibilities and range of possible self-management actions. The self-management focus was, however, very medically orientated and some patients were unable to bring non-medication-related issues into the consultation.

Consultants were receptive and open to the idea of patient-centred communication as a means of establishing better relationships with patients and in promoting greater confidence in the management of their chronic condition. All participants remained fully signed up to the trial. The specialists were enthusiastic about the ethos behind the research and the training, and were prepared to take part in the role-play. It is unusual to introduce this type of training to a senior group of consultants. However, there was a gap between the apparent success of imparting the principles of better communication as a means of encouraging self-management actions in training and their implementation in practice. Consultants were pressurized into adopting a pragmatic approach as they were often constrained by the limited time available during outpatient clinics and thus did not always undertake a fully patient-centred consultation (Rogers et al., 2005). The aspects of the training of most value to the consultants were the discussions with peers, and the opportunity to participate in the evaluation of an approach they considered to be good practice and the way forward for care of patients with chronic conditions. The research highlighted the need for future educational strategies to focus on ways of incorporating and legitimizing aspects of self-management which are of importance to patients, but which are not wholly acknowledged by medical practitioners.

Conclusion

This research has demonstrated that specialists are willing to be trained in patient-centred communication as part of an intervention to establish guided self-management in patients with chronic IBD and that such training is effective; quantitative findings show reduction in the number of outpatient appointments and improvement in perceived coping abilities (enablement score); qualitative interviews showed that both patients and consultants found the approach improved the clarity of communication, and gave patients the confidence and resources to self-manage. More widespread use of this approach in chronic disease management within health service systems is appropriate, and further work needs to be done to explore models for training health professionals in methods to promote and support self-care.

This study was funded by the Health Technology Assessment Programme of the UK NHS. Other members of the trial team include: Elizabeth Nelson, David Reeves, Gerry Richardson, Chris Roberts, Andrew Robinson, Mark Sculpher and David Thompson.

References

Baker, R. (

Bandura, A. (

Benbassat, J., Pilpel, D. and Tidhar, M. (

Clark, N.M. and Gong, M. (

Clark, N.M., Gong, M., Schork, M.A., Evans, D., Roloff, D., Hurwitz, M., Maiman, L.A. and Mellins, R. (

Coulter, A. (

Day, J.L. (

Department of Health (

Dixon-Woods, M. (

Doherty, Y., Hall, D., James, P.T., Roberts, S.H. and Simpson, J. (

Gask, L. (

Guadagnoli, E. and Ward, P. (

Holman, H.R. and Lorig, K. (

Howie, J.G.R., Heaney, D.J., Maxwell, M., Walker, J.J., Freeman, G.K. and Rai, H. (

Janz, N.K. and Becker, M.H. (

Jones, A., Pill, R. and Adams, S. (

Kennedy, A., Robinson, A. and Gask, L. (

Kennedy, A. and Rogers, A. (

Kennedy, A.P. and Rogers, A. (

Kennedy, A.P., Nelson, E., Reeves, D., Richardson, G., Robinson, A., Rogers, A., Sculpher, M. and Thompson, D.G. (

Kinmonth, A.L., Woodcock, A., Griffin, S., Spiegal, N. and Campbell, M.J. (

Margalit, A.P., Glick, S.M., Benbassat, J. and Cohen, A. (

May, C. and Mead, N. (

Mead, N. and Bower, P. (

Osman, L. (

Prochaska, J.O. and Velicer, W.F. (

Robinson, A., Wilkin, D., Thompson, D.G. and Roberts, C. (

Rogers, A., Kennedy, A., Nelson, E. and Robinson, A. (

Rogers, A., Kennedy, A., Nelson, E. and Robinson, A. (

Rollnick, S., Kinnersley, P. and Stott, N. (

Stewart, M., Brown, J.B., Weston, W.W., McWhinney, I.R., McWilliam, C.L. and Freeman, T.R. (

Stewart, M., Brown, J.B., Donner, A., McWhinney, I.R., Oates, J., Weston, W.W. and Jordan, J. (

Stocking, B. (

Thorne, S.E. and Paterson, B.L. (

van den Brink-Muinen, A., Verhaak, P., Bensing, J.M., Bahrs, O., Deveugele, M., Gask, L., Mead, N., Leiva-Fernandes, F. and Perez, M. (

van-Dulmen, A.M. and Bensing, J.M. (