Abstract

The risk of ‘hangover’ effects, e.g. residual daytime sleepiness and impairment of psychomotor and cognitive functioning the day after bedtime administration, is one of the main problems associated with the use of hypnotics. However, the severity and duration of these effects varies considerably between hypnotics and is strongly dependent on the dose administered.

This article reviews epidemiological evidence on the effect of hypnotics on patients’ risk for accidents such as traffic accidents, falls and hip fractures (i.e. end-points for residual effects). Information on the duration and severity of residual effects of 11 hypnotics (flunitrazepam, flurazepam, loprazolam, lormetazepam, midazolam, nitrazepam, temazepam, triazolam, zaleplon, zolpidem and zopiclone) was derived from expert ratings, a meta-analysis and actual driving studies. Epidemiological studies show that the risks of an accident increase with increasing half-life of the hypnotic, but that the use of hypnotics with a short half-life, such as triazolam, zopiclone and zolpidem, can also be associated with increased risks. A summary of results from experimental studies should enable prescribing clinicians to compare residual effects of the various hypnotics at different doses and select the one considered most favourable in this respect for the individual patient. This information should also enable them to inform patients more adequately about the likelihood and duration of residual effects of a specific hypnotic dose.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barbone F, McMahon AD, Davey PG, et al. Association of road-traffic accidents with benzodiazepine use. Lancet 1998; 352(9137): 1331–6

Neutel CI. Risk of traffic accident injury after a prescription for a benzodiazepine. Ann Epidemiol 1995; 5(3): 239–44

Neutel I. Benzodiazepine-related traffic accidents in young and elderly drivers. Hum Psychopharmacol 1998; 13Suppl. 2: S115–23

Cumming RG, Klineberg RJ. Psychotropics, thiazide diuretics and hip fractures in the elderly. Med J Aust 1993; 158: 414–7

Herings RMC, Stricker BH, De Boer A, et al. Benzodiazepines and the risk of falling leading to femur fractures: dosage more mportant than half-life. Arch Intern Med 1995; 155: 1801–7

Lichtenstein MJ, Griffin MR, Cornell JE, et al. Risk factors for hip fractures occurring in the hospital. Am J Epidemiol 1994; 140(9): 830–8

Neutel CI, Downey W, Senet D. Medical events after a prescription for a benzodiazepine. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1995; 4: 63–73

Maxwell CJ, Neutel CI, Hirdes JP. A prospective study of falls after benzodiazepine use: a comparison between new and repeat use. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1997; 6: 27–35

Ray WA, Griffin MR, Schaffner W, et al. Psychotropic drug use and the risk of hip fracture. N Engl J Med 1987; 316(7): 363–9

Ray WA, Griffin MR, Downey W. Benzodiazepines of long and short elimination half-life and the risk of hip fracture. JAMA 1989; 262(23): 3303–7

ICADTS. Guidelines on experimental studies undertaken to determine a medicinal drug’s effect on driving or skills related to driving. Koeln: Bundes Anstalt fuer Strassenwesen (BASt), 1999 Jun

Vermeeren A, De Gier JJ, O’Hanlon JF. Methodological guidelines for experimental research on medicinal drugs affecting riving performance: an international expert survey. Maastricht: Institute for Human Psychopharmacology, 1993. Report No.: IHP 93-127

Wolschrijn H, De Gier JJ, De Smet PAGM. Drugs and driving new categorization system for medicinal drugs. Maastricht: Institute for Drugs, Safety and Behavior, 1991. Report No.: IGVG 91-124

Berghaus G. Arzneimittel und Fahrtuechtigkeit: Metaanalyse experimenteller Studien. Bergisch Gladbach: Bundesanstalt fuer Strassenwesen, 1998. Report No.: FP 2.9108

O’Hanlon JF, Haak TW, Blaauw GJ, et al. Diazepam impairs lateral position control in highway driving. Science 1982; 217(4554): 79–81

O’Hanlon JF. Driving performance under the influence of drugs: rationale for, and application of, a new test. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1984; 18Suppl. 1: 121s–9

Patat A, Paty I, Hindmarch I. Pharmacodynamic profile of zaleplon, a new non-benzodiazepine hypnotic agent. Hum Psychopharmacol 2001; 16(5): 369–92

Goa KL, Heel RC. Zopiclone: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic efficacy as a hypnotic [update of 1986]. Drugs 1991; 32: 48–65

O’Hanlon JF. Zopiclone’s residual effects on psychomotor and information processing skills involved in complex tasks such as car driving: a critical review. Eur Psychiatry 1995; 10Suppl. 3: 137s–43

Nicholson AN. Residual sequelae of zopiclone. Rev Contemp Pharmacother 1998; 9(2): 123–9

Noble S, Langtry HD, Lamb HM. Zopiclone: an update of its pharmacology, clinical efficacy and tolerability in the treatment of insomnia. Drugs 1998; 55(2): 277–302

Langtry HD, Benfield P. Zolpidem: a review of its pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic potential. Drugs 1990; 40(2): 291–313

Rush CR. Behavioral pharmacology of zolpidem relative to benzodiazepines: a review. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 1998; 61(3): 253–69

Johnson LC, Chernik DA. Sedative-hypnotics and human performance. Psychopharmacology 1982; 76: 101–13

Roth T, Roehrs T. Determinants of residual effects of hypnotics. Accid Anal Prev 1985; 17(4): 291–6

Roth T, Roehrs TA. A review of the safety profiles of benzodiazepinehypnotics. J Clin Psychiatry 1991; 52 Suppl.: 38–41

Roth T, Roehrs TA, Stepanski EJ, et al. Hypnotics and behavior.Am J Med 1990; 88(3a): 43s–6

Van Laar MW, Volkerts ER. Driving and benzodiazepine use:evidence that they do not mix. CNS Drugs 1998; 10(5):383–96

Leger D, Guilleminault C, Dreyfus JP, et al. Prevalence ofnsomnia in a survey of 12,778 adults in France. J Sleep Res 2000; 9(1): 35–42

Baiter MB, Manheimer DI, Mellinger GD, et al. A cross-nationalcomparison of anti-anxiety/sedative drug use. Curr Med Res Opin 1984; 8 Suppl. 4: 5–20

Mellinger GD, Balter MB, Uhlenhuth EH. Insomnia and itstreatment: prevalence and correlates. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985; 42(3): 225–32

Pallesen S, Nordhus IH, Nielsen GH, et al. Prevalence ofinsomnia in the adult Norwegian population. Sleep 2001; 24(7): 771–9

Simon GE, VonKorff M. Prevalence, burden, and treatment ofinsomnia in primary care. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154(10):1417–23

Ohayon MM, Roth T. What are the contributing factors forinsomnia in the general population? J Psychosom Res 2001; 51(6): 745–55

Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. I. Sleep 1999; 22Suppl. 2: S347–53

Christer GM, Hublin CGM, Partinen MM. The extent andimpact of insomnia as a public health problem. Primary Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 4 Suppl. 1: 8–12

Reite MD. Treatment of insomnia. In: Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB, editors. Textbook of psychopharmacology. 2nd ed. Washington,DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc., 1998: 997–1014

Benca RM. Consequences of insomnia and its therapies. J Clin Psychiatry 2001; 62 Suppl. 10: 33–8

Bond AJ, Lader MH. Residual effects of hypnotics. Psychopharmacology 1972; 25(2): 117–32

Bond AJ, Lader MH. The residual effects of flurazepam.Psychopharmacology 1973; 32(3): 223–35

Bond AJ, Lader MH. Residual effects of flunitrazepam. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1975; 2(2): 143–50

Borland RG, Nicholson AN. Comparison of the residual effects of two benzodiazepines (nitrazepam and flurazepam hydrochloride) and pentobarbitone sodium on human performance. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1975; 2(1): 9–17

Hindmarch I. A repeated dose comparison of three benzodiazepine derivative (nitrazepam, flurazepam and flunitrazepam) on subjective appraisals of sleep and measures of psychomotor performance the morning following night-time medication.Acta Psychiatr Scand 1977; 56(5): 373–81

Hindmarch I. Effects of hypnotic and sleep-inducing drugs on objective assessments of human psychomotor performanceand subjective appraisals of sleep and early morning behaviour.Br J Clin Pharmacol 1979; 8(1): 43s–6s

Hindmarch I, Clyde CA. The effects of triazolam and nitrazepamon sleep quality, morning vigilance and psychomotorperformance. Arzneimittel Forschung 1980; 30(7): 1163–6

Aranko K, Mattila MJ, Seppala T. Development of toleranceand cross-tolerance to the psychomotor actions of lorazepamand diazepam in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1983; 15(5):545–52

Gillin JC, Spinweber CL, Johnson LC. Rebound insomnia: acritical review. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1989; 9(3): 161–72

Kales A, Soldatos CR, Bixler EO, et al. Rebound insomnia andrebound anxiety: a review. Pharmacology 1983; 26(3): 121–37

Hurst M, Noble S. Zaleplon. CNS Drugs 1999; 11(5): 387–92

Lapeyre-Mestre M, Chastan E, Louis A, et al. Drug consumptionin workers in France: a comparative study at a 10-yearinterval (1996 versus 1986). J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52(5):471–8

Walsh JK, Schweitzer PK. Ten-year trends in the pharmacologicaltreatment of insomnia. Sleep 1999; 22(3): 371–5

Doghramji K. The need for flexibility in dosing of hypnoticagents. Sleep 2000; 23Suppl. 1: s16–20

Kirkwood CK. Management of insomnia. J Am Pharm Assoc 1999; 39(5): 688–96

Ohayon MM, Caulet M. Insomnia and psychotropic drug consumption.Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 1995;19(3): 421–31

Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Guilleminault C. How a general populationperceives its sleep and how this relates to the complaintof insomnia. Sleep 1997; 20(9): 715–23

Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Priest RG, et al. Psychotropic medicationconsumption patterns in the UK general population. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51(3): 273–83

Ohayon MM, Vecchierini MF. Daytime sleepiness and cognitiveimpairment in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med 2002; 162(2): 201–8

Roehrs T, Hollebeek E, Drake C, et al. Substance use forinsomnia in Metropolitan Detroit. J Psychosom Res 2002; 53(1): 571–6

Weyerer S, Dilling H. Prevalence and treatment of insomnia in the community: results from the Upper Bavarian Field Study.Sleep 1991; 14(5): 392–8

Bader G, Ohayon MM. Insomnia in the general population ofSweden. J Sleep Res 2002; 11 Suppl. 1: 10–1

Ohayon MM, Lader MH. Use of psychotropic medication in thegeneral population of France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 63(9): 817–25

Nowell PD, Buysse DJ, Reynolds 3rd CF, et al. Clinical factorscontributing to the differential diagnosis of primary insomniaand insomnia related to mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154(10): 1412–6

Doble A. New insights into the mechanism of action of hypnotics.J Psychopharmacol 1999; 13(4 Suppl. 1): S11–20

Landolt H-P, Gillin JC. GABA-A1a receptors: involvement insleep regulation and potential of selective agonists in thetreatment of insomnia. CNS Drugs 2000; 13(3): 185–99

Moehler H, Fritschy JM, Rudolph U. A new benzodiazepinepharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2002; 300(1): 2–8

McKernan RM, Rosahl TW, Reynolds DS, et al. Sedative butnot anxiolytic properties of benzodiazepines are mediated bythe GABA (A) receptor alphal subtype. Nat Neurosci 2000; 3(6): 587–92

Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Gilman A. Goodman and Gillman’s:the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 10th ed. New York: MacMillan, 2001

Neutel CI, Hirdes JP, Maxwell CJ. New evidence on benzodiazepineuse and falls: the time factor. Age Ageing 1996; 25: 273–8

Herings RMC. Geneesmiddelen als determinant van ongevallen.Utrecht: Universiteit Utrecht, Faculteit Farmacie, 1994

Passaro A, Volpato S, Romagnoni F, et al. Benzodiazepineswith different half-life and falling in a hospitalized population:The GIFA study. Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell’Anziano.J Clin Epidemiol 2000; 53(12): 1222–9

Pierfitte C, Macouillard G, Thicoipe M, et al. Benzodiazepinesand hip fractures in elderly people: case-control study. BMJ 2001; 322(7288): 704–8

Ray WA, Fought RL, Decker MD. Psychoactive drugs and therisk of injurious motor vehicle crashes in elderly drivers. Am JEpidemiol 1992; 136: 873–83

Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in olderpeople: a systematic review and meta-analysis: I. psychotropicdrugs. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999; 47(1): 30–9

Neutel CI, Perry S, Maxwell C. Medication use and risk of falls.Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2002; 11(2): 97–104

De Gier JJ. Review of investigations of prevalence of illicitdrugs in road traffic in diffrent European countries. In: Group P, editor. Road traffic and drugs; 1999. Strasbourg: Council ofEurope, 1999: 13–60

Longo MC, Hunter CE, Lokan RJ, et al. The prevalence ofalcohol, cannabinoids, benzodiazepines and stimulantsamongst injured drivers and their role in driver culpability: parti: the prevalence of drug use in drive the drug-positive group.Accid Anal Prev 2000; 32(5): 613–22

Longo MC, Hunter CE, Lokan RJ, et al. The prevalence ofalcohol, cannabinoids, benzodiazepines and stimulantsamongst injured drivers and their role in driver culpability: partII: the relationship between drug prevalence and drug concentration,and driver culpability. Accid Anal Prev 2000; 32(5):623–32

Honkanen R, Ertama L, Linnoila M, et al. Role of drugs intraffic accidents. BMJ 1980; 281: 1309–12

Skegg DCG, Richards SM, Doll R. Minor tranquilisers and roadaccidents. BMJ 1979; 1(6168): 917–9

Hemmelgarn B, Suissa S, Huang A, et al. Benzodiazepine useand the risk of motor vehicle crash in the elderly. JAMA 1997;278(1): 27–31

Leveille SG, Buchner DM, Koepsell TD, et al. Psychoactivemedications and injurious motor vehicle collisions involvingolder drivers. Epidemiology 1994; 5(6): 591–8

Vermeeren A, Danjou PE, O’Hanlon JF. Residual effects ofevening and middle-of-the-night administration of zaleplon 10and 20mg on memory and actual driving performance. Hum Psychopharmacol 1998; 13 Suppl. 2: S98–107

Vermeeren A, Riedel WJ, Van Boxtel CJ, et al. Differentialresidual effects of zaleplon and zopiclone on actual driving: acomparison with a low dose of alcohol. Sleep 2002; 25(2):224–31

Volkerts ER, O’Hanlon JF. Residu effecten op de actuele rijprestatie:zopiclone versus flunitrazepam en nitrazepam (Residualeffects on real car driving performance: zopiclone versus flunitrazepamand nitrazepam; Dutch with English summary andlegends). J Drug Ther Res 1988; 13: 111–4

Bramness JG, Skurtveit S, Morland J. Zopiklonfunn hos mangebilforere-tegn pa feilbruk og misbruk. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 1999; 119(19): 2820–1

Cumming RG, Le Couteur DG. Benzodiazepines and risk of hipfractures in older people: a review of the evidence. CNS Drugs 2003; 17: 825–37

Tromp AM, Pluijm SM, Smit JH, et al. Fall-risk screening test:a prospective study on predictors for falls in community-dwellingelderly. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54(8): 837–44

Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Benzodiazepines and the risk offalls in nursing home residents. J Am Geriatr Soc 2000; 48(6):682–5

Ray WA, Thapa PB, Gideon P. Misclassification of currentbenzodiazepine exposure by use of single baseline measurementand its effects upon studies of injuries.Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2002; 11(11): 1–7

Mendelson WB. The use of sedative/hypnotic medication andits correlation with falling down in the hospital. Sleep 1996; 19(9): 698–701

Lord SR, Anstey KJ, Williams P, et al. Psychoactive medicationuse, sensori-motor function and falls in older women.Br J Clin Pharmacol 1995; 39(3): 227–34

Cumming RG, Miller JP, Kelsey JL, et al. Medications andmultiple falls in elderly people: the St Louis OASIS Study.Age Ageing 1991; 20: 455–61

Campbell AJ, Borrie MJ, Spears GF. Risk factors for falls in acommunity-based prospective study of people 70 years andolder. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1989; 44(4): 112–7

Granek E, Baker SP, Abbey H, et al. Medications and diagnosesin relation to falls in a long-term care facility. J Am Geriatr Soc 1987; 35(6): 503–11

Wang PS, Bohn RL, Glynn RJ, et al. Zolpidem use and hipfractures in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49(12):1685–90

Sgadari A, Lapane KL, Mor V, et al. Oxidative and nonoxidative benzodiazepines and the risk of femur fracture: the Systematic Assessment of Geriatric Drug Use Via Epidemiology Study Group. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20(2): 234–9

Blake AJ, Morgan K, Bendall MJ, et al. Falls by elderly peopleat home: prevalence and associated factors. Age Ageing 1988;17(6): 365–72

Riedel WJ, Vermeeren A, Van Boxtel MPJ, et al. Mechanismsof drug-induced driving impairment: a dimensional approach.Hum Psychopharmacol 1998; 13Suppl. 2: S49–63

O’Hanlon JF, Ramaekers JG. Antihistamine effects on actualdriving performance in a standard test: a summary of Dutchexperience, 1989–94. Allergy 1995; 50(3): 234–42

O’Hanlon JF, Vermeeren A, Uiterwijk MM, et al. Anxiolytics’effects on the actual driving performance of patients andhealthy volunteers in a standardized test: an integration ofthree studies. Neuropsychobiol 1995; 31(2): 81–8

Louwerens JW, Gloerich ABM, De Vries G, et al. The relationshipbetween drivers’ blood alcohol concentration (BAC) andactual driving performance during high speed travel. In:Noordzij PC, Roszbach R, editors. International congress onalcohol, drugs and traffic safety, T86; 1987. Amsterdam: ExerptaMedica, 1987: 183–6

Borkenstein RF. The role of the drinking driver in traffic accidents,the Grand Rapids study. 2nd ed. Blutalcohol 1974; 11Suppl. 1: 1–131

Vermeeren A, O’Hanlon JF, Declerck AC, et al. Acute effectsof zolpidem and flunitrazepam on sleep, memory and drivingperformance, compared to those of partial sleep deprivationand placebo. Acta Ther 1995; 21: 47–64

Verster JC, Volkerts ER, Schreuder AH, et al. Residual effectsof middle-of-the-night administration of zaleplon and zolpidemon driving ability, memory functions, and psychomotorperformance. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002; 22: 576–83

O’Hanlon JF, Volkerts ER. Hypnotics and actual driving performance.Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 1986; 332: 95–104

Volkerts ER, Van Laar MW, Van Willigenburg AP, et al. Acomparative study of on-the-road and simulated driving performanceafter nocturnal treatment with lormetazepam 1mgand oxazepam 50mg. Hum Psychopharmacol 1992; 7(5):297–309

Brookhuis KA, Volkerts ER, O’Hanlon JF. Repeated dose effectsof lormetazepam and flurazepam upon driving performance.Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1990; 39(1): 83–7

Volkerts ER, O’Hanlon JF. Hypnotics’ residual effects on drivingperformance. In: O’Hanlon JF, De Gier JJ, editors. Drugsand driving. London: Taylor Francis, 1986

O’Hanlon JF. Alcohol and hypnotic hangovers as an influenceon driving performance. Trav Traf Med Int 1983; 1(3): 147–52

Vermeeren A, Ramaekers JG, Van Leeuwen CJ, et al. Residualeffects on actual car driving of evening dosing ofchlorpheniramine 8 and 12mg when use with terfenadine 60mgin the morning. Hum Psychopharmacol 1998; 13Suppl. 2:S79–86

Brookhuis KA, Volkerts ER, O’Hanlon JF. Repeated dose effectsof lormetazepam 1 and 2mg (in soft gelatine capsules)and flurazepam 30mg upon driving performance [Report VK86-18]. Haren: Traffic Research Centre, 1986. Report No.: VK86-18

Riedel WJ, Quasten R, Hausen C, et al. A study comparing thehypnotic efficacies and residual effects on actual driving performanceof midazolam 15mg, triazolam 0.5mg, temazepam20mg and placebo in shiftworkers on night duty. Technicalreport. Maastricht: Institute for Drugs Safety and Behavior,1988. Report No.: IGVG 88-01

Mclnnes GT, Bunting EA, Ings RM, et al. Pharmacokineticsand pharmacodynamics following single and repeated nightlyadministrations of loprazolam, a new benzodiazepine hypnotic.Br J Clin Pharmacol 1985; 19(5): 649–56

Danjou P, Paty I, Fruncillo R, et al. A comparison of theresidual effects of zaleplon and zolpidem following administration5 to 2h before awakening. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1999; 48(3): 367–74

Hindmarch I, Patat A, Stanley N, et al. Residual effects ofzaleplon and zolpidem following middle of the night administrationfive hours to one hour before awakening. Hum Psychopharmacol 2001; 16: 159–67

Troy SM, Lucki I, Unruh MA, et al. Comparison of the effectsof zaleplon, zolpidem, and triazolam on memory, learning, andpsychomotor performance. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000; 20(3): 328–37

Stone BM, Turner C, Mills SL, et al. Sleep in a noisy environment:hypnotic and residual effects of zaleplon [abstract]. JSleep Res 2000; 9 Suppl. 1: 183

O’Hanlon JF. Residual effects on memory and psychomotorperformance of zaleplon and other hypnotic drugs. Prim CareCompanion J Clin Psychiatry 2002; 4 Suppl. 1: 38–44

Darcourt G, Pringuey D, Salliere D, et al. The safety andtolerability of zolpidem: an update. J Psychopharmacol 1999;3(1): 81–93

Lader M, Hindmarch I. Memory, psychomotor and cognitivefunctions after treatment with zolpidem. In: Freeman H, Puech AJ, Roth T, editors. Zolpidem: un update of its pharmacologicalproperties and therapeutic place in management of insomnia.Paris: Elsevier, 1996

Unden M, Roth Schechter B. Next day effects after nighttimetreatment with zolpidem: a review. Eur Psychiatry 1996; 11Suppl. 1: S21–30

Erman MK, Erwin CW, Gengo FM, et al. Comparative efficacyof zolpidem and temazepam in transient insomnia. Hum Psychopharmacol 2001; 16: 169–76

Zammit G. Zaleplon vs zolpidem: differences in next-dayresidual sedation after middle-of-the-night administration [abstract].J Sleep Res 2000; 9Suppl. 1: 214

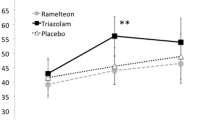

Cluydts R, De Roeck J, Schotte C, et al. Comparative study onthe residual daytime effects of flunitrazepam, triazolam, andplacebo in healthy volunteers. Acta Ther 1986; 12: 205–17

Lobo BL, Greene WL. Insomnia. N Engl J Med 1997; 336(26):1919–20

Mintzer MZ, Frey JM, Yingling JE, et al. Triazolam andzolpidem: a comparison of their psychomotor, cognitive, andsubjective effects in healthy volunteers. Behav Pharmacol1997; 8(6–7): 561–74

Rush CR, Griffiths RR. Zolpidem, triazolam, and temazepam:behavioral and subject-rated effects in normal volunteers. JClin Psychopharmacol 1996; 16(2): 146–57

Moskowitz H, Linnoila M, Roehrs T. Psychomotor performancein chronic insomniacs during 14-day use of flurazepam andmidazolam. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1990; 104Suppl. 4: 44s–55

Jackson JL, Louwerens JW, Cnossen F, et al. Testing the effectsof hypnotics on memory via the telephone: fact or fiction? Psychopharmacology 1993; 111(2): 127–33

Godtlibsen OB, Jerko D, Gordeladze JO, et al. Residual effectof single and repeated doses of midazolam and nitrazepam inrelation to their plasma concentrations. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1986; 29: 595–600

Borbely AA, Mattmann P, Loepfe M. Hypnotic action andresidual effects of a single bedtime dose of temazepam.Arzneimittel Forschung 1984; 34(1): 101–3

Hemmeter U, Muller M, Bischof R, et al. Effect of zopicloneand temazepam on sleep EEG parameters, psychomotor andmemory functions in healthy elderly volunteers. Psychopharmacology 2000; 147(4): 384–96

Hindmarch I. Hypnotics and residual sequalae. In: Nicholson AN, editor. Hypnotics in clinical practice. Edinburgh: MedicinePublishing Foundation, 1982: 7–16

Porcu S, Bellatreccia A, Ferrara M, et al. Performance, abilityto stay awake, and tendency to fall asleep during the night aftera diurnal sleep with temazepam or placebo. Sleep 1997; 20(7):535–41

Warburton DM, Wesnes K. A comparison of temazepam andflurazepam in terms of sleep quality and residual changes inactivation and performance. Arzneimittel Forschung 1984; 34(11): 1601–4

Volkerts ER, Abbink F. Kater-effecten op de rijvaardigheid naslaapmiddelgebruik? Lormetazepam en oxazepam versus placebo(Hangover effects on driving performance following useof hypnotics?). J Drug Ther Res 1990; 15(1): 22–6

Bourin M, Hubert C, Colombel MC, et al. Residual effects oftemazepam versus nitrazepam on memory and vigilance in thenormal subject. Hum Psychopharmacol 1987; 2: 185–9

Laurell H, Tornros J. The carry-over effects of triazolam comparedwith nitrazepam and placebo in acute emergency drivingsituations and in monotonous simulated driving. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol (Copenh) 1986; 58(3): 182–6

Morgan K. Effects of repeated dose nitrazepam andlormetazepam on psychomotor performance in the elderly.Psychopharmacology 1985; 86(1–2): 209–11

Subhan Z, Hindmarch I. Asessing residual effects of benzodiazepineson short term memory. Pharm Med 1984; 1: 27–32

Woods JH, Winger G. Abuse liability of flunitrazepam. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1997; 17(3 Suppl. 2): 1s–57

Carvey PM. Drug action in the central nervous system. NewYork: Oxford University Press, 1998

Roehrs T, Kribbs N, Zorick F, et al. Hypnotic residual effects ofbenzodiazepines with repeated administration. Sleep 1986; 9(2): 309–16

Menzin J, Lang KM, Levy P, et al. A general model of theeffects of sleep medications on the risk and cost of motorvehicle accidents and its application to France. Pharmacoeconomics 2001; 19(1): 69–78

Acknowledgements

The author has provided no information on sources of funding or on conflicts of interest directly relevant to the content of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vermeeren, A. Residual Effects of Hypnotics. CNS Drugs 18, 297–328 (2004). https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200418050-00003